In just three weeks, the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI) at UC Berkeley built a robotic COVID-19 laboratory.

The "pop-up" system, which has the capacity to handle over 1,000 patient samples a day, will provide desperately needed testing in the Bay Area for those with COVID-19 symptoms and also help public health officials assess the epidemic's spread.

The team behind the development of the technology will begin sampling within the UC Berkeley and City of Berkeley communities this week.

{youtube} https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XzRMcO0Pw6U {/youtube}

Automating the Test for Coronavirus

The basic way to test for a virus is to isolate RNA from a sample, and then amplify it. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) makes millions of RNA copies so that the molecules can be more easily studied.

Fyodor Urnov, the IGI's scientific director for technology and translation, wanted to find a way to automate the PCR process for clinical use.

After a March 13 meeting of 59 people within the institute, Urnov began to mobilize the equipment, people, and money needed for the scaling effort.

UC Berkeley labs possessing high-throughput PCR machines donated their equipment to the cause, while IGI established robotic sample handling.

“We threw our R&D mindset into understanding how we can scale [the PCR processing] up and accelerate it, because we understood this fundamental need of the medical community,” said Urnov, a professor of molecular and cell biology who spent 15 years in the biotech industry before coming to UC Berkeley . “Who we are as scientists really connected to an unmet need.”

The lab will run testing based on a process approved by the Food and Drug Administration, but with more efficiency than the many commercial labs that must still run samples manually, one at a time. The high-throughput machines can test more than 300 samples at once and provide the diagnostic result in less than four hours after receiving patient swabs.

After the emergency modification of state and federal regulations and California’s declared state of emergency, the IGI partnered with clinicians at University Health Services, UC Berkeley’s student health center, and both local and national companies to bring in the necessary robotic and analytical equipment, establish a safe process for sample intake and analysis, obtain the required regulatory biosafety approvals, and train scientists accustomed to conducting fundamental research to analyze patient swabs quickly — with a 24-hour turnaround goal.

In addition to testing, other researchers at UC Berkeley have broken into about a dozen “rapid research response teams” to focus on other COVID-related research projects, including possible improved diagnostics, and new drugs to treat the infection.

"We mobilized a team of talented academic scientists, partnered with experts from companies and pulled together, in a matter of a few days, a group that is operating like a biotech company," said Jennifer Doudna, professor of molecular and cell biology and of chemistry and IGI executive director.

One of the team's talented academic scientists is Abby Stahl, a Postdoctoral Scholar in Doudna's Laboratory.

In a short interview with Tech Briefs below, Stahl explains how the pop-up robotics laboratory works and what other research projects are on the horizon.

Tech Briefs: Can you help me visualize how the pop-up lab works, if I approach the on-campus pop-up lab? What is the sequence of events from arrival to diagnosis?

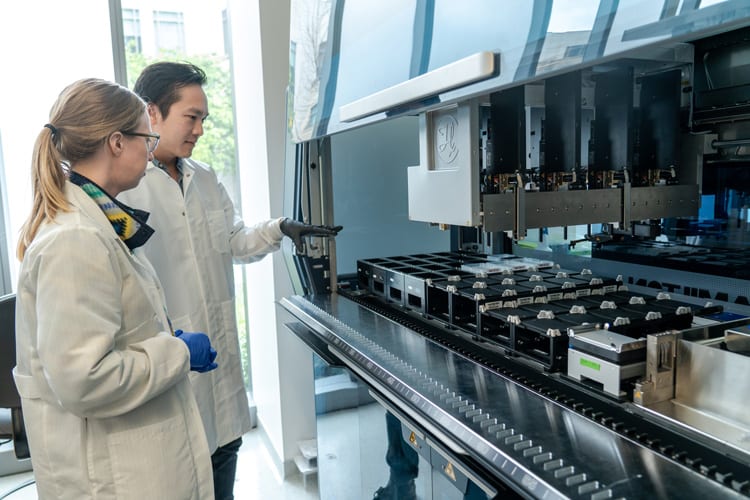

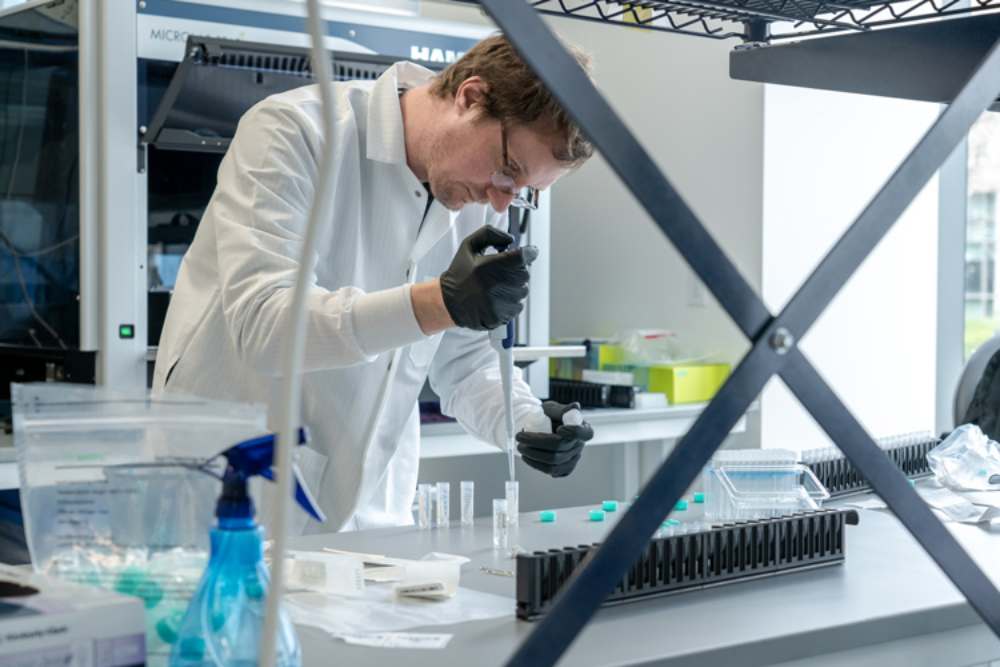

Abby Stahl: Clinical specimens are collected at off-site medical centers. Samples are taken by a swab, stored in a tube containing liquid, and given a unique barcode for tracking. When they arrive at our lab, we store them in 4 ˚C refrigerator until they're ready to be processed. Once ready, we move the samples to a biosafety cabinet. We unpack the tubes, check the barcodes, and disinfect. Then, we uncap and load them into a liquid-handling robot called a Hamilton Starlet . The Starlet scans the barcode and then moves a fraction of the patient sample into new barcoded plate. At this point, we can seal the plates and store them in the fridge again, or keep processing.

Tech Briefs: Is the process automated from here?

Abby Stahl: We currently use a manual pipeline after this, but are gearing up to switch to an automated version. The automated pipeline will use another liquid handling robot called the Hamilton Vantage to extract RNA from the patient samples and transfer them into another type of plate for a process called qRT-PCR. This is done by another device, the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast machine. We look for the presence of three different coronavirus genes. The data are uploaded into a laboratory information management system (LIMS), which interprets the results (and checks positive and negative controls to make sure the process worked properly), and determines whether a patient sample is positive or negative. The output is reviewed by the technical team and then confirmed by a clinical consultant, who forwards the results for reporting back to the physician’s office.

Tech Briefs: Why is robotics especially valuable in responding to a pandemic?

Abby Stahl: The Hamilton Starlet is especially valuable because it increases the efficiency of transferring patient samples into the RNA extraction plates and limits contact time that laboratory technicians have with the sample tubes.

The Hamilton Vantage will increase our testing efficiency from hundreds of samples a day to thousands, because we can run 384 samples per plate instead of 96. While this could be done manually in 384-well plates, it would be very prone to human error when handling such small liquid volumes.

Essentially, robotics let us process samples more reliably and more efficiently.

Tech Briefs: Where has this pop-up lab been used so far? And where do you plan to use this in the near future?

Abby Stahl: This pop-up laboratory was built in the Innovative Genomics Institute at UC Berkeley in approximately three weeks, including achieving CLIA certification and passing FDA validation guidelines that have been extended for emergency use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Volunteers were trained in biosafety and HIPAA and fitted for PPE. Equipment and reagents were rapidly sourced, sometimes purchased by IGI and sometimes generously donated by companies and labs in the area. The laboratory will test patient samples for COVID-19 within the UC Berkeley and City of Berkeley communities starting this week and will continue into the future as needed!

What do you think? Share your questions and comments below.

Transcript

00:00:00 the w-h-o said that the best way to tackle this virus is to test test test this is a call to action that pioneering biochemist jennifer doudna and her colleagues at UC berkeley are working on now as they aim to use their biology labs to test up to 2,000 samples per day about Nicole founder of the gene editing tool CRISPR is using that technology to try to fight covert 19 as she explains

00:00:28 to our Walter Isaacson now and full disclosure of course Walter is currently writing a book on Bowden ur and her work with CRISPR dr. Jennifer Doudna welcome to the show thank you for having me in early March when you watch the spread of the corona virus you suddenly decided it was time for scientists to kick into action so you took your berkeley lab and some of the surrounding

00:00:55 labs and the san francisco area and you mobilize them tell me what you did and why we held a meeting to discuss how the scientists at UC berkeley and our surrounding institutions could get together and address this terrible pandemic and in one thing that emerged from that meeting was that we should find a way to use our resources and our knowledge to test for the virus many of

00:01:20 us agree that one of the most the most important things to be done right now to address the disease is to understand who's infected and how to keep others safe and if you decide you're going to test you do a regular test but you have to get it approved right by the CDC and once you've done that what can you do what 500 a thousand tests per day so it's important to understand we're

00:01:45 academic scientists we don't do clinical testing to do clinical tests with patient samples requires regulatory approval from multiple agencies so we've been on a very fast track to learn first of all what kind of regulate regulation do we need to comply with how do we ensure compliance and how do we get our scientists trained to work safely under these conditions and do it very fast so

00:02:11 we've been fortunate the state of California under its emergency declaration has made it easier to get approval the Food and Drug Administration the federal level has also been very cooperative in helping us to do this and as a result we are really getting very close to being able to do a high throughput test for patient samples at UC Berkeley many other universities

00:02:35 labs are being shut down like with the rest of the university do you think it would be a good idea for universities around the country to get permission to keep their biology labs open and shift them over to this thing of testing so every community could have a high throughput testing center well I would I would first say that you know we're inspired by the University of Washington

00:02:58 many people may be aware that their folks their scientists have been testing patient samples for Meek's and they've played a big role actually in helping to stem the spread of the SARS co2 virus up in the Seattle and larger area in Washington State so we're inspired by this I think it's incredibly important that people be working safely at this time so we're very cognizant of having

00:03:26 to use low density laboratory conditions making sure that our scientists are appropriately protected physically from any potential for infection but yes I mean I think beyond that you know if those conditions can be met and I think having scientists working at this time and contributing their expertise to fight this can Demick is very valuable you've said SARS co2 is that the same as

00:03:53 the kovat 19 and the corona virus we've been talking about yeah let's do a little terminology check so I've had to learn this myself so SARS co2 refers to the actual virus that is causing the current pandemic corona viruses are the family of viruses that's the family of viruses that Tsarskoe to be wan-soo and kovat 19 is the terminology for the disease that this virus poses you'll be

00:04:23 doing the type of tests we've been doing for the couple of months which is just a test for the presence of the virus I've noticed that now in Britain and other places they're starting to do antibody tests can you explain the difference right so the test that we're doing at Berkeley is a test that looks at the virus RNA it's the genetic material that

00:04:47 allows the virus to replicate in upon infection so we're using a test called the polymerase chain reaction that's approved by the World Health Organization and the CDC it's a standard test and importantly it's able to detect the presence of the virus very soon after infection so the difference between that type of a test and what you're asking about a serum

00:05:10 what we call a serological tests that looks for antibodies to the virus is that typically when someone gets exposed to the virus and their body makes antibodies it takes a while for that to happen so it's a it's really a test that looks after the fact has someone been infected by the virus also very useful to know obviously and to figure out who has immunity to the virus but one of the

00:05:32 challenges right now with those types of tests as I've been learning is that the testing materials are not accurate enough to ensure detection of just the Stars co2 virus right now there's a lot of productivity other types of viruses and whereas many many biologists and scientists are working on this problem and they'll probably sort it out but I think that's one of the challenges with

00:05:55 those tests right now it's taking four to six days to get the results of some of these tests would you be able to do it like in a few hours or a day yes so that's that's a primary goal of our lab at Berkeley and the innovative genomics Institute is to be fast so we have brought in high-throughput robotic equipment we've got companies helping us with data management and we hope to be

00:06:21 able to do one to two thousand samples a day as you know I'm writing a book about you and the discovery of CRISPR which is the gene editing technology and CRISPR that technology is based on a trick bacteria figured out over the course of three billion years of how to fight viruses can you explain how CRISPR does that for bacteria sure so CRISPR is a an adaptive immune

00:06:55 system it allows bacteria to detect viruses and protect themselves from future infection and it's a system that you know a handful of scientists were studying and and then a few years ago it was recognized that you know this system which operates as an immune system that we could actually Hermus it as a technology for something quite different which is genome editing and I think it's

00:07:21 a I've been reflecting on this during this pandemic it's a fascinating parallel that bacteria have been dealing with viruses forever they've had to come up with creative ways to fight them and now here we are are humans in a pandemic facing this challenge and so we we often think about you know how can can CRISPR potentially impacts this pandemic in ways that will be beneficial to humans

00:07:48 can CRISPR be used as a detection tool to help us detect the virus in ourselves so this is a really interesting use of CRISPR enzymes that takes advantage of something that my lab discovered about how they work which is that in some cases the enzymes that are able to interact with a piece of nucleic acid which is RNA or DNA and when they do that they turn on an activity a

00:08:18 capability that allows a big amplification of the signal so in other words for every molecule of virus RNA that gets detected we can we can see many many molecules of a reporter a piece of nucleic acid like a little piece of DNA getting cut and so there's a way to do that you use that activity such that there's a big release of a chemical signal that can be seen

00:08:47 visually and so you get you get a the use this CRISPR system to literally detect and then report on its detection of a piece of viral RNA very very quickly so in other word you can engineer it so that if it cuts something that's the virus we're talking about it gloves it sort of has a phosphorescent or some signal does that mean you could have home detection kits that could do

00:09:18 it quickly and anybody could just look at it the way they could a pregnancy test and say I've got it that's the idea absolutely I think that's a very interesting possibility of how this system could ultimately be used are we talking a week a month or a year we're not talking a week we may be talking months we're certainly I think we're I think we're less than a year from that

00:09:43 it's hard to say now we've been talking about detection like how can you test and detect this let's talk about treatments for a second i know that it stanford one of your friends and colleagues stanley key has come up with something he called pac-man which is a way for the actually use a CRISPR based system to actually attack the virus if somebody's sick tell us how that's

00:10:06 progressing yeah so this is another clever idea about how to use CRISPR enzymes to fight the viral infection the idea there is to literally like for those of you that remember pac-man like I do you know literally using enzymes that will go after and cut and destroy only the viral RNA and not RNAs that are present in normal cells and so this is a I think a clever approach it's been

00:10:38 tested in a laboratory setting and there's some you know hope there that that looks like technically it can work I think the challenge is how do you get that into into into a patient how do you get a nurse into infected cells and so if you wanted to get it into an effective cells you'd have to have a delivery mechanism what are the delivery mechanisms well it's very difficult

00:11:01 because in the infection with this virus involved infection in the lung and so we would need to have a way to deliver these CRISPR enzymes into lung cells and that's something that's very hard right now fortunately there's a there's an effort at the innovative genomics to do exactly that for a different purpose namely for

00:11:23 treating cystic fibrosis which is a lung disease that where we think eventually the CRISPR technology could have an impact so the notion that these CRISPR enzymes could cut up and chop away and destroy the Koba 19 virus in somebody's lungs let me ask the same question is that months away years away probably years honestly you know I think we're trying to accelerate the pace of doing

00:11:53 that sort of testing but as you may know that sort of test would require going into human patients and going through phase 1 phase 2 phase 3 clinical trials so this is you know realistically it's yours another thing CRISPR could do in theory would be to edit our own genes and so that ourselves don't have receptors that allow a particular virus to get in is

00:12:19 that a possibility well that's a possibility in the longtime future I would say it's certainly not something that will be I think effective in this particular pandemic one of the challenges to doing taking that approach is that one has to know first of all which receptor to to go after and we do know that for the for the stars to virus but there when when we talk about a

00:12:44 receptor for a virus we're talking about a normal protein that's on the pregnant on the surface of a human cell and as you can imagine that could be problematic to try to remove it it's probably there for a reason so so that's one thing but then then there's also the issue as we just talked about for the the pac-man approach that one has to figure out delivery and how to target

00:13:10 the CRISPR proteins to cells where they could create protective changes and I think that's again something that's going to take years to do we say it will take years didn't we just have a world famous case a year and a half ago where a Chinese scientist ha Joong Ki actually did that for the HIV virus receptor of a cell but he was able to edit the embryos of kids so they no

00:13:36 longer had that receptor and couldn't catch HIV so you say it's a long time away but it's already been done for one receptor right okay well there's a lot of ways to answer that question first of all you know I think the ethics of that study were unfortunately very flawed and that study has been roundly condemned by the international community beyond that I would say that you know doing any kind

00:14:05 of embryo editing is it's just impractical for multiple reasons both technical and ethical and and finally one we need to know in advance which proteins to target in the case of HIV we do know about the receptor proteins for HIV infection but for most viruses or certainly for emerging viruses in the future we can't necessarily predict when you put together a consortium that has

00:14:36 various universities and philanthropies and foundations did you in this case say we're gonna have a slightly different set of rules about to the extent to which we're going to try to profit from or use this in a proprietary way and instead share it yeah actually that's a very active discussion because I think many scientists myself included we don't want to be we have no desire to profit

00:15:06 financially from this we really want to be contributing our expertise and we're not seeking to profit from it we are working with university officials to see if we can put out put out publicly a statement about how intellectual property will be managed for this pandemic how we can make discoveries that are going to come from this large team of people that

00:15:30 are now working on the problem you know openly available so that it can be developed very quickly and I'm optimistic that we're gonna be able to do that quite fast so stay tuned we're hoping to make an announcement about that in the near term dr. Jennifer Doudna thank you for joining us this evening thank you for having me

00:16:00 you