From sorting objects in a warehouse to navigating furniture while vacuuming, robots today use sensors, software control systems, and moving parts to perform tasks. The harder the task or more complex the environment, the more cumbersome and expensive the electronic components.

Mechanical engineering researchers in the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) think there’s another way to design robots: Programming intended functions directly into a robot’s physical structure, allowing the robot to react to its surroundings without the need for extensive on-board electronics.

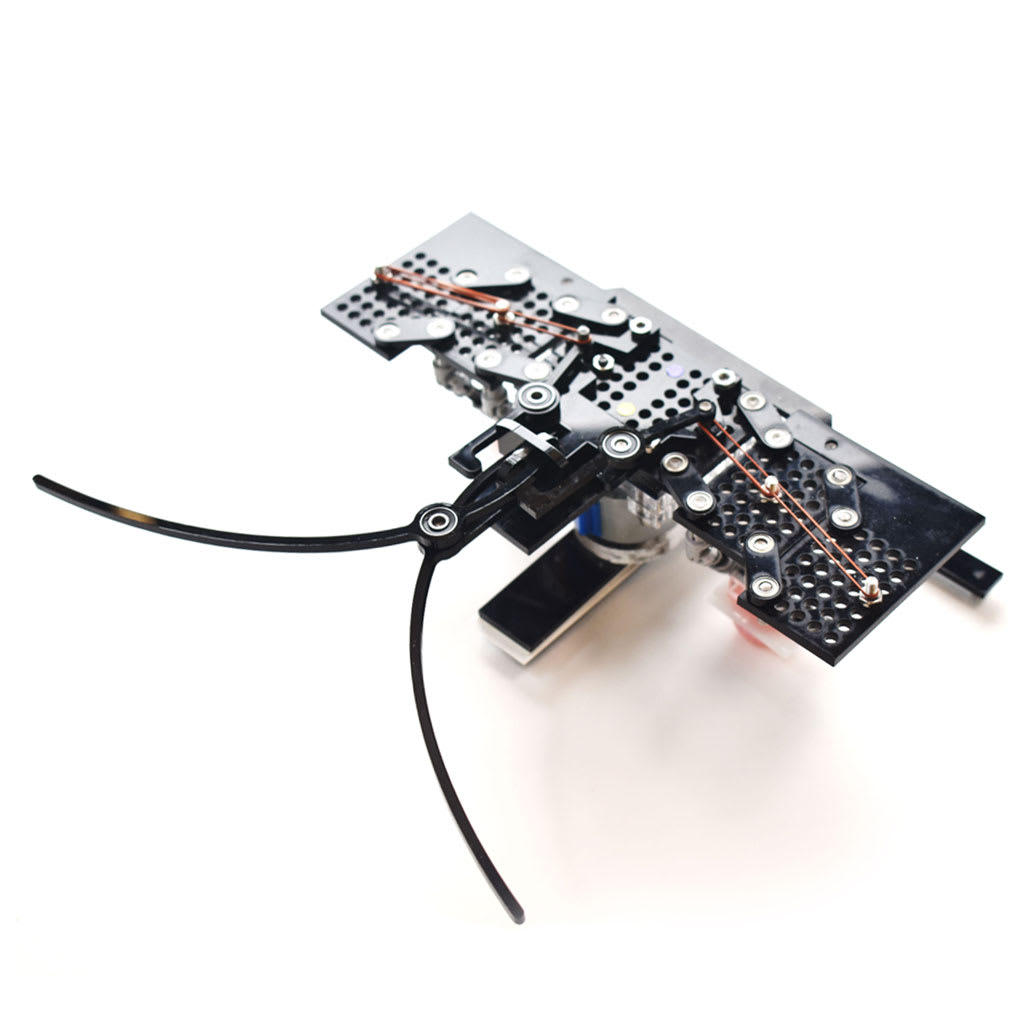

A team from the lab of Katia Bertoldi, the William and Ami Kuan Danoff Professor of Applied Mechanics at SEAS, designed a proof-of-concept walking robot with just four moving parts connected by rubber bands and powered by one motor. With its movements programmed via the placement of the rubber bands, the robot can find its way through mazes and avoid obstacles; its movements change based only on how it is touched or pressed by its environment, with no electronic brain.

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the work was led by Leon Kamp, a graduate student in Bertoldi’s lab whose secondary graduate study is in Critical Media Practice. Trained in engineering and architecture, Kamp turned to robotics as a practical application of his interest in form, material, and mechanics. He wondered if robotic intelligence could be infused into structure using mechanical principles.

Kamp and colleagues built their robotic mechanism from a chain of flat plastic blocks joined by levers and rubber bands. The stretching of the rubber bands assigns a certain energy cost to rotating each lever. The movement of the mechanism can be “programmed” as it follows the order of rotations that has the lowest energy cost. By attaching a leg to this mechanism, they built a robot that can walk forward and backward using one motor for different configurations of rubber bands.

This physical programming allows the robot to passively sense and respond to forces from its environment. It “feels” its surroundings via a pair of antennae attached to the front. When one antenna hits an obstacle, the robot responds and adapts from walking straight to turning away. It can autonomously navigate mazes or move away from obstacles.

In another configuration, the mechanism can be used to automatically sort objects based on their mass. In this case the rubber bands are used to “program,” where objects are picked up and dropped off at different locations for specific targeted masses.

While the mechanism can only accomplish a small number of simple tasks, the concept could be expanded to robots that move faster or jump over obstacles. In the future, robots like this could be made of flexible materials that are lightweight and easy to manufacture. Such designs could lead to autonomous machines that are physically intelligent and rely on fewer electronics or traditional control systems to function.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.