NASA Technology

When NASA wanted to build the greenest, most energy-efficient Federal building in the United States, it needed a way to keep track of the energy being consumed. After all, good design is only the first step—at a certain point, people were going to be using the space.

Architects designed the newest building at Ames Research Center, dubbed Sustainability Base, to reduce as much as possible the energy its occupants need. For instance, it includes massive windows and skylights, with all structural load carried by external supports rather than by light-blocking pillars. That way, occupants in the 50,000-square-foot space have less need for artificial light during daylight hours.

In April 2012, thanks to its environmentally conscious design, Sustainability Base received a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED, Platinum certification by the U.S. Green Building Council—the highest-level certification it offers. It was the first newly constructed Federal building to receive the rating.

But NASA didn’t want to stop there, explains Sustainability Base research lead Rodney Martin. It wanted to ensure that, even after construction was complete, the occupants were making the best use of energy on a day-to-day basis—and to do that, Sustainability Base needed a mechanism to monitor energy consumption. It’s fairly easy to know how much energy an entire building is using, explains Martin, “but that doesn’t give individual occupants much info on what they can do to reduce that number.

“We need ground truth. What’s consuming the most energy?” Martin says.

Technology Transfer

Enter Verdigris Technologies Inc.: the Moffett Field, California-based company designed a sensor that “listens” to electronic signals as they pass through a circuit panel and analyzes their fluctuations using a deep packet inspection algorithm—the same technology the National Security Agency uses to monitor text messages between suspected terrorists.

The algorithm allows the sensor to differentiate between the devices using electricity in the building. So if you plug in an iPhone charger, it’ll know. And if your refrigerator has been chugging along using a certain amount of power every week and suddenly that number starts growing, it’ll know that too.

Similarly if, like company cofounder Mark Chung, you go on vacation but your pool pump motor gets stuck in the “on” position, you’ll find out about it before you come home to a massive electricity bill. Chung, frustrated by the inexplicable electricity spike and the cumbersome and inaccurate tools available to help him identify the problem, was determined to create a better solution.

The electrical engineer and his colleague, Jonathan Chu, also an engineer, had been working with deep packet inspection algorithms to help telecommunication companies differentiate between types of data being transmitted. Some, like text messages, need to be extremely accurate but could stand a short delay. Others, like voice calls, need to be sent in real time, even if they end up slightly garbled. “Using deep packet inspection algorithms, the network is able to detect the different type of packets and develop priority routing schemes,” Chung explained.

Chung and Chu used the same method when they designed their electricity sensor. “We thought we’d run deep packet inspection and see if we can pick up the big thing,” Chung recalls. “And the surprise was, ‘Oh, I can pick up a lot of things.’”

When Verdigris approached NASA about a potential research partnership, they were put in touch with the team at Sustainability Base, who decided to incorporate a pilot system based on Verdigris’ early prototypes. The company entered into a nonreimbursable Space Act Agreement with NASA, a decision, Chung says, that launched the start-up into the big time.

“We started to work with them to find a path to develop our sensor technology and for NASA to work on validating whether what we were predicting with our algorithm was true,” he explains. “We’d been doing that in our lab with 15 or 20 devices, and suddenly we were in a wing of the building with hundreds of thousands of devices, in a real-world setting.”

That was a crucial step in developing the device for the market, Chung says. “With our system, the first time you plug it in, it can differentiate between devices, but you have to teach it what they are. That was one of the big advantages of working with NASA: Sustainability Base was like a virtual playground for us to teach the system.

“It absolutely got us going faster than we would have otherwise,” Chung emphasizes, noting that, “working with NASA also extended some credibility to us. It opened the doors for conversations with other customers.”

Benefits

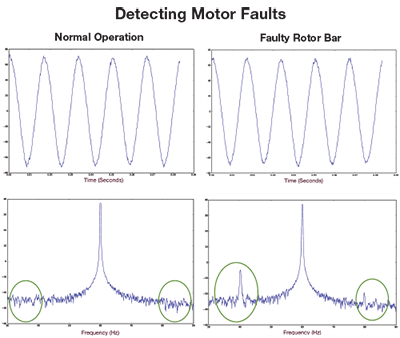

The Verdigris system continuously monitors electricity consumption and sends alerts when there are problems, whether lights are turning on automatically when no one is around or a machine is no longer working the way it should and could be heading toward a breakdown.

The latter is something that could prove extremely useful for NASA beyond Sustainability Base, says Rosalind Grymes, deputy director of the partnership directorate at Ames Research Center.

Not only could a Verdigris sensor help mission scientists design equipment that optimizes energy use, she says, but it could also predict when a failure is about to happen. In the case of a robot on Mars, where repairing the instrument is often impossible, that kind of information could be game-changing.

“When you have advance notice, you may be able to isolate a device, so it doesn’t bring down other devices. You may be able to make remote changes that prevent the failure,” she says.

And if you can’t do anything? Well, at least you’d still have time. “You can now optimize the use of that device from now until the predicted failure, so you can get the best science out of the remainder of its life,” she says.

That function has proven to be a big selling point for Verdigris’ commercial customers, which include major hotels, corporate offices, hospitals, and manufacturers. Once installed in a building, the information gathered by the sensor is sent to the managers in weekly emailed reports and can be monitored by smartphone or on the Web.

The information is also compared to data gathered by Verdigris sensors at other sites and stored in the cloud, increasing the data points included in the baseline. “One example, at a San Francisco hotel, was thatwe found dishwasher equipment not going through its heat cycle properly,” recalls Chung. The system was able to identify the problem because the dishwasher wasn’t using as much power as expected to reach the heat needed to properly sanitize the dishes.

“They wouldn’t have caught this through their normal inspection process,” he says, which means that, without the Verdigris system, the hotel may not have realized there was a problem until guests got sick.

“That was a good demonstration of the kind of device that NASA is also so critically interested in,” Grymes added. “We don’t want to wait for a device to fail, because the consequence is a really bad day in space.”