Johns Hopkins University researchers have grown a novel whole-brain organoid, complete with neural tissues and rudimentary blood vessels — an advance that could usher in a new era of research into neuropsychiatric disorders such as autism.

"We've made the next generation of brain organoids," said Lead Author Annie Kathuria, Assistant Professor in JHU's Department of Biomedical Engineering who studies brain development and neuropsychiatric disorders. "Most brain organoids that you see in papers are one brain region, like the cortex or the hindbrain or midbrain. We've grown a rudimentary whole-brain organoid; we call it the multi-region brain organoid (MRBO)."

The research, published in Advanced Science, marks one of the first times scientists have been able to generate an organoid with tissues from each region of the brain connected and acting in concert. Having a human cell-based model of the brain will open possibilities for studying schizophrenia, autism, and other neurological diseases that affect the whole brain — work that typically is conducted in animal models.

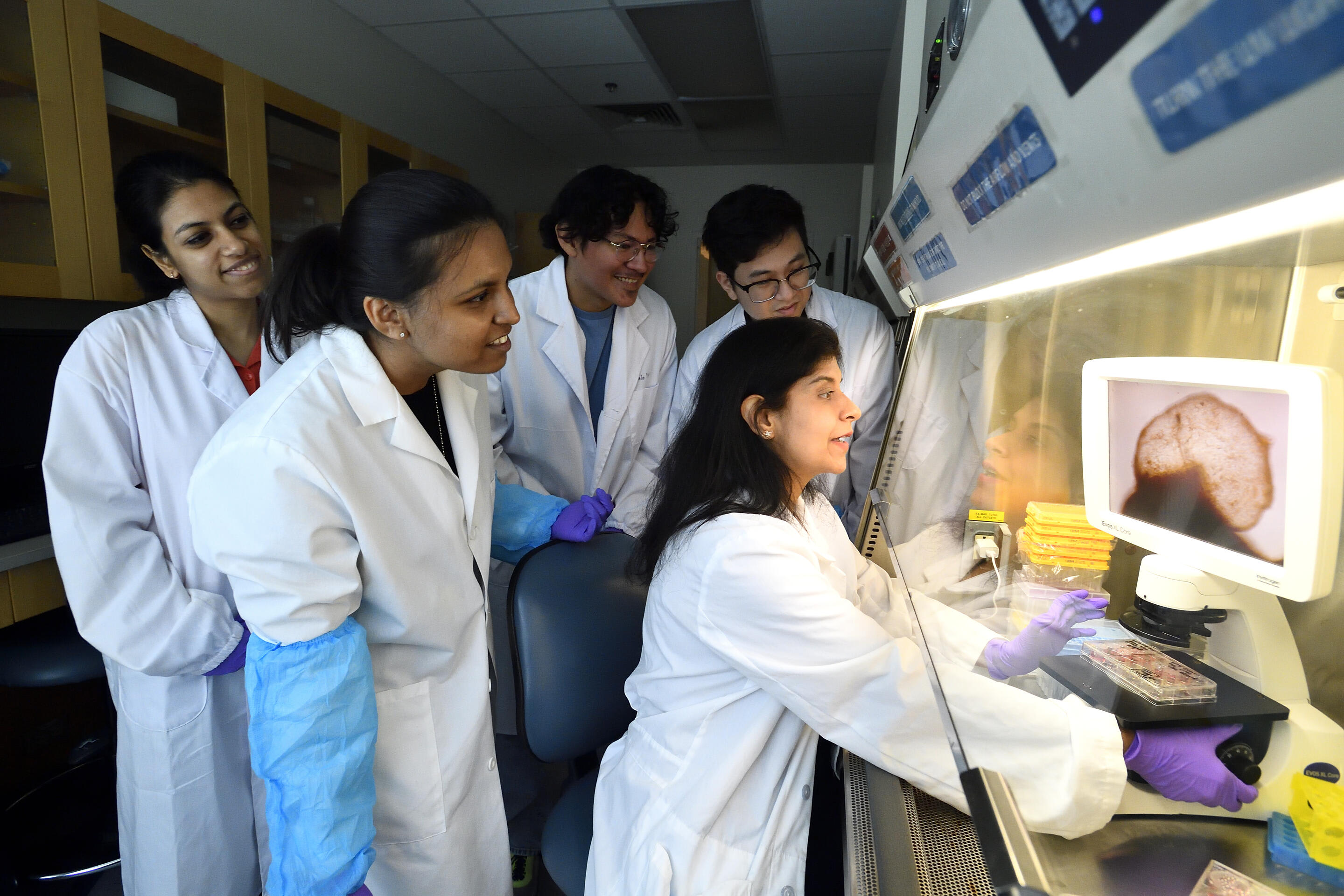

To generate a whole-brain organoid, Kathuria and members of her team first grew neural cells from the separate regions of the brain and rudimentary forms of blood vessels in separate lab dishes. The researchers then stuck the individual parts together with sticky proteins that act as a biological superglue and allowed the tissues to form connections. As the tissues began to grow together, they started producing electrical activity and responding as a network.

The multi-region mini brain organoid retained a broad range of types of neuronal cells, with characteristics resembling a brain in a 40-day-old human fetus. Some 80 percent of the range of types of cells normally seen at the early stages of human brain development was equally expressed in the laboratory-crafted miniaturized brains. Much smaller compared to a real brain — weighing in at 6 million to 7 million neurons compared with tens of billions in adult brains — these organoids provide a unique platform on which to study whole-brain development.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Kathuria.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while growing this MRBO?

Kathuria: The vascularization, because most people grow just the endothelial cells and not the whole blood vessel. That was the most challenging because we wanted not just endothelial cells in there, we wanted the platelet-derived growth factors, the smooth muscle cells. We wanted to make blood vessels inside the brain organoid. We had to play around with a lot of different growth factors, medias to make it work.

Tech Briefs: The article I read says, “The researchers then stuck the individual parts together with sticky proteins that act as a biological super glue and allowed the tissues to form connections. As the tissues began to grow, they started producing electrical activity and responding as a network.” My question is: How long was the process from when you stuck the individual parts together with the sticky proteins to when the MRBO started producing electrical activity and responding as a network?

Kathuria: That was pretty fast. We put them all together 20 days after differentiation, and about 15 days later we saw a little activity. But it kept growing and growing and growing and getting stronger and stronger. And at around 65 days, they were producing a lot of spontaneous activity on their own. We didn't have to do anything or stimulate them with an external chemical or electrical stimulant. They just started doing it on their own 15 days later. And to be honest, when I have seen them under a microscope, they start forming connections in about two days. But the electrical activity appears at around 15 days. And then we followed it every 10 days, 35, 45, 55, 65, we even did 85 days, and now we have them around four months old these days, and they're like synchronized pattern oscillation activities now.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research, work, etc.?

Kathuria: I have two plans. The first one is that my lab is very interested in studying neuropsychiatric disorders, and my Ph.D. was on autism. These disorders have a lot of similarities, especially autism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, a lot of synaptic deficits, a lot of connection deficits within the brain. We've already made all these organoids with separate, but also with patient-derived lines.

We are looking at the MRBO as a whole with autism and with schizophrenia. Think of this as a preclinical clinical trial. Which pathways go wrong? Now we can put drugs, small molecule drugs, to test them, and we're using already-FDA-approved drugs and rerouting them to see if they work. There are some we're using from previous animal studies, but we're trying to basically do a clinical trial in a dish.

The second part is my tissue engineering bit. Right now, they're not hemodynamic; they don't have flow in them. But we are getting these rudimentary blood vessels, and we want the blood vessels to start channeling media in them. Think of it this way: This is iPhone version one; we are going to go to iPhone version 15 someday.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you'd like to add that I didn't touch upon?

Kathuria: There is an advantage to having these whole-brain organoids, instead of just one region. Whenever a neurological disease occurs — Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, schizophrenia, autism, even cancer — it doesn't affect one part of the brain; it affects all parts of the brain. So this kind of model, even though I am biased, helps us understand how one area affects the other. And these connections are important to early drug discovery. Right now, the attrition rate for neurological disorders is over 90 percent. So, this could be useful as a tool to reduce that attrition rate.