A system for determining the locations of nearby lightning strikes from electric-field and acoustic measurements has been developed. This system evolved from the system described in "System Locates Lightning Strikes to Within Meters" (KSC-11992), NASA Tech Briefs, Vol. 24, No. 7 (July 2000), page 38. The basic concept of both the present and the previous system is an extension of the concept of estimating the distance of a lightning strike from the difference between the times of arrival of the visible flash and the audible thunder. Like the previous system, the present system locates lightning strikes to within errors of the order of a meter. However, the present system is more compact and more readily deployable, as explained below.

The previous system included a network of at least three receiving stations at locations up to about 0.8 km apart from each other and from the general area wherein lightning strikes of interest could occur. Each receiving station was equipped with an antenna for measuring the electric field generated by a lightning strike and a microphone for measuring the associated acoustic field (thunder). For each strike, the system measured the difference between the times of arrival of the electric-field and thunder pulses at each station, computed the distance of the strike from the time difference and the speed of sound (about 320 m/s), then used the distances from all three (or more) receiving stations to determine the location of the strike.

The main disadvantage of the previous system was the need to set up multiple receiving stations and to lay power and data cables to connect the receiving stations to a central data-collecting station. In contrast, the present system includes only one receiving station and can thus be set up more quickly and easily.

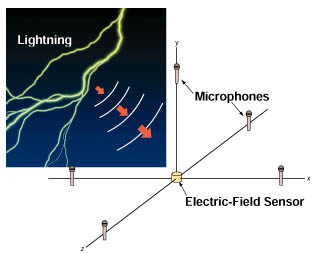

The single receiving station in the present system (see figure) includes an electric-field sensor at the center of a horizontal circle of 1- or 2-m radius, four microphones placed on the circle at 90° intervals, and a fifth microphone 1 or 2 m above the center. A nearby lightning strike causes the electric-field sensor to put out a pulse that is used to start a timer and to trigger the digitization and recording of microphone outputs as functions of time.

The differences between times of arrival of thunder at the five microphones range up to a few milliseconds. These differences are determined, within <10 µs, from real-time digital cross-correlations among the microphone outputs. The direction from which the thunder came (and thus the direction to the lightning strike) is computed by finding the set of direction cosines of the sound-propagation vector that yields the least-squares best fit to the time-of-arrival differences, given the known microphone position vectors and the known speed of sound. For the purpose of computing the direction, it is assumed that the distance to the lightning strike is much greater than the microphone baseline. This distance is readily computed from the time between the measured electric-field pulse and the time of arrival of thunder at one of the microphones.

The main challenge observed during field tests of the system lay in determining the starting times of thunder signals. A thunderclap of interest from a nearby lightning strike can be accompanied by (1) thunder from an earlier and more distant lightning strike, and/or (2) popping sounds generated by streamers that occur alongside the main lightning current path and carry a small fraction of the total current. Because higher-frequency sounds are attenuated over distance more than lower-frequency sounds are, one can discriminate against thunder of distant origin by high-pass filtering (the filter cutoff frequency used in practice is 100 Hz).

Both the thunderclap of interest and the popping sounds consist primarily of frequencies up to several kilohertz, but a typical thunderclap lasts >100 ms, while the popping sounds are of much shorter duration. Thus, one can distinguish between the sound from the main current path and the sounds from the streamers by discarding short, high-frequency signals. The starting time of the thunder signal is thus identified as the starting time of a high-frequency signal that lasts at least 100 ms. The portion of the history of each microphone output chosen for use in computing the cross-correlations is the portion starting 50 ms before and ending 50 ms after the starting time identified in this manner.

This work was done by Curtis M. Ihlefeld of Kennedy Space Center and Pedro J. Medelius, Howard James Simpson, and Stan Starr of Dynacs Engineering Co., Inc.

In accordance with Public Law 96-517, the contractor has elected to retain title to this invention. Inquiries concerning rights for its commercial use should be addressed to

Michael Guzman

New Technology Administrator

Dynacs Engineering Co., Inc.

P.O. Box 21087

Kennedy Space Center, FL 32815

(321) 867-3322

Fax: (321) 867-7534

E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Refer to KSC-12035