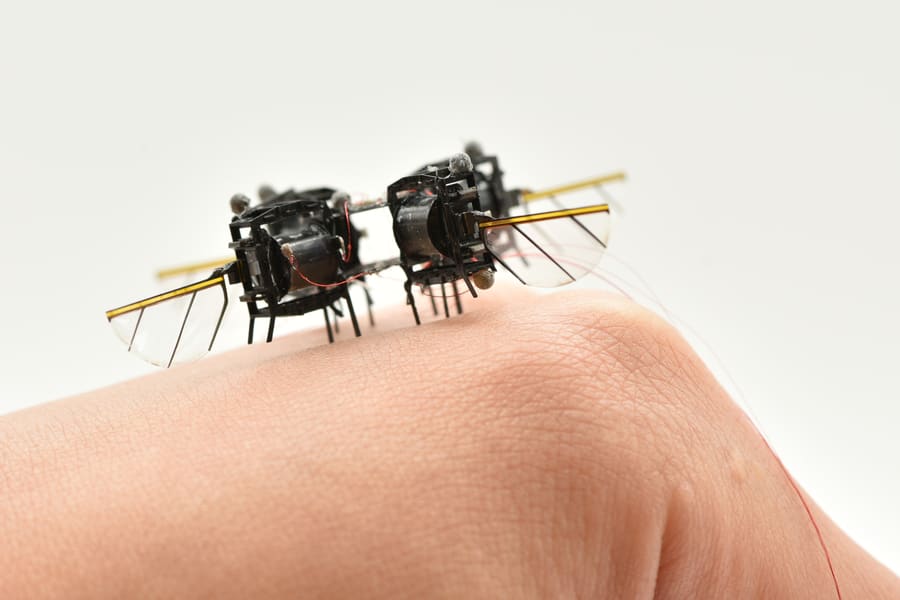

In the future, tiny flying robots could be deployed to aid in the search for survivors trapped beneath the rubble after a devastating earthquake. Like real insects, these robots could fit through tight spaces larger robots can’t reach, while simultaneously dodging stationary obstacles and pieces of falling rubble.

So far, aerial microrobots have only been able to fly slowly along smooth trajectories, far from the swift, agile flight of real insects — until now.

MIT researchers have demonstrated aerial microrobots that can fly with speed and agility that is comparable to their biological counterparts. A collaborative team designed a new AI-based controller for the robotic bug that enabled it to follow gymnastic flight paths, such as executing continuous body flips.

With a two-part control scheme that combines high performance with computational efficiency, the robot’s speed and acceleration increased by about 450 percent and 250 percent, respectively, compared to the researchers’ best previous demonstrations.

The speedy robot was agile enough to complete 10 consecutive somersaults in 11 seconds, even when wind disturbances threatened to push it off course.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Professor Jonathan P. How, the Ford Professor of Engineering in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and Graduate Student Yi-Hsuan (Nemo) Hsiao.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing this AI-based controller?

How: The biggest technical challenge was that existing flight controllers for insect scale robots could not simultaneously meet the need for very high feedback rates and the goal of achieving agile flight under large uncertainties and disturbances. Online optimization methods can, in principle, provide this agility, but only if they can be solved fast enough, which is difficult given the nonlinear dynamics that must be considered at this scale. Our approach was to implement a neural network policy that learns to replicate the behavior of an online planner. This allows the control to run much faster, but only if the neural network can be trained efficiently and with enough robustness to handle real uncertainties. The key innovations that enabled this replication of the planner’s capabilities in the neural network policy were the use of a robust planner based on robust tube model predictive control, the application of new approaches to data augmentation, and the use of behavior cloning. Together, these techniques allowed us to achieve the level of robustness required for reliable agile flight.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how it works please?

How: On the planner side, the process works as follows. The original planner solves an optimization problem to determine the best set of control inputs for the robot over the immediate future, and this can produce the agile maneuvers demonstrated in our experiments. However, solving this problem with the required nonlinear dynamics is computationally expensive and too slow for real time execution. To address this, we first collect a set of offline trials, each consisting of a problem setting (how the robot is currently moving and what we want it to do) and the corresponding solution obtained by solving the optimization problem. The planner provides a robust result in the form of an entire tube of feasible trajectories rather than a single path, giving us a rich dataset with which to train a neural network to imitate this expert behavior. Once trained, the neural network can generate control inputs in real time that closely match those of the original planner for a given scenario, but at a small fraction of the computation time.

Hsiao: Since the advanced control algorithm cannot be run in real time, we trained a neural network to learn the behavior of this algorithm and then execute the neural network in real time.

Tech Briefs: How can onboard sensors help the robots avoid colliding with one another or coordinate navigation?

Hsiao: We are actively pursuing this direction. Our ongoing work integrates onboard sensors and microprocessors directly onto the microrobot, and preliminary results are promising. These efforts are aimed to ultimately eliminating the reliance on external motion-capture systems, enabling more autonomous operation in less structured environments. We hope to share more concrete results in the near future.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Hsiao: This work demonstrates that soft and microrobots, traditionally limited in speed, can now leverage advanced control algorithms to achieve agility approaching that of natural insects and larger robots, opening up new opportunities for multimodal locomotion.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any advice for researchers aiming to bring their ideas to fruition?

Hsiao: This project was made possible by advances in hardware developed through prior work, together with the tight integration of software in this study. More broadly, progress in robotics often comes from looking beyond a single component or discipline. Rather than optimizing hardware or software in isolation, we might benefit from addressing problems through their joint design and integration, where advances in one can enable and amplify progress in the other.