With a goal to revolutionize cellular communications, Penn engineers have developed an adjustable filter that can successfully prevent interference, even in higher-frequency bands of the electromagnetic spectrum.

“I hope it will enable the next generation of wireless communications,” said Troy Olsson, Associate Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering (ESE) at Penn Engineering and the senior author of a new paper in Nature Communications that describes the filter.

The electromagnetic spectrum itself is one of the modern world’s most precious resources; only a tiny fraction of the spectrum, mostly radio waves, representing less than one billionth of one percent of the overall spectrum, is suitable for wireless communication.

The bands of that fraction of the spectrum are carefully controlled by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which only recently made available the Frequency Range 3 (FR3) band, including frequencies from about 7 GHz to 24 GHz, for commercial use.

To date, wireless communications have mostly used lower-frequency bands. “Right now we work from 600 MHz to 6 GHz,” said Olsson. “That’s 5G, 4G, 3G.” Wireless devices use different filters for different frequencies, with the effect that covering all frequencies or bands requires large numbers of filters that take up substantial space.

“The FR3 band is most likely to roll out for 6G or Next G,” said Olsson, referring to the next generation of cellular networks, “and right now the performance of small-filter and low-loss switch technologies in those bands is highly limited. Having a filter that could be tunable across those bands means not having to put in another 100+ filters in your phone with many different switches. A filter like the one we created is the most viable path to using the FR3 band.”

One complication posed by using higher-frequency bands is that many frequencies have already been reserved for satellites. “Elon Musk’s Starlink works in those bands,” said Olsson. “The military — they’ve already been crowded out of many lower bands. They’re not going to give up radar frequencies that sit right in those bands, or their satellite communications.”

As a result, Olsson’s lab designed the filter to be adjustable, so that engineers can use it to selectively filter different frequencies, rather than have to employ separate filters. “Being tunable is going to be really important,” Olsson added, “because at these higher frequencies you may not always have a dedicated block of spectrum just for commercial use.”

What makes the filter adjustable is a unique material, “yttrium iron garnet” (YIG), a blend of yttrium, a rare earth metal, along with iron and oxygen. “What’s special about YIG is that it propagates a magnetic spin wave,” said Olsson, referring to the type of wave created in magnetic materials when electrons spin in a synchronized fashion.

When exposed to a magnetic field, the magnetic spin wave generated by YIG changes frequency. “By adjusting the magnetic field,” said Xingyu Du, a doctoral student in Olsson’s lab and the first author of the paper, “the YIG filter achieves continuous frequency tuning across an extremely broad frequency band.”

As a result, the new filter can be tuned to any frequency between 3.4 GHz and 11.1 GHz, which covers much of the new territory the FCC has opened up in the FR3 band.

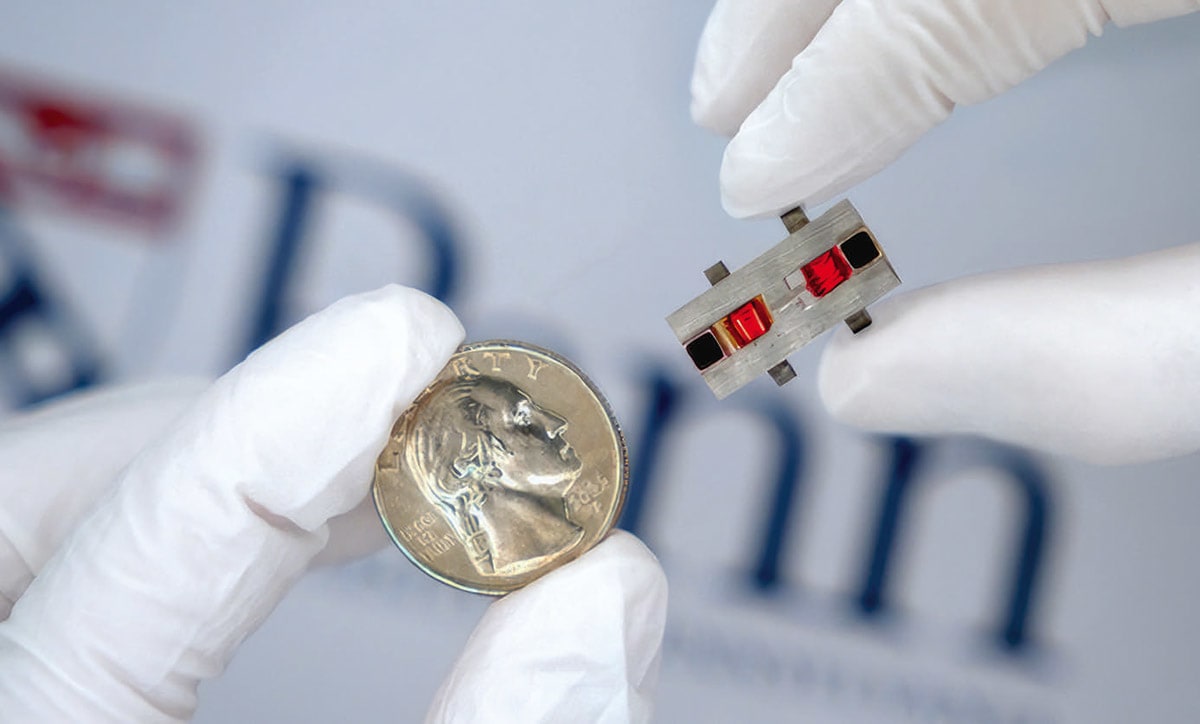

In addition to being tunable, the new filter is also tiny — about the same size as a quarter, in contrast to previous generations of YIG filters, which resembled large packs of index cards.

While YIG was discovered in the 1950s, and YIG filters have existed for decades, the combination of the novel circuit with extremely thin YIG films micromachined in the Singh Center for Nanotechnology dramatically reduced the new filter’s power consumption and size. “Our filter is 10 times smaller than current commercial YIG filters,” said Du.

For more information, contact Holly Wojcik at