Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan have created the world’s smallest fully programmable, autonomous robots: microscopic swimming machines that can independently sense and respond to their surroundings, operate for months, and cost just a penny each.

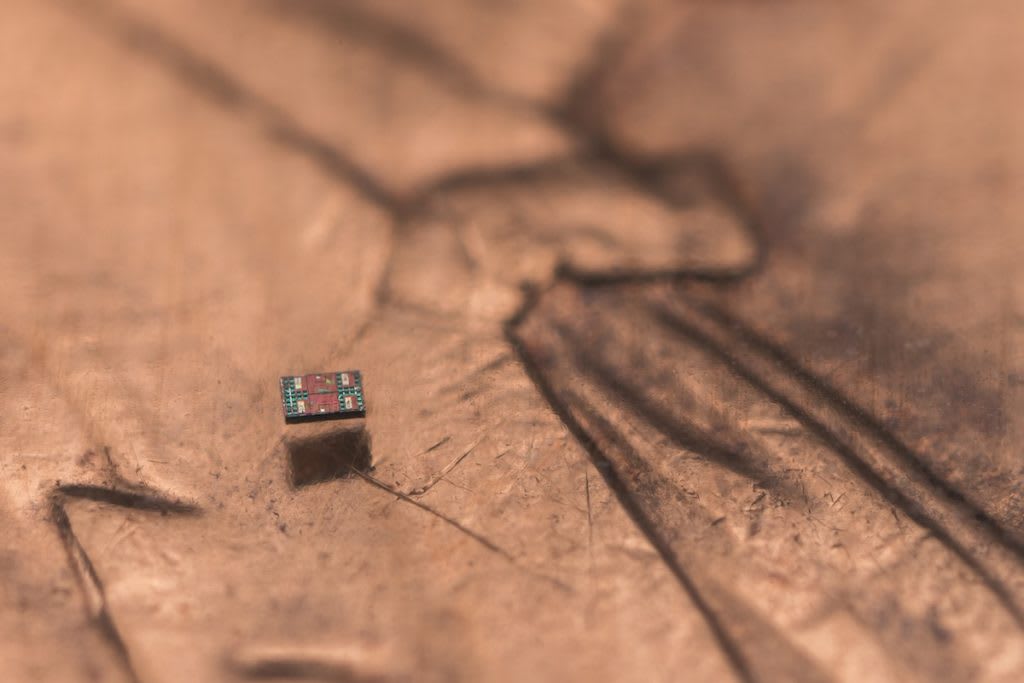

Barely visible to the naked eye, each robot measures about 200 by 300 by 50 micrometers — smaller than a grain of salt. Operating at the scale of many biological microorganisms, the robots could advance medicine by monitoring the health of individual cells and manufacturing by helping construct microscale devices.

Powered by light, the robots carry microscopic computers and can be programmed to move in complex patterns, sense local temperatures and adjust their paths accordingly.

Described in Science Robotics and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the robots operate without tethers, magnetic fields, or joystick-like control from the outside, making them the first truly autonomous, programmable robots at this scale.

“We’ve made autonomous robots 10,000 times smaller,” said Senior Author Marc Miskin, Assistant Professor, Electrical and Systems Engineering, Penn Engineering. “That opens up an entirely new scale for programmable robots.”

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Miskin.

Tech Briefs: The article I read says that it took five years of collaboration with Michigan to get the first working robot. What was the biggest technical challenge you faced over that time and how do you overcome it?

Miskin: Well, in fairness, five years ago was COVID. [Laughs]

Tech Briefs: Fair point. [Laughs]

Miskin: We started this collaboration in 2020; I met David [Blaauw, Team Lead at the University of Michigan] in either 2019 or early 2020. We came back from a conference and realized that we should work together. David's building tiny robots; I'm building tiny robots. David's building tiny computers, etc. Maybe two months after that, everything was shut down. So, I don't know if it really had to take us five years. I think it was that two of those years we were just cobbling things together.

But, to answer your question, the biggest challenge in a lot of these things is just making the pieces fit together. Classically in nano, it's usually the case of ‘You can do A, you can do B, but you have no idea how to do A and B together,’ because the parts don't work or the materials are incompatible or the ways that you made them don't fit.

And for a robot, which has many different systems that all need to play as part of the same system, that becomes a really big challenge. You need to figure out if I've got this little, tiny space and I've got a little, tiny bit of power, how do I distribute it between all these systems so I don't use it all up? How much should go to computing? How much should go to actuation? And how do you build all of those parts where, as you build one, you don't break the things you previously constructed. A lot of the engineering work goes into addressing that.

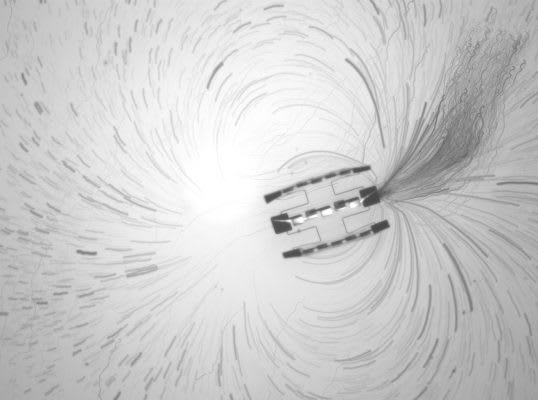

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how such a small robot can swim?

Miskin: This particular robot uses a technique of propulsion that we call electrokinetic propulsion. The idea is it's basically a sort of self-electrophoresis. The robot lives in water, and it has electrodes on its surface — they're just pretty much metal pads. You pass a current through the water from the plus to the minus terminal. When you do that, charges move through the fluid, but as they move they bump into the water molecules and that creates a fluid flow. So, if you engineer that correctly, you can use that flow to act as a source of propulsion.

The analogy we like to use is the flow you create is almost like being in a river. That's what's moving the robot along, but you are the thing that's making the river move, right? The electrical current is what created the fluid motion in the first place.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research, work, etc.? And if not, where are your next steps?

Miskin: There are next steps. The big thing we're really interested in right now is communication between the robots. If you're small, there will always be limits to how smart you can be or how much work you can do or how much energy you can have. You're just constrained by the physical dimensions of the device. The workaround is you collaborate; it's what nature does, right? Cells by themselves aren't super interesting; collections of cells or organisms, though, they're very interesting. So if you want to collaborate, if you want to work together, the first thing you need to figure out is how to communicate.

You have to be able to build robots that can exchange information between one another, and do that in a way that's sophisticated enough to where they can actually change each other's behaviors. So, the next major technological goal we're going after is how do we get robots that can talk to each other over some local range. Then that invites a whole bunch of robotics questions as well, like how do you program them? OK, they can talk, but what are the rules they should use to generate interesting behaviors that you could only achieve as a group that you couldn't achieve as an individual? Those are two really deep, fun questions.

The first part's pretty much on the engineering side of what's a good communication strategy for a small robot. And then the second is a little further up the chain and more on the robotics and science side of how do you actually get them to organize and do something useful.