Currently there are about 500,000 pieces of human-made debris in space, orbiting our planet at speeds up to 17,500 miles per hour. This debris poses a threat to satellites, space vehicles, and astronauts aboard those vehicles. However, cleaning up the debris is problematic. For example, suction cups don’t work in a vacuum, and traditional sticky substances like tape are largely useless because the chemicals they rely on can’t withstand extreme temperature swings.

To address the problem, researchers from Stanford University and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) combined gecko-inspired adhesives and a custom robotic gripper to create a device for grabbing space debris. They tested their gripper in multiple zero gravity settings, including the International Space Station.

Mark Cutkosky, professor of mechanical engineering, explains that the gripper is “an outgrowth of work we started about 10 years ago on climbing robots that used adhesives inspired by how geckos stick to walls.” The group tested their gripper, and smaller versions, in their lab and in multiple zero-gravity experimental spaces, including the International Space Station (ISS). The results were promising and a likely next step would be use of the grippers outside the station.

“There are many missions that would benefit from this, like rendezvous and docking and orbital debris mitigation,” said Dr. Aaron Parness, group leader of the Extreme Environment Robotics Group at JPL. “We could also eventually develop a climbing robot assistant that could crawl around on the spacecraft, doing repairs, filming, and checking for defects.”

The adhesives developed by the Cutkosky lab have previously been used in climbing robots and even a system that allowed humans to climb up certain surfaces. They were inspired by geckos, which can climb walls because their feet have microscopic flaps that, when in full contact with a surface, create a Van der Waals force between the feet and the surface. These are weak intermolecular forces that result from subtle differences in the positions of electrons on the outsides of molecules.

The flaps of adhesive on the gripper are only sticky if the flaps are pushed in a specific direction, and making it stick only requires a light push in the right direction. This is a helpful feature for the kinds of tasks a space gripper would perform.

“If I came in and tried to push a pressure-sensitive adhesive onto a floating object, it would drift away,” said Dr. Elliot Hawkes, a visiting assistant professor from the University of California, Santa Barbara. “Instead, I can touch the adhesive pads very gently to a floating object, squeeze the pads toward each other so that they’re locked and then I’m able to move the object around.” The pads unlock with the same gentle movement, creating very little force against the object.

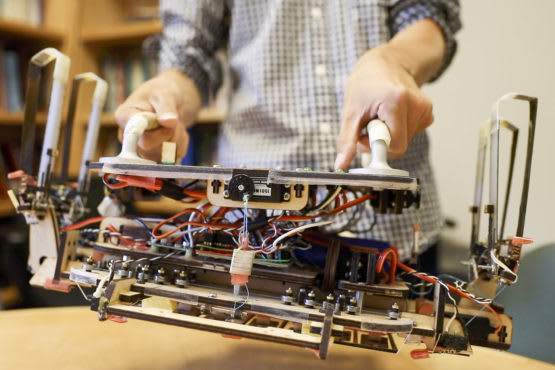

The gripper the researchers created has a grid of adhesive squares on the front and arms with thin adhesive strips that can fold out and move toward the middle of the robot from either side. The grid can stick to flat objects, like a solar panel, and the arms can grab curved objects, like a rocket body.

One of the biggest challenges of the work was to make sure the load on the adhesives was evenly distributed, which the researchers achieved by connecting the small squares through a pulley system that also serves to lock and unlock the pads. Without this system, uneven stress would cause the squares to unstick one by one, until the entire gripper let go. This load-sharing system also allows the gripper to work on surfaces with defects that prevent some of the squares from sticking.

The group first tested the gripper in the Cutkosky lab. They closely measured how much load the gripper could handle, what happened when different forces and torques were applied and how many times it could be stuck and unstuck. Through their partnership with JPL, the researchers also tested the gripper in zero gravity environments and developed a small gripper that went up in the ISS.

Transcript

00:00:00 [MUSIC PLAYING] We have a lot of junk orbiting Earth and it's dangerous. And so people have been looking at different ways to latch onto items in space and possibly retrieve them, maybe even reuse some of them. So what we've developed is a gripper that uses gecko-inspired adhesives. It's a microstructured adhesive. It's much simpler than what the gecko has,

00:00:29 but it works the same way. Most of the time it's not sticky. It has tiny, little microscopic flaps. And it only sticks when you apply a load to it in the direction along the surface. So as you apply a load, each of these flaps lays down like this, and you get very close contact. And it's this close contact that turns on the adhesive. When you release that pulling force, it comes back up with elastic energy

00:00:53 and comes off with almost no force. We aimed at grasping a variety of objects from these solar panels that have big flat surfaces. Some of these rocket bodies that have really curved like cylindrical surfaces. That's why we have two modules. The type of adhesive we use is space qualified. It still remains sticky even in the very challenging environment of space. Traditional methods of grasping like suction cups

00:01:21 don't work because there's no atmosphere. And anything sticky-- and they're called pressure sensitive adhesives-- in the cold, it basically becomes brittle and no longer sticks. We've tested it on free floating platforms both at Stanford and at Jet Propulsion Labs where our collaborators are. With their help, we've tested it on the zero gravity parabolic flight airplane. And then finally, Aaron Parnassus Group at Jet Propulsion Labs made a version of the grippers

00:01:46 that we have that went up to the International Space Station. We also imagine that it could be used for small robots that climb around structures in space in order to do maintenance or inspections. What we design is a proof of concept prototype and then what needs to eventually happen is make a sturdy gripper that will go on the end of a robot arm in space. [MUSIC PLAYING]

00:02:19 For more, please visit us at stanford.edu.