We use touch, the dominant user interface for years, to tap keyboards on laptops and tablets, to communicate with our car’s portable GPS, and to text friends and take photos from our smartphones.

Despite the great success of touch, there are other classes of applications for which an untethered user interface is a better choice. With either tiny screens — or no screens at all — wearables are an ideal match for touchless applications. Designers need to know about the enabling qualities of micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) microphone arrays and ultrasonic sensing chips — two products that are ushering in hands-free user interfaces for wearables.

March of the Speech Assistant

Pervasive and excellent speech assistants from Amazon (Alexa), Google (Google Now), and Apple (Siri) have laid a software foundation that good hardware can leverage. Guess Connect is a new Alexa-enabled smartwatch, and other Alexa-based wearables are in development. Google Now is in Android Wear smartwatches and fitness trackers from companies such as LG, Polar, Huawei, and Tag Heuer. Apple uses Siri in its Apple Watch and AirPods, its smart wireless earbuds.

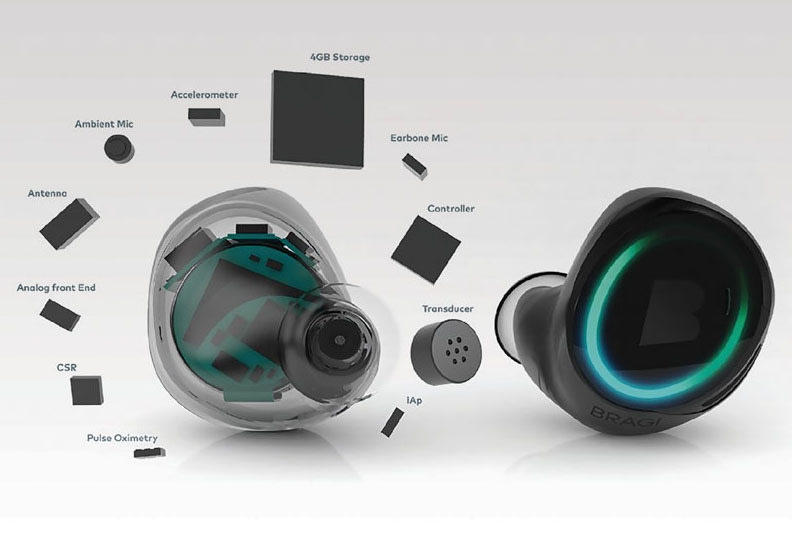

Smaller competitors are offering premium functionality in their earphones. Bolstered by its third-party speech assistant, NeoSpeech, Bragi Dash (see Figure 1) includes buttons for simple functions such as answering phone calls or changing the volume in its smart earphones.

Doppler Labs calls its HearOne earbuds “the world’s first in-ear computing platform.” HearOne supports both Siri and Google Now, allowing Apple and Google fans to continue to use familiar speech assistants.

The common critical component in these wearables and hearables is the MEMS microphone. Because the devices reside at the start of the audio signal chain, improvements in MEMS microphones can have dramatic effects on the voice-assisted user experience — thereby making the audio components a point of differentiation for designers.

Two Microphone Architectures

There are two types of MEMS microphones: capacitive and piezoelectric. Knowles Electronics, the largest supplier of MEMS microphones, released the first capacitive devices in 2000.

Capacitive MEMS microphones operate on the same physical principle as the condenser microphones that have been around for generations. The technologies measure sound with a capacitor, or condenser, made of a flexible diaphragm and a rigid backplate. The diaphragm vibrates in response to sound waves, with bias high enough to create a signal. Capacitive MEMS microphones are by far today’s dominant architecture.

Piezoelectric MEMS microphones, which just reached commercial markets in late 2016, operate upon a different physical principle. Leveraging an energy-harvesting material to generate a signal, piezoelectric MEMS microphones directly convert mechanical sound energy into electrical energy.

In piezoelectric MEMS microphones, the backplate and diaphragm are replaced by a single layer of flexible plates. Changes in sound pressure cause the plates to bend and experience stress. As the plates are built from piezoelectric materials, the stress generates electrical charge, which enables the direct measurement of sound.

Evolving MEMS Microphones

Dedicated to advancing the voice user interface through their respective technologies, capacitive and piezoelectric MEMS microphone suppliers are closely attuned to the migration toward a voice user interface. Many manufacturers see potentially game-changing enhancements in MEMS microphones that will affect wearables and hearables.

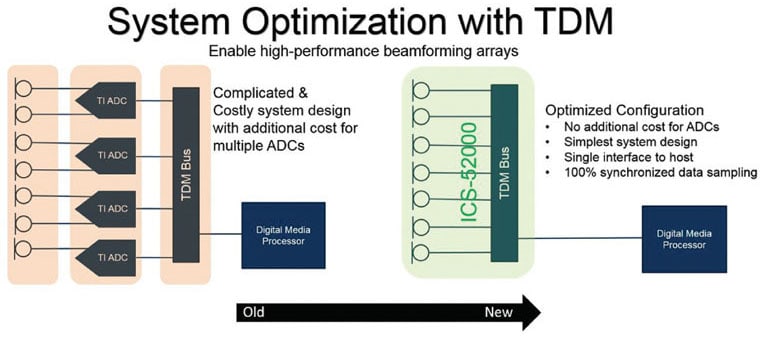

Nicolas Sauvage, senior director of ecosystem at InvenSense, a capacitive MEMS microphone supplier headquartered in San Jose, CA, considers power consumption a top priority, as new technologies require always-on use cases (see Figure 2).

Wake-on-sound capability in some MEMS microphones allows designers to add always-on voice interfaces to any connected device — without increasing power consumption. Through wake-on-sound MEMS microphones, battery-powered devices, such as smart speakers or TV remotes, stay in sleep mode until they are awakened by a noise. The device can then respond to voice commands, freeing users from having to push a button to interact with the device.

“A device is always listening to the user’s voice trigger and commands, rather than having to be close to the device and manually press a button,” said Sauvage.

According to Matt Crowley, CEO of the Boston, MA-based piezoelectric MEMS microphone company Vesper, such a “zero-power” listening functionality will allow batteries to last much longer, extending the battery-recharge time from hours to days or weeks (see Figure 3).

“That’s going to remove a major adoption barrier for hearables and wearables,” said Crowley.

Despite many advancements in software, including voice-to-text transcription, natural language processing, and user identification, however, there is still room for improvement in hardware.

“The quality of the microphone’s signal is still limited by mechanical microphones that are prone to mechanical failure modes — and this is a big issue for arrays,” said Crowley. “The failure of a single microphone can cause an entire array to malfunction.”

Immunity to common failures such as stiction, particle contamination, solder flux contamination, liquid ingress, and breakage lays the foundation for more reliable and robust microphone arrays. Wearables and hearables designers must therefore gravitate towards more rugged microphones.

Ultrasonic Sensing

Designers are additionally using ultrasonic sensing, another interface technology, to complement both touch and voice in applications such as smartwatches and augmented reality (AR)/virtual reality (VR) eyewear.

Ultrasound devices emit high-frequency sound to identify the size, range, and position of an object, moving or stationary. The sensors, then, enable consumer electronics devices to detect motion, depth, and position of objects in three-dimensional space.

Time-of-flight (ToF) measurements are made by emitting a pulse of high-frequency sound and listening for returning echoes. In air, the echo from a target two meters away returns in around 12 milliseconds, a timescale short enough for ultrasound to track fast-moving targets, but long enough to separate multiple echoes without requiring great amounts of processing bandwidth.

Ultrasound offers some significant benefits over optical range-finding solutions such as infrared (IR), time-of-flight (IR ToF), or IR proximity sensors. Ultrasonic sensors are ultra-low power, < 15 microwatts at one range measurement per second, which is 200x below competing IR ToF sensors. The ultrasonic sensors operate in all lighting conditions (including direct sunlight) and provide wide fields of view up to 180 degrees.

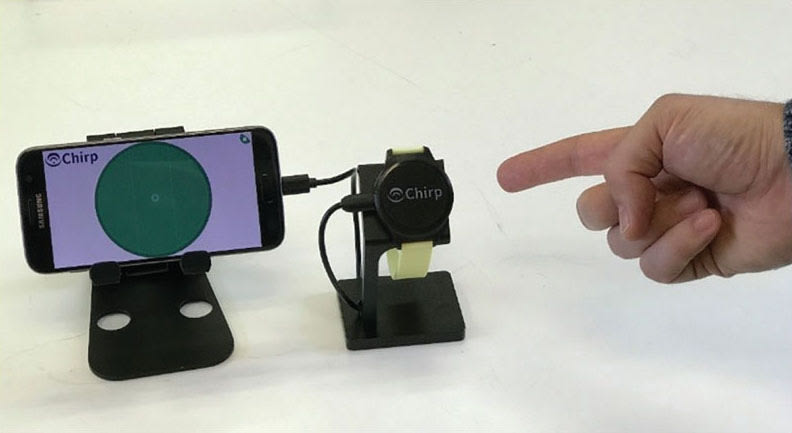

Chirp Microsystems, based in Berkeley, CA, offers high-accuracy ultrasonic sensing development platforms for wearables and for VR/AR. The platform senses tiny “microges-tures,” with 1 mm accuracy, allowing users to interact with smartwatches, fitness trackers, or hearables (see Figure 4). Chirp’s platform allows users to interact with the VR/AR environment without being tethered to a base station or confined to a prescribed space.

David Horsley, CTO at Chirp Microsystems, predicts that gesture and touch will coexist in some products.

“In tablets and laptops, more work is needed on the UI because air-gesture should complement and not replace the touch interface,” Horsley said. “Although introducing a new UI is hard, I think that with the correct UI design, the gesture interface could become universal, in five years or more,” according to the CTO.

Ultrasonic devices potentially protect sensors from being exposed, both visually and physically. With ultrasonic sensing, the designer could conceal a fingerprint button behind the screen itself. Less exposure to clicking on an otherwise overexposed sensor could also more easily enable waterproofing and extend the life of the fingerprint sensor.

Future Markets for Mics

Hearables that add active noise cancellation use six microphones per pair — more than a smartphone. Smart home products such as Amazon Echo and Google Home employ large arrays of microphones to spatially isolate a single speaker in a noisy environment.

The increased use in microphones, according to Crowley, allows hearables to challenge even smartphones and smart speakers, in terms of microphone volume.

“While this is already a healthy market that will continue to grow massively, hearables could still clinch the number one spot because they both interface with smartphones and can function as standalone devices that stream music, source directions, and track our fitness,” said Crowley. “The hearable market is the tip of the AR market, which has huge potential.”

Though the automotive industry’s adoption of new technology has historically been slow, automakers are actively designing in more advanced audio systems, which bodes well for the use of MEMS microphones. Between one and two microphones are featured in today’s cars, but new designs and autonomous vehicles will require 10 to 25 microphones.

Touch user interface technologies will continue to share real estate with voice and gesture technologies for years to come, but the relative allocation of those technologies is shifting. Touch will remain dominant in some applications, including keyboard-driven computing platforms such as laptops and tablets.

Voice, however, is likely to be more pronounced in hearables and smart home products such as smart speakers, and will gain headway in smart appliances and automotive uses. While gesture co-resides with touch and/or voice in many applications, gesture interfaces should become more prevalent in VR/AR applications, as replacements for fingerprint sensors, and in other scenarios for which the swipe of a finger can seamlessly communicate a host of information.

This article was written by Karen Lightman, vice president, SEMI, MEMS & Sensors Industry Group (MSIG). As a resource for linking the MEMS and sensors supply chains to diverse, global markets, MSIG advocates for near-term commercialization of MEMS/sensors-based products through a wide range of activities, including conferences, technical working groups, and industry advocacy. For more information, visit: here .