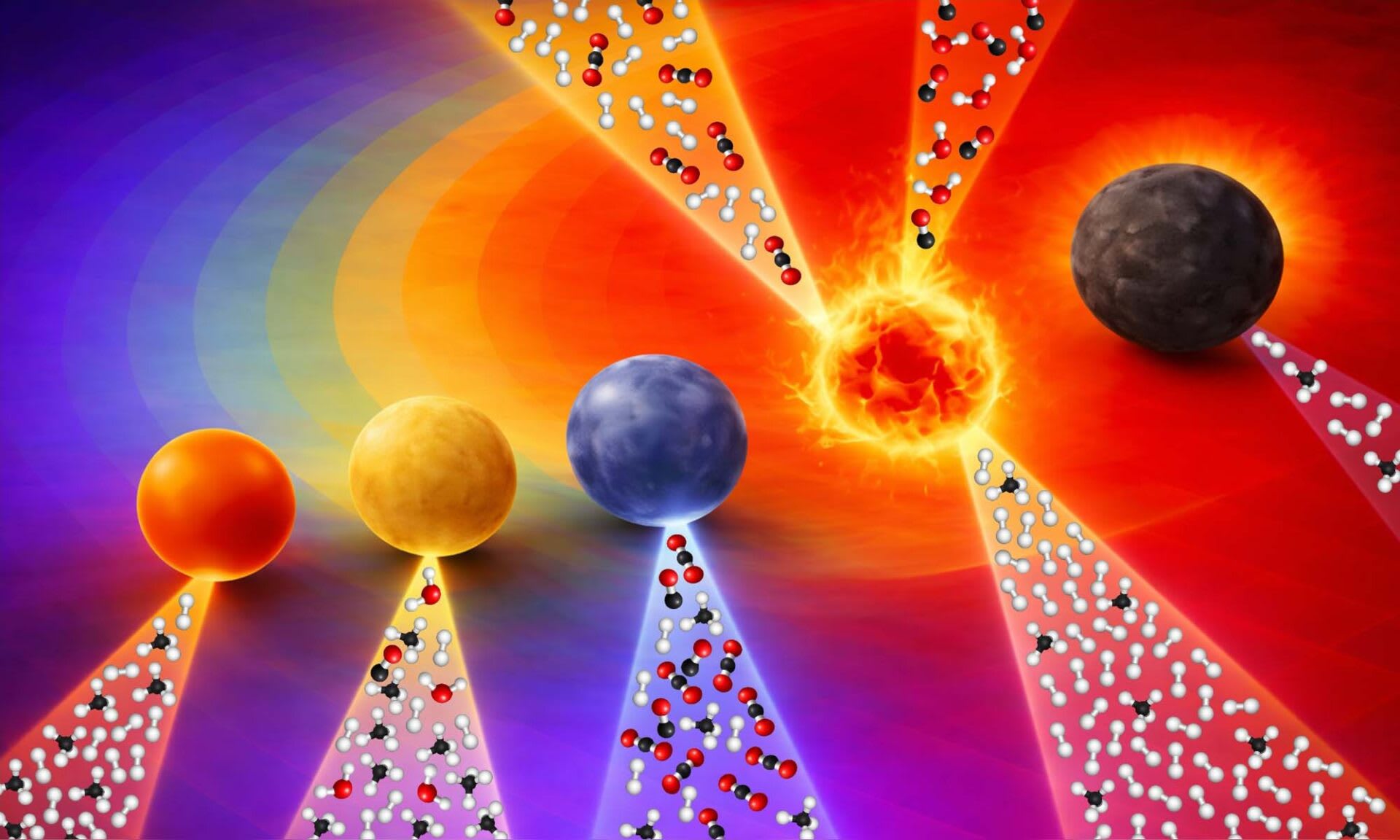

Important everyday products — from plastics to detergents — are made through chemical reactions that mostly use precious metals such as platinum as catalysts. Scientists have been searching for more sustainable, low-cost substitutes for years, and tungsten carbide — an Earth-abundant metal used commonly for industrial machinery, cutting tools, and chisels — is a promising candidate.

But tungsten carbide has properties that have limited its applications. Marc Porosoff, Associate Professor, University of Rochester, Department of Chemical and Sustainability Engineering, and his collaborators recently achieved several key advancements to make tungsten carbide a more viable alternative to platinum in chemical reactions.

Sinhara Perera, a chemical engineering Ph.D. student in Porosoff’s lab, said that part of what makes tungsten carbide a difficult catalyst for producing valuable products is that its atoms can be arranged in many different configurations — known as phases.

“There’s been no clear understanding of the surface structure of tungsten carbide because it’s really difficult to measure the catalytic surface inside the chambers where these chemical reactions take place,” said Perera.

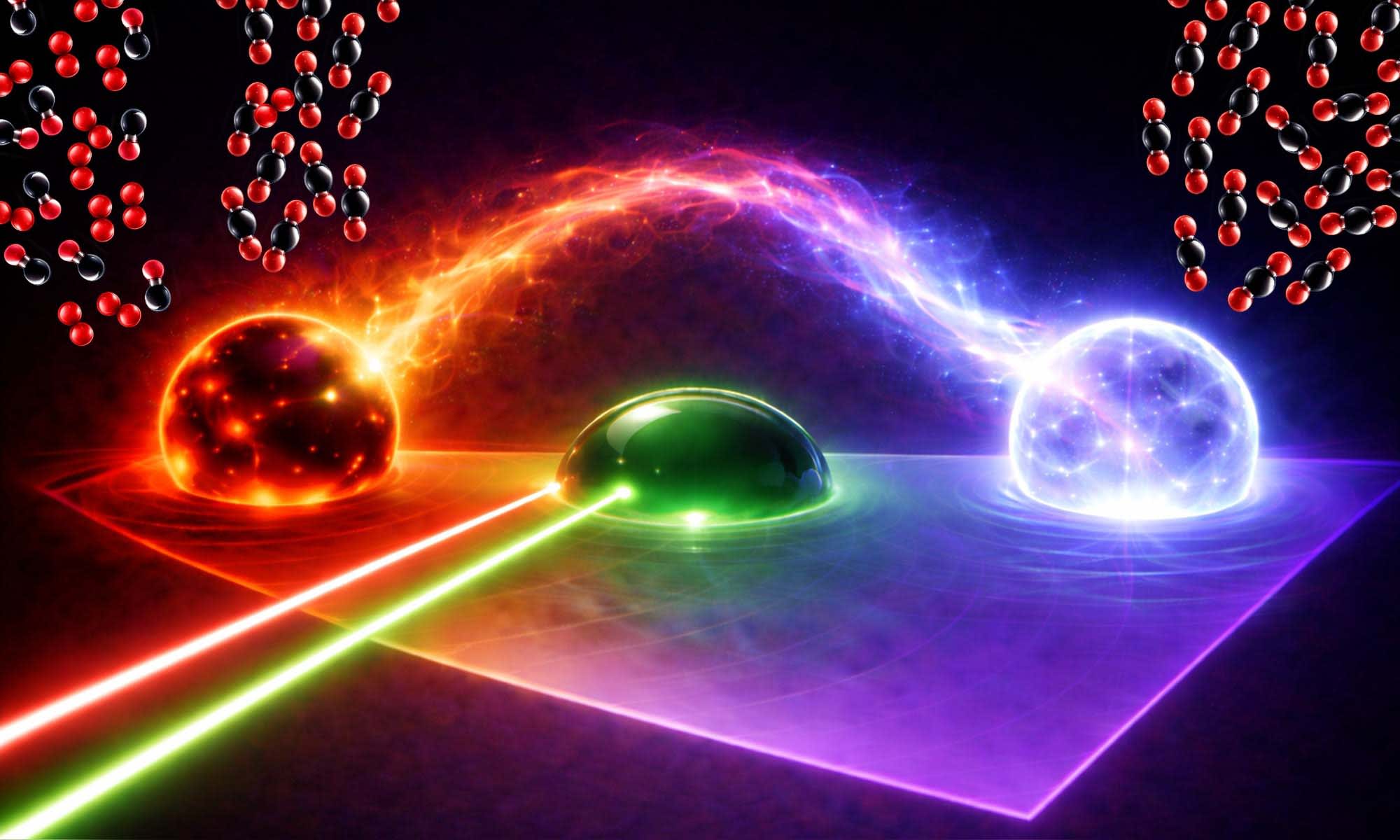

In a study published in ACS Catalysis, Porosoff, Perera, and chemical engineering undergraduate student Eva Ciuffetelli ’27 overcame this problem by very carefully manipulating tungsten carbide particles at the nanoscale level within the chemical reactor — a vessel where temperatures can reach above 700 °C. Using a process called temperature-programmed carburization, they created tungsten carbide catalysts in their desired phase inside the reactor, ran the reaction, and then studied which versions performed the best.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Porosoff.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while performing the temperature-programmed carburization?

Porosoff: There were a couple of issues; they relate to a few different things. The first is that the phase of tungsten carbide that we were targeting is a metastable phase. It's less thermodynamically stable than this hexagonal phase. So, we wanted to target orthorhombic beta W2C, but thermodynamics favors delta WC. That's one challenge.

The next challenge was that these materials are very pyrophoric, and that means they will combust when they're exposed to air. So, a requirement is that we — if we want to do any kind of characterization after we make the material or move it into a reactor — have to do a passivation, which means we do a controlled oxidation with a low concentration of oxygen. That forms this protective oxide layer on the surface of the material.

And the problem is, once you form that protective oxide layer, the material is never the same again. The catalyst is forever different. When we try to do characterization or reactor studies on that passivated material, the things that we are measuring do not reflect the true nature of that material. To alleviate that challenge, we had to come up with a new protocol to do in-situ carbonization, which means we made the material in the reactor where we did these CO2 conversion studies, and then immediately started the reaction without any exposure to air.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms what the temperature program carburization is?

Porosoff: Temperature-programmed carburization means we start with a pre-catalyst, tungsten oxide. Then we have to thermally treat tungsten oxide in the carburization gases to make tungsten carbide. The process involves flowing gaseous carbon precursors, which in this case is methane, along with hydrogen under a temperature ramp. So, the temperature is increasing and follows a specific program while these gases are flowing. In short, it means we're flowing methane and hydrogen while we're changing and increasing the temperature to convert tungsten oxide into tungsten carbide.

Tech Briefs: How can tungsten carbide help with hydrocracking? And can you explain what hydrocracking is?

Porosoff: Hydrocracking is a series of reactions that uses hydrogen to break carbon-carbon bonds. And the reason this is important is because plastics like polyolefins, polyethylene, polypropylene consist of these very long chains of carbon-carbon bonds. So, if we want to take these big plastics — like water bottles, waste plastic — and then reuse or recycle them, we have to be able to break those bonds efficiently. And to break those bonds, you need two functions. You need an acid function, and you need a metallic function.

The tungsten carbide part has that metallic functionality. And then there are also these oxide groups present on the surface — tungsten oxides — that can perform acid functionality. So, those two functions are present within these carbide catalysts.

Tech Briefs: What are your future plans?

Porosoff: We are continuing to investigate the potential of carbide catalyst for various reactions to increase energy efficiency.