Researchers at the University of Sydney and start-up Dewpoint Innovations have developed a nanoengineered polymer paint-like coating that can passively cool buildings and capture water directly from the air — all without energy input.

The invention could help tackle global water scarcity and help cool buildings, reducing the need for energy-intensive systems.

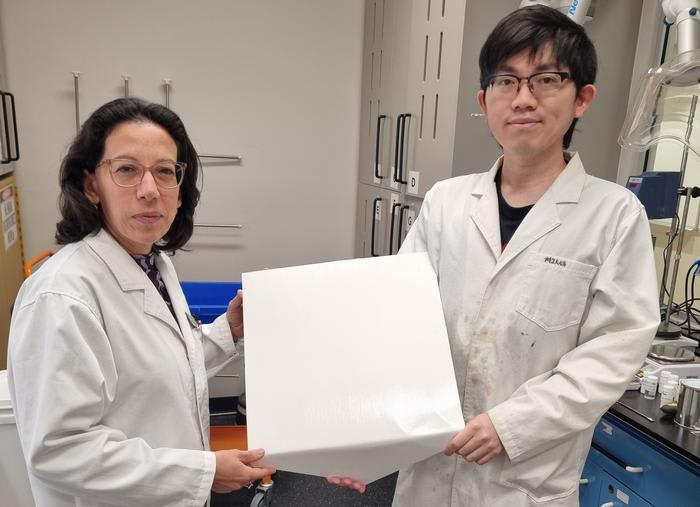

The research team led by Professor Chiara Neto created a porous polymer coating that reflects up to 97 percent of sunlight and radiates heat into the air, keeping surfaces up to six degrees cooler than the surrounding air even under direct sun. This process creates ideal conditions for atmospheric water vapor to condense into droplets on the cooler surface, the way steam condenses on your bathroom mirror.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Neto.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing this polymer paint-like coating?

Neto: There were several challenges. With respect to the coatings described in the published paper, producing controlled nano- and microporosity on a relatively large scale (e.g. 20 x 20 cm2) was challenging, as well as designing the topcoat that helped the condensed water droplets to easily roll off the surface. There were also challenges in translating these lab-scale surfaces into the commercial water-based paint that is being commercialized by start-up Dewpoint Innovations. Here the main challenge is that few people know about the existence of cool roof paint, and fewer have ever considered that as a potential source of clean water.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how it works please?

Neto: We designed paint-like coatings with high reflectivity of the sun rays (92 percent) and high emissivity of heat (95 percent), so that they cool spontaneously when exposed to the sky, up to 6 °C below air temperature. When the weather conditions are right, the coatings become so cool that they start to condense vapor from the air into droplets of water (dew). Dew was collected even during the day because the coatings cool by passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC, also called sky cooling). PDRC materials can cool below ambient temperature because they do not heat up in the sun, due to strong reflection of sunlight (in the wavelength range 0.3–2.5 μm), and emit thermal radiation to the cold of space within the atmospheric window of the IR spectrum, i.e. in the mid-infrared wavelengths in the range 8–13 μm. The atmosphere is almost transparent to IR radiation in that region, which means that heat from the surface can be directly dumped towards the cold of deep space (temperature close to -270 °C), allowing the surface to cool. PDRC extends the period over which dew can be collected into daytime hours, when other surfaces heat up under the sun, and therefore increases the collected volume of water. The maximum rate of water we collected is around 400 ml/m2/day, produced by a typical cooling of the surface of 2-3 °C below air temperature. This PDRC effect delivers much cooler roofs for buildings compared to black roofs (typically over 25 °C cooler than a black roof during the daytime) and superior even to conventional light-colored materials (typical reflectance of only ≈70 percent), leading to much lower heat loading for buildings and a strong reduction in the heat island effect.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research/work/etc.? If not, what are your next steps?

Neto: We continue to work on improving the water-based paint to increase the efficiency of water capture, and we are designing pilot studies to demonstrate the capability of the water capture and durability in different climatic conditions.

Tech Briefs: I know the article is not even a week old, but do you have any updates you can share?

Neto: The publication of the article has produced great interest in this passive cooling solution, which is badly needed, because the public’s awareness of cool-roof paint has been low so far. We hope that increased attention will result in a public push to change building practices and codes toward more sustainable and energy-efficient buildings that incorporate cool-roof paints. We need to see a similar campaign of incentives by the government to that used for solar panels, leading to widespread adoption and understanding of the benefits.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Neto: Cool-roof paints have been shown to be able to reduce energy consumption due to cooling in buildings by as much as 40 percent. If applied on the scale of entire suburbs, they could decrease air temperature in those suburbs in summer by up to 2 °C. It is a technology that is badly needed in Australia and many areas of the world where mortality and morbidity due to heat are in drastic increase. For individuals living without air conditioning, reducing the indoor temperature passively could bring significant benefits even with a 2 °C reduction, especially in conjunction with the use of fans.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any advice for researchers aiming to bring their ideas to fruition?

Neto: Commercializing research is a rewarding but highly demanding job. It requires not a single individual but a team of motivated and positive people, and an ecosystem that helps researchers at each step of the way. Consulting with colleagues and experts in commercialization is important.