Whether it’s the meeting room of an office building, the exhibition room of a museum or the waiting area of a government office, many people gather in such places, and quickly the air becomes thick. This is partly due to the increased humidity. Ventilation systems are commonly used in office and administrative buildings to dehumidify rooms and ensure a comfortable atmosphere. Mechanical dehumidification works reliably, but it costs energy and — depending on the electricity used — has a negative climate impact.

Against this backdrop, a team of researchers from ETH Zurich investigated a new approach to passive dehumidification of indoor spaces. Passive, in this context, means that high humidity is absorbed by walls and ceilings and temporarily stored there. Rather than being released into the environment by a mechanical ventilation system, the moisture is temporarily stored in a hygroscopic, moisture-binding material and later released when the room is ventilated. “Our solution is suitable for high-traffic spaces for which the ventilation systems already in place are insufficient,” said Project Supervisor Guillaume Habert, Professor, Sustainable Construction.

Habert and his research team followed the principle of the circular economy in their search for a suitable hygroscopic material. The starting point is finely ground waste from marble quarries. A binder is needed to turn this powder into moisture-binding wall and ceiling components. This task is performed by a geopolymer, a class of materials consisting of metakaolin (known from porcelain production) and an alkaline solution (potassium silicate and water). The alkaline solution activates the metakaolin and provides a geopolymer binder that binds the marble powder to form a solid building material. The geopolymer binder is comparable to cement but emits less CO2 during its production.

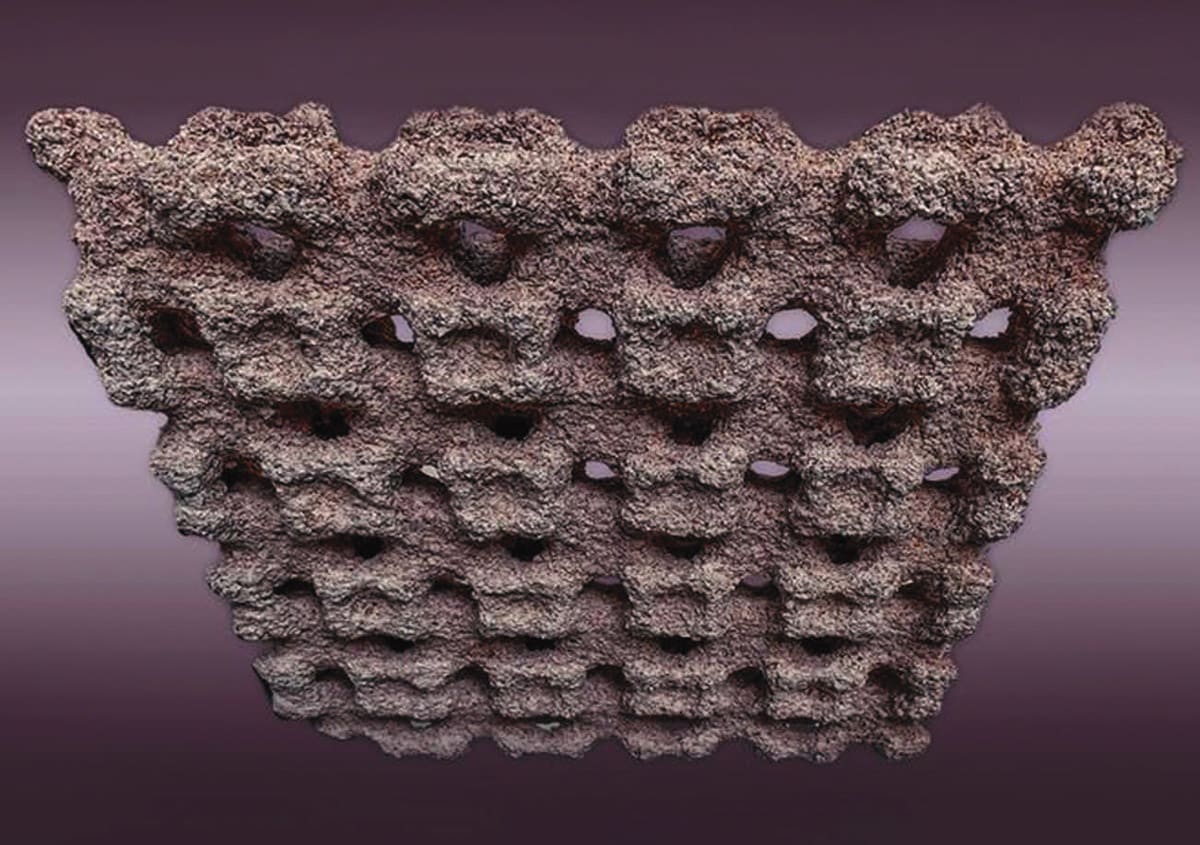

In the ETH project, the scientists succeeded in producing a prototype of a wall and ceiling component measuring 20 × 20 cm and 4 cm thick. Production was carried out using 3D printing in a group led by Benjamin Dillenburger, Professor, Digital Building Technologies. In this process, the marble powder is applied in layers and glued by the geopolymer binder (binder jet printing technology). “This process enables the efficient production of components in a wide variety of shapes,” said Dillenburger.

Combining geopolymer and 3D printing to produce a moisture reservoir is an innovative approach to sustainable construction. Building physicist Magda Posani led the study of the material’s hygroscopic properties at ETH Zurich before recently taking on a professorship at Aalto University in Espoo, Finland. The project is based on the doctoral theses of materials scientist Vera Voney, supervised by Senior Research Associate Coralie Brumaud and architect Pietro Odaglia, who developed the material and the 3D printing machine at ETH.

For more information, contact Marianne Lucien at