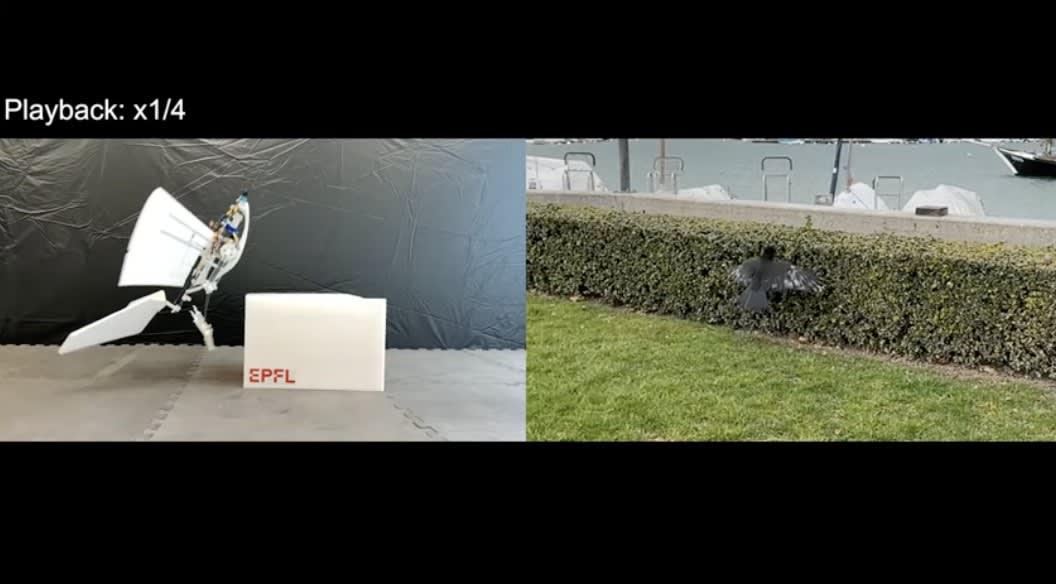

“As the crow flies” is a common idiom referring to the shortest distance between two points, but the Laboratory of Intelligent Systems, led by Dario Floreano, in EPFL’s School of Engineering has taken the phrase literally with RAVEN (Robotic Avian-inspired Vehicle for multiple ENvironments). Designed based on perching birds like ravens and crows that frequently switch between air and land, the multifunctional robotic legs allow it to take off autonomously in environments previously inaccessible to winged drones.

“Birds were the inspiration for airplanes in the first place, and the Wright brothers made this dream come true, but even today’s planes are still quite far from what birds are capable of,” said LIS Ph.D. student Won Dong Shin. “Birds can transition from walking to running to the air and back again, without the aid of a runway or launcher. Engineering platforms for these kinds of movements are still missing in robotics.”

RAVEN’s design is aimed at maximizing gait diversity while minimizing mass. Inspired by the proportions of bird legs (and lengthy observations of crows on EPFL’s campus), Shin designed a set of custom, multifunctional avian legs for a fixed-wing drone. He used a combination of mathematical models, computer simulations, and experimental iterations to achieve an optimal balance between leg complexity and overall drone weight (0.62kg or 1.36 pounds). The resulting leg keeps heavier components close to the ‘body,’ while a combination of springs and motors mimics powerful avian tendons and muscles. Lightweight avian-inspired feet composed of two articulated structures leverage a passive elastic joint that supports diverse postures for walking, hopping, and jumping.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Shin.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing RAVEN?

Shin: One of the biggest challenges was the lack of off-the-shelf solutions for making the leg both powerful and lightweight. Although I was able to obtain the required specifications for the actuation from theoretical calculations, it was difficult to find an off-the-shelf motor and gearbox combination that closely matched the requirements. As a result, I had to design and manufacture the gearbox myself. Additionally, the existing motor control codes were not suitable for my application, so I had to write my own motor control software. These customization processes took up a large portion of the entire developing process.

Tech Briefs: What was the catalyst for this project?

Shin: First of all, I really enjoy watching birds and find them fascinating. Their ability to combine aerial and terrestrial locomotion allows them to access places that humans cannot easily reach. This inspired me to consider the potential of a bird-like robot in various fields, particularly for delivery and search-and-rescue missions. Observing birds closely, I found their jumping take-off to be the most interesting. While conventional fixed-wing vehicles are inspired by birds, they rely on runways or launchers for take-off, unlike birds. I found the idea of eliminating the need for a runway or launcher in fixed-wing vehicles to be a fascinating research challenge.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how RAVEN works?

Shin: RAVEN is a fixed-wing platform with avian-inspired legs that can perform different movements like walking, hopping, and jumping. The legs store elastic energy when crouched, similar to how birds do. When RAVEN jumps, it uses this stored energy to jump faster, giving it the initial speed needed for take-off. After that, RAVEN uses a propeller to fly.

Tech Briefs: What are your next steps?

Shin: Landing with legs could be the next goal. The air-to-ground transition using legs is a relatively underexplored field, and I hope to make advancements in this area. Replacing the fixed wings with foldable wings would be necessary to enable RAVEN to pass through narrow passages. Studying the flapping flight of birds is another area I’d like to explore. Adding flapping wings to a robot like RAVEN would enhance flight agility and provide more opportunities to study bird flight.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Shin: One of the key findings of the paper was that the jumping take-off could be the most energy-efficient strategy when a runway or launcher is not available. I tested three take-off scenarios: jumping take-off, falling take-off, and standing take-off. In the falling and standing take-offs, RAVEN’s legs were fixed, and only the propeller was used.

I initially assumed that the jumping take-off would consume substantially more energy due to the activation of the legs. However, the difference in energy consumption turned out to be smaller than expected, as the falling and standing take-offs took longer to complete.

Additionally, the kinetic energy and potential energy obtained at the moment of take-off were greatest for the jumping take-off (i.e., it achieved the highest take-off speed and height). Therefore, the jumping take-off demonstrated the best energy efficiency, defined as the ratio of kinetic and potential energy to electric energy consumed.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.