Tech Briefs: What is the mechanism of stir welding?

Piyush Upadhyay: A spinning tool rotating at a high rate of speed plunges into two pieces of metal. As the tool begins to move, it pulls the metals into itself and softens and mixes them, creating a powerful weld — one that can securely join similar and dissimilar materials (particularly metals and alloys) without rivets, fasteners, or adhesives.

Tech Briefs: Does stir welding melt the material being welded?

Upadhyay: Friction stir welding doesn’t melt the material: The rotating tool generates frictional heat that raises the temperature enough to soften it. This softening allows the material to plasticize in order to make it workable. The tool can join two (or more) pieces together into a solid-state weld. The ability to join materials in the solid state has multiple benefits, including the refinement of the microstructure, which leads to significantly improved properties of the weld. With friction stir welding, manufacturers can create both point joints and long, continuous welds.

Tech Briefs: How does friction stir welding differ from standard spot welding?

Upadhyay: Friction stir welding is vastly different from conventional spot welding. Resistance spot welding melts metal with electricity. Friction stir welding does not melt the metal — it joins materials in a solid phase. With conventional spot welding, mechanical fasteners, such as rivets and screws, often have to be used to add extra strength. Friction stir welding produces joints that are typically stronger, lighter, and more durable than those made with conventional spot welds, mechanical fasteners, or adhesives — while also avoiding added weight, material costs, or long-term degradation of joints.

Tech Briefs: How does its energy use compare with conventional techniques?

Upadhyay: The process of melting materials, as is the case with conventional fusion welding, is an inefficient process that puts significant excess energy into the materials to be welded. As a result, the process requires much more energy than absolutely needed, most of which is dissipated to the environment as waste heat. Since friction stir welding does not melt the material, and the frictional heat is concentrated only where the joint is to be made, the process is inherently more efficient, with much less wasted energy. This is known as process intensification and has a drastic effect on the energy requirements, as well as the cycle times to produce a weld.

Tech Briefs: Can friction stir welding be used with a variety of different metals?

Upadhyay: Vehicle structures are ideally designed for light weight, but available welding technologies influence which materials can actually be used. Traditional spot welding struggles with lightweight alloys like aluminum, which can melt and weaken under high heat. Since friction stir welding avoids melting, it can reliably join lighter, thinner materials, as well as thicker, more brittle materials that might crack if riveted. It can even join materials that are not possible to fusion weld. This provides manufacturers and vehicle designers with more freedom to engineer lighter vehicles without compromising strength.

Tech Briefs: How does the strength of these welds compare with conventional types?

Upadhyay: Because friction stir welding is a solid-state process (the metal softens but never melts), it avoids many of the defects that come from melting and re-solidifying metal, such as cracks, pores, and weak spots. Instead, the stirring action blends the materials together, creating an exceptionally uniform joint. The result is often stronger and more fatigue-resistant than a traditional spot weld, which can have brittle zones or inconsistencies.

Tech Briefs: Will you need to design a special heavy-duty robot to hold the stir welding tool?

Upadhyay: No. The breakthrough with our self-reacting fixture is that we no longer need a massive, custom-built robot to apply friction stir welding on a typical assembly line. Traditional friction stir welding puts all of its force into the assembly line supports, which has meant only very heavy, expensive robots could handle it. With our self-fixturing system, the force is captured by the tool itself and isolated to just the tooling. That means (once fully developed) the robot’s job will simply be to guide the tool into place, rather than react to thousands of pounds of force.

Tech Briefs: Is it difficult for the tool to stand up against so much force?

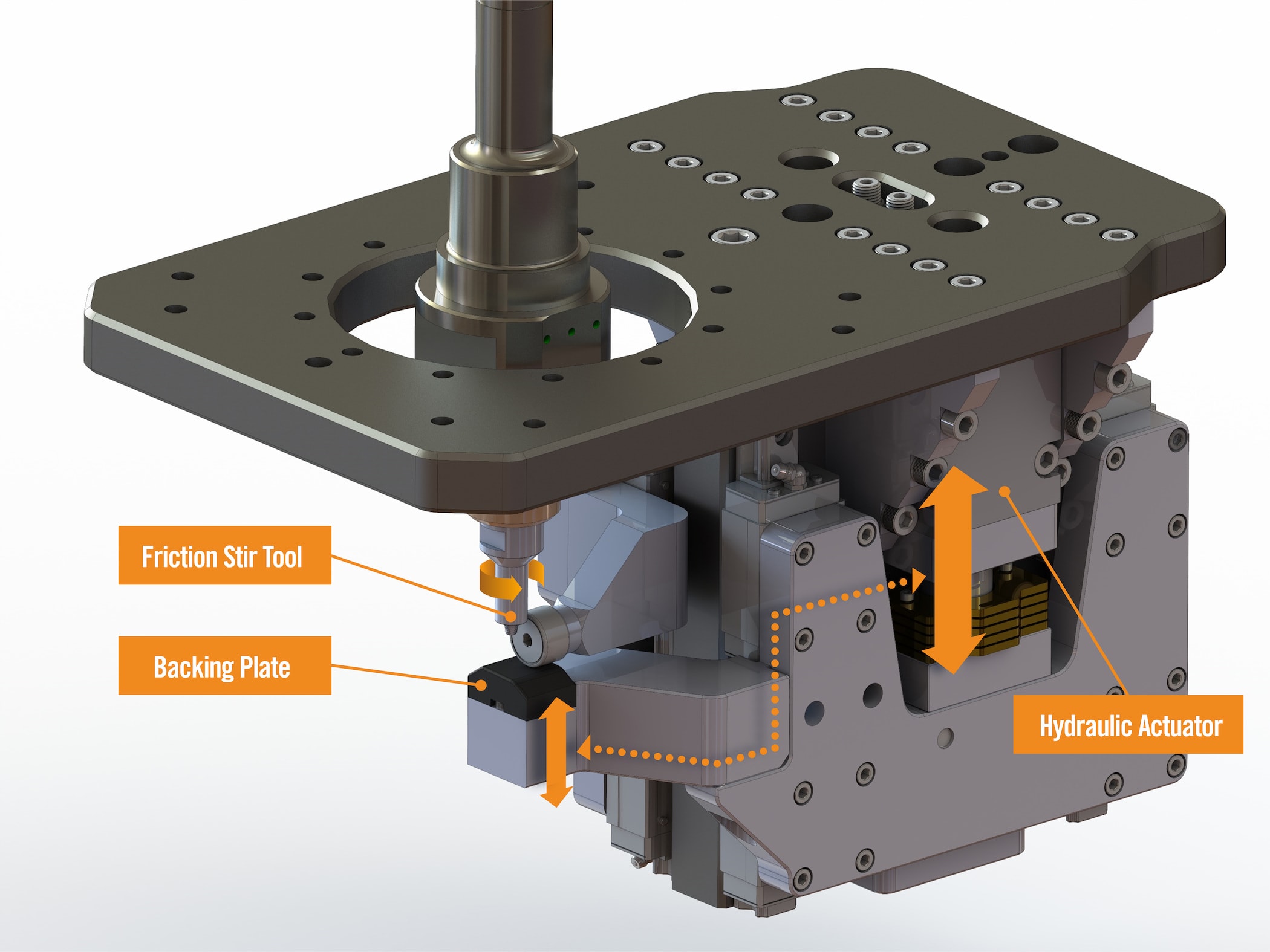

Upadhyay: That’s exactly the engineering challenge we’ve been solving. By pairing the friction stir tool with a sliding, built-in backing plate and a hydraulic system, we’ve created the first version of a closed loop that contains those forces. Instead of pushing against the assembly line, the tool essentially pushes against itself. This makes it possible to handle the forces of friction stir welding without needing an external anvil or a super-heavy robot.

Tech Briefs: Would the tool have to be made of harder metals than what it’s welding and does that limit the types of metals that can be welded?

Upadhyay: Yes, the tool must be tougher than the materials being joined. That is true for any manufacturing cutting or forming tool. But this does not limit us to just one or two metals. Custom tool designs and alloys that can handle high-temperature materials with acceptable wear rates allow us to weld a wide range of materials in both similar and dissimilar alloy combinations.

Tech Briefs: If you’re welding dissimilar materials, would they have to be chosen for compatibility with each other and with the stir tool?

Upadhyay: Yes, material compatibility matters, just like with any joining process, especially when you need to consider corrosion resistance performance between them. The metals need to have similar enough properties so that they can be plasticized and mixed without creating weak or brittle zones. That said, one of the strengths of friction stir welding is that it can join combinations that are very difficult to join using conventional methods — like aluminum to magnesium or aluminum to steel. And since the tool is designed to be harder than both materials, that isn’t usually the limiting factor.

Tech Briefs: You mentioned a hydraulic system — how is that used?

Upadhyay: When the friction stir tool presses into metal, it can create thousands of pounds of force. In the old system, that force had to be absorbed by an anvil on the backside of the weld and by the robot itself. With our new concept, the tool and backing plate are connected to a hydraulic system that contains the force isolated to the frame attachment. In other words, the tool pushes against its own backing plate — not against the assembly line. We call that a closed loop because the forces balance within the tool instead of being transmitted outside.

Tech Briefs: What does it mean that your process pulls the material into the tool?

Upadhyay: In friction stir welding, the rotating tool does not just press down — the material also needs to flow smoothly around and behind the tool so the joint forms evenly and without distortion. Our new self-fixturing design adds a mechanism that helps pull the material into the tool, rather than relying on the robot to push it forward. This drawing action improves weld quality and also reduces the amount of force the robot must apply.

Tech Briefs: Have you looked into particular applications?

Upadhyay: Yes. One of the most immediate automotive applications is joining thick, high-strength aluminum stampings in both long, continuous welds, and also short stitches for parts like roof rails, door surrounds, frames, and structural panels. Because these parts have complex, three-dimensional contours, they can only be joined with a robot — and our self-fixturing system eliminates the need for bulky backing anvils and clamping systems. That makes these parts ideal applications for the technology and hence, enables the introduction of friction stir welding on the assembly line itself vs. doing the welding offline and then bringing the part to the assembly line. It is a much more efficient and affordable process.

Beyond vehicles, the self-fixturing concept could also benefit aerospace, rail, shipbuilding, and other industries with large, complex parts that are difficult to support with traditional anvils and clamping systems. By capturing the welding forces within the tool itself, our system makes friction stir welding practical in places where rigid fixturing has always been the barrier.

Tech Briefs: Do you have a sense of when this might be applied in industry?

Upadhyay: We’ve been fortunate to have support from DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office to develop this concept and advance the technologies required. Our first prototype has already shown strong promise, and we are now teaming with robotics and fixture suppliers within the U.S. to transfer the innovations to second- and third-generation working prototypes. Those will let us showcase the technology and collect data not just on its technical performance, but also on its economic viability on the factory floor. It hasn’t been applied to a real assembly line yet, but we’re optimistic that we’ll be able to demonstrate self-fixturing friction stir in a real-world industrial setting in the near future.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything you’d like to add?

Upadhyay: Beyond improving the welding method, this innovation gives manufacturers new freedom to design lighter, stronger, and more efficient products. One of the biggest hurdles in adopting any new process is qualification — if you cannot assure part quality, you do not have a manufacturing process. The good news is that with friction stir welding, we capture detailed data on forces and temperatures during welding, and we can correlate that data directly to joint quality. That gives us a built-in path to non-destructive evaluation. At the same time, we are addressing other real-world challenges: tool life for harder materials, where we are collecting data on wear rates and tool change-out schedules; tool design innovations that minimize wear; and modeling, which helps us determine the best placement of joints in complex parts.