It took over 3,000 pouches of spaceflight food, but Timothy Goulette and Hang Xiao ultimately created a mathematical model that NASA will soon use to ensure that its astronauts are eating well.

After preparing and storing the thousands of packets of spaceflight food according to NASA's specifications, the two UMass Amherst researchers came up with a tool that predicts the degradation of vitamins in spaceflight food over time.

Their model, funded with a $982,685 grant from NASA, will help the agency to more accurately and efficiently schedule resupplying trips.

NASA’s food preparation process requires specific formulation and packaging considerations. To study how the vitamins in the space-food degrade over time, Goulette and his colleagues stored the thousands of meal pouches according to the exact recipes.

"We wanted to mirror NASA's process as closely as possible,” lead author (and food science Ph.D. student) Timothy Goulette told Tech Briefs.

"This enabled us to better understand the true degradation of their spaceflight food items and minimize deviations between what we observed and what NASA should expect to see."

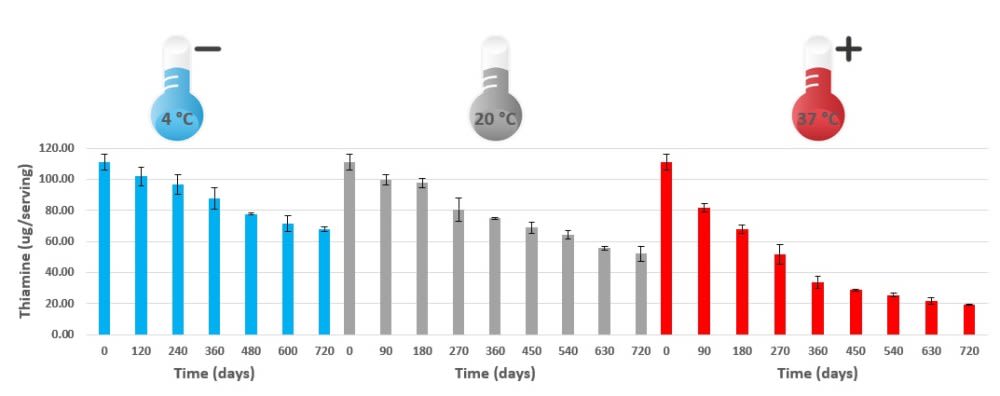

Goulette, Xiao, and colleagues investigated how vitamin B1, also known as thiamine, holds up in three options on NASA’s menu: brown rice, split pea soup, and beef brisket. The team discovered that while the brown rice and split pea soup stored at 20 °C demonstrated resistance to thiamine degradation, the thiamine in beef brisket was much less stable, retaining only 3 percent of the vitamin after two years.

“Proving the model was as simple as comparing these measured values from two years of storage to what was predicted as early as 12 months prior,” said Goulette.

The modeling tool will be especially important as NASA plans for the first human mission to Mars.

"On their longest duration missions, the need to understand the nutritional content of their foods is paramount,” said the lead researcher. “NASA will be able to use a minimal amount of data to quickly and accurately predict the vitamin content of a given food at any given time at a reasonable temperature.”

In an interview with Tech Briefs, Goulette explained just how accurate and precise his team's mathematical model can get.

Tech Briefs: A UMass press release referred to the preparation and storage part of the test process as “painstaking.” How was this part of the process challenging?

Timothy Goulette: We wanted to mirror NASA's process as closely as possible. Their process encompasses specific formulation, processing, packaging, testing, and storage considerations, which necessitated a multi-level analysis on our part to plan and execute this process successfully.

Tech Briefs: Why was making that kind of painstaking effort so important?

Timothy Goulette: This enabled us to better understand the true degradation of their spaceflight food items and minimize deviations between what we observed and what NASA should expect to see.

Tech Briefs: How did this idea for a mathematical model come about? What was NASA’s need?

Timothy Goulette: The model was thought up as a tool that could significantly reduce the time, effort, and cost commitments that are required as part of the conventional approach to determining the loss of nutrients over time. NASA is focused on understanding the nutritional content of the foods that they provide to their crew, and how this nutritional content evolves during a mission. Our model allows them to accurately predict those changes within their foods using a fraction of the data required by the conventional method.

Tech Briefs: What were your most important findings from the mathematical model?

Timothy Goulette: We found that the stability of a given vitamin varies based on the food that it is contained in, and that the effect of temperature on that stability is not always the same among foods. From this, NASA will be able to carefully select meals for the crew which will be the most stable in a given environment. This becomes particularly important if refrigeration is not available on the spacecraft, or the food experiences abuse at high temperatures.

Tech Briefs: What specific foods or “menu options” are most stable?

Timothy Goulette: Our research determined that, when it comes specifically to the stability of thiamine, carbohydrate-rich foods such as split pea soup really shined. Another staple such as brown rice offered similar stability, while fatty, protein-rich options such as our BBQ beef brisket were significantly less conducive to thiamine retention over time.

While not published in this work, we also researched how freeze-drying altered the kinetics of thiamine degradation in our foods compared to non-dried counterparts, using our model.

The goal here was to help NASA determine whether or not adding a freeze-drying process to their food production regime would increase nutrient stability significantly. It's traditionally believed that reducing the moisture content of a food system slows down the degradation within that system. Our findings challenge this presumption in some interesting ways. Hopefully, we can discuss that further when that work is published.

Tech Briefs: Will NASA use this tool? And if/when NASA does, how will astronauts use it, do you think?

Timothy Goulette: NASA plans to use this tool as part of their strategy to routinely provide our astronauts with nutritious food on long-duration missions such as the anticipated manned expedition to Mars. On the ground, NASA will use the model to determine the degradation of essential vitamins in the foods that they send with the crew as well as load on resupply shuttles to support the crew over time (which are prohibitively expensive and need to be carefully and deliberately scheduled).

Functionally, this would look like the following: The Mars-bound shuttle is stocked with enough food, calorically, to last the entirety of the trip to the red planet. However, NASA has preemptively used our model to predict the degradation of vitamins B1 and C in the supplied menu options and found that vitamin C will degrade to an unsafe level months before arrival, and that vitamin B1 overall will only last a few months after touch-down within the foods provided. Knowing this, NASA institutes supplementation, tailored dietary interventions, and schedules resupply missions well in advance of the threat of malnutrition. Alternatively, they may decide to install refrigeration aboard the shuttle in order to slow down the degradation found at ambient temperature in their foods. Our model allows them to estimate the benefit, if any, of this strategy, as a factor in the energy utilization and cost logistics of the mission.

Tech Briefs: How are you able to predict vitamin degradation with “high precision?”

Timothy Goulette: The answer is in our approach to modeling. We are able to accurately predict the loss of a given vitamin within these foods over time because we start with certain reliable assumptions about the kinetics of degradation, and then we use real-life experimental data to tweak these kinetics for each food.

By digging into the literature and establishing a set of axioms for how certain compounds break down, a relationship between degradation rate, temperature, time, and the concentration of that compound can be written. That relationship is then modified given the unique degradation that we observe analytically to produce our predictive model. The beauty of this approach is that this modification requires minimal data, and predictions can be made within a wide range of times and temperatures.

Tech Briefs: What is the model exactly? Is it software? Is it an equation?

Timothy Goulette: The model is a predictive equation for nutrient degradation that we first inform and then visualize using a program that we developed through Wolfram Mathematica.

We start with a set of two rate equations with five unknowns in each: the momentary concentration of a compound at a given time relative to time = 0 (when the concentration is 100%), the time when the concentration is measured relative to t = 0, the storage temperature as a constant, the degradation rate of the compound, and the temperature sensitivity of that compound.

We experimentally set or determine the first three parameters, but the other two need to be determined through solving the two differential equations. The program in Mathematica allows the user to determine the degradation parameters (degradation rate and temperature sensitivity) of their compound of interest visually, by virtue of the fact that only one set of degradation parameters will explain the concentration observed at two different times and two different temperatures.

These parameters are then used to inform the model where predictions can be made mathematically as well as visually.

The degradation rate (k) and temperature sensitivity (c) are already determined. When input into the program, the model is then "informed" and the trajectories are drawn in the bottom module. A solution for k and c is found when those trajectories span through both points in the bottom module, representing the experimentally-determined concentrations following different times and temperatures.

The informed model can then be used to show the degradation trend of the compound at any inputted time and temperature.

Tech Briefs: Why is this modeling tool so important?

Timothy Goulette: As was mentioned, the model that we have developed enables NASA to enhance their knowledge of the stability of the nutrients in food provided to the crew for informed mission and contingency planning with the end goal to optimize crew nutrition and support their success. The tool greatly reduces the time, effort, and cost required to achieve this by the conventional method, and offers NASA superior predictive capabilities.

What do you think? Share your questions and comments below.

Transcript

00:00:01

>> Hi now we're back here inside

the Space Food Laboratory here at the NASA Johnson Space Center and again earlier we've

been talking about some of the preparation and

talking about food and some of the menu items that crew

aboard the International Space Station will be having

this Thanksgiving and again we are here

with Vickie Kloeris, our NASA space scientist, tell

me this is just another area of that food lab so tell

me exactly what area are we in right now.

00:00:27 Okay what you see behind you is our packaging room and so it's really a portable, commercial portable clean room that we've converted into a packaging area so all our packaging equipment is inside. It has Hepa filters that filter the air to help keep the contamination possibilities down when we're packaging food. So the type of food that you would...we do all our beverages would be packaged here like we have in this package and all our freeze dried items as well

00:00:56 as our bite sized products like

M and M's, cookies, crackers, candies all of those items would

be packaged in the equipment that you see here

in this facility.

>> Okay great so tell me a

little about the packaging, what do we have, what

kind of packaging is this?

>> The beverage package,

all of our beverages are in powdered form and so this

is a foil laminate pouch that we buy from a commercial

manufacturer, we buy it, it's sealed on three sides,

it's open on this end. We weigh in the appropriate

amount of powder

00:01:26 for a single serving and

then the packaging equipment that you see here is designed

to seal the beverage adapter or the septum adapter assembly

into the end of the package and so this is what allows

the water to be injected on orbit using the

rehydration station. Inside this is a septum and the

septum is a little plastic valve so the needle inserts and the

water is injected and then when the needle is withdrawn

the septum closes off to prevent the fluid from

flowing out of the package.

>> Okay, great and then they

just take this and shake it up

00:02:01 and then insert a straw...

>> Yeah into the package

and drink through the straw.

>> Okay.

>> And the straw has

a clamp on it so that in between sips they

can clamp it closed to prevent the fluid

from flowing out.

>> The re-hydratable products

all require the addition of some amount of water

prior to consumption, has the same septum

adaptor assembly, in this case they inject the

water, they wait for the product

00:02:25 to absorb the water then they're

able to cut the package open with scissors and eat out of the

package with a fork or a spoon. Typically what they'll do

is cut an X across the top, they'll eat out of the

center of the X and the flaps from the remaining material

will help hold the rest of the product inside the

package while they extract the bite that they're going to eat.

>> Okay.

>> You're depending

on the surface tension of the wet product to cause

it to stick to the package

00:02:50 or stick to your utensil.

>> So there's no turkey carving

up there, it's just the scissors and they cut it open and

eat that just as that is. So talk to me a little bit

about...so this is what he is doing actually right behind

us, there's some packaging now, can you tell me about how long

in advance do we typically start to prepare food that is

going to flown into space?

>> Well, we have to maintain

an inventory of our products at all times and so typically

we'll be producing...we produce like our thermo stabilized

products we'll produce those

00:03:24 year round.

>> Okay.

>> Because it will

take us an entire year to produce all the

different kinds of thermo stabilized

products that we have. Beverages we're going to

package those usually as needed and so typically for a ship set for beverages we'll start

packaging those about four of five months in

advance of the time that shipment is actually

going to go out the door.

00:03:48

>> Okay.

>> And re-hydratables usually

we try to package those in about...within about a six

or eight month period prior to the shipment going

out the door.

>> Okay, great. So this is the packaging

but talk to me a little bit about the packing, how

is this food packed to go up into the International

Space Station.

>> Okay well we have a

couple of different options for actually the containers

that we use to send the food

00:04:11 to orbit, one is a collapsible metal food container, typically we use that when we're sending food on the Progress because the Progress has slots built into it that hold those containers. Another option that we often use is what we call our bulk overwrap bag, it's really just a large plastic bag that we overwrap the contents of one of those metal containers in. And we're typically using that when we're sending food on the ATV or HTV.

00:04:39

>> Okay and these are cargo

ships of the different agencies that we have [inaudible].

>> Unmanned cargo vehicles.

>> Right, Okay.

>> Okay and now with Space X the

new commercial cargo [inaudible] we're also using the

bulk overwrap bags, the plastic overwrap bags

which I can show you later.

>> Sure.

>> And they take those and

actually put them inside of the crew transfer

bag, or the MO2 bags,

00:05:04 the different...we

have an example of one in there in the lab as well.

>> Okay.

>> But they typically take

those bulk overwrap bags and stow them inside another

container to get them to orbit.

>> Great, okay now as you

know we've been answering some questions from people that

we've polled and thanks to our total followers just

sending these questions. Now one of the questions

and this kind of talks about the future space feed

system and so I'd like you

00:05:29 to kind of go on and

talk to me a little about what technologies we're

exploring for space feed system because obviously International

Space Station is one place and then there are further

destinations that's we'd like to go.

>> Right.

>> And we need food to sustain

us for longer periods of time. One of these questions are

given a true space galley, this comes from Todd Templeman, what's the most useful

edible we could grow

00:05:50 in an attached green

house, thanks.

>> Okay so there's two ways

to look at that question, in transit if you were

say on your way to Mars on a six month mission, which

now we know it will take with current propulsion it

will take about six months to get there you could grow

some crops during the transit but typically those would have to be what we call

pick and eat crops. Meaning something like a cherry

tomato that you could grow, you could harvest and

basically all you'd have

00:06:20 to do is clean it and eat it. Because in micro gravity you're not really going to be able to do a lot of the elaborate processing of crops or elaborate cooking because without gravity that gets very, very difficult so it's not really practical to think about growing wheat in micro gravity and then having to mill it into flour, that's not going to work in micro gravity. But when you get to the surface of the moon or Mars and you have and you're on the surface where you have

00:06:50 at least partial gravity you can

certainly then begin to think about the possibility

of either growing crops to help you recycle your air and

water and then also using them as part of your food system or

also the possibility of taking like bulk ingredients

with you say like flour and then doing more

elaborate cooking...

>> So not having our

food already prepared but actually kind of

putting ingredients together to prepare a dish.

>> Actually doing real cooking,

probably you're not going to do

00:07:22 that 100 percent because it does

take a lot more free time and so in that situation it's probably

going to end up being a mix of prepackaged foods and

perhaps stuff that you prepare.

>> Kind of like the

cooking I do at home.

>> Right, exactly.

>> All right...well

thank you that's a wrap on the food wrap here and how

it's wrapped here at NASA, the NASA Space Food Lab,

again with Vickie Kloeris, from our kitchen to

yours, happy Thanksgiving. [ Music ]

00:07:50 [ Silence ]