Inspired by the movements of a tiny parasitic worm, Georgia Tech engineers have created a five-inch soft robot that can jump as high as a basketball hoop.

Their device, a silicone rod with a carbon-fiber spine, can leap 10 feet high even though it doesn’t have legs. The researchers made it after watching high-speed video of nematodes pinching themselves into odd shapes to fling themselves forward and backward.

The researchers described the soft robot in Science Robotics. They said their findings could help develop robots capable of jumping across various terrains, at different heights, in multiple directions.

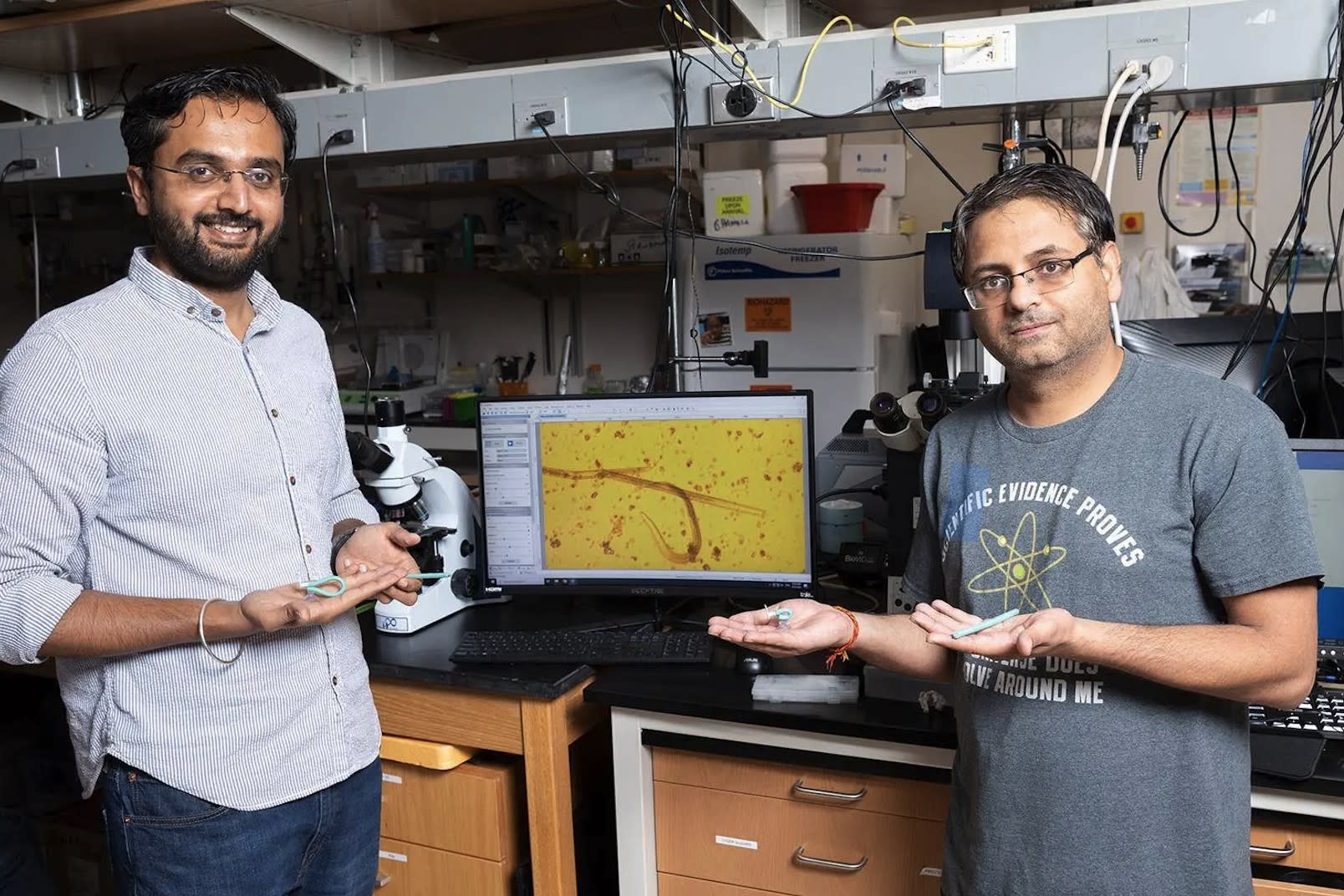

“Nematodes are amazing creatures with bodies thinner than a human hair,” said Lead Co-Author Sunny Kumar, Postdoctoral Researcher in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (ChBE). “They don’t have legs but can jump up to 20 times their body length. That’s like me lying down and somehow leaping onto a three-story building.”

Nematodes, also known as round worms, are among the most abundant creatures on Earth. They live in the environment and within humans, other vertebrates, and plants. They can cause illnesses in their host, which sometimes can be beneficial. For instance, farmers and gardeners use nematodes instead of pesticides to kill invasive insects and protect plants.

One way they latch onto their host before entering their bodies is by jumping. Using high-speed cameras, Lead Author Victor Ortega-Jimenez — former Georgia Tech research scientist who’s now a faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley — watched the creatures bend their bodies into different shapes based on where they wanted to go.

“It took me over a year to develop a reliable method to consistently make these tiny worms leap from a piece of paper and film them for the first time in great detail” Ortega-Jimenez said.

To hop backward, nematodes point their head up while tightening the midpoint of their body to create a kink. The shape is similar to a person in a squat position. From there, the worm uses stored energy in its contorted shape to propel backward, end over end, just like a gymnast doing a backflip.

To jump forward, the worm points its head straight and creates a kink on the opposite end of its body, pointed high in the air. The stance is similar to someone preparing for a standing broad jump. But instead of hopping straight, the worm catapults upward.

“Changing their center of mass allows these creatures to control which way they jump. We’re not aware of any other organism at this tiny scale that can effectively leap in both directions at the same height,” Kumar said.

And they do it despite nearly tying their bodies into a knot.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Kumar.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while getting this robot to jump?

Kumar: Our main purpose was to mimic the jumping kinematics of legless nematodes. In designing the soft robots, the main challenge was enabling them to jump to a height of 10 feet. Generally, a kink represents structural failure, but we aimed to utilize it to store and release energy for jumping. We selected an elastic material (silicone) for the robot's design. The elastic polymer generally has less Young's modulus, raising doubts about whether it can generate sufficient force for such a high jump. This led us to explore methods for enhancing the stiffness of elastic materials. Another significant challenge was achieving this functionality at a small scale, where energy storage and actuation become even more constrained.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how it jumps please?

Kumar: The elastic rod bends into a closed loop so that its ends touch each other, storing energy in the process. When the ends are released, that stored energy is rapidly converted into motion, causing the robot to jump into the air. In this study, the elastic rod bends manually, but this process could be automated in the future.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research/work/etc.? If not, what are your next steps? Where do you go from here?

Kumar: Our next steps involve identifying practical applications for this jumping mechanism and advancing the design through automation and miniaturization. For example, there was recent news that a jumping robot was deployed to the moon, and similar systems are being developed for search and rescue operations, where agility and the ability to navigate rough terrain are essential. We want to create versatile, deployable robots for extreme environments by automating the actuation process and scaling down the system.

Tech Briefs: I know the article is barely two weeks old, but do you have any updates you can share?

Kumar:We are just getting the response from the media and public feedback. People are sharing our research and are surprised by how reversible kink instability is happening in the organism and how we have successfully mimicked that mechanism in our soft robotic system.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Kumar: We also demonstrate an important discovery about directional jumping by changing its centre of mass. We mimicked this unique ability in our soft jumping robot by integrating a 3D-printed component.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any advice for researchers aiming to bring their ideas to fruition (broadly speaking)?

Kumar:I want to give advice to researchers. In nature, every animal reveals unique principles and mechanisms during locomotion or other activities. We can uncover innovative strategies that translate into impactful engineering applications by closely observing such biological systems and understanding the underlying physics.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.