Spinoff is NASA's annual publication featuring successfully commercialized NASA technology. This commercialization has contributed to the development of products and services in the fields of health and medicine, consumer goods, transportation, public safety, computer technology, and environmental resources.

When Michael Markesbery, future co-founder of Oros (Cincinnati, OH), climbed the tallest mountain in the Swiss Alps, he wore so many bulky layers that he could barely move his arms. He didn't know it, but something already existed that could make incredibly warm outerwear with far less bulk, and it owes much of its development to NASA.

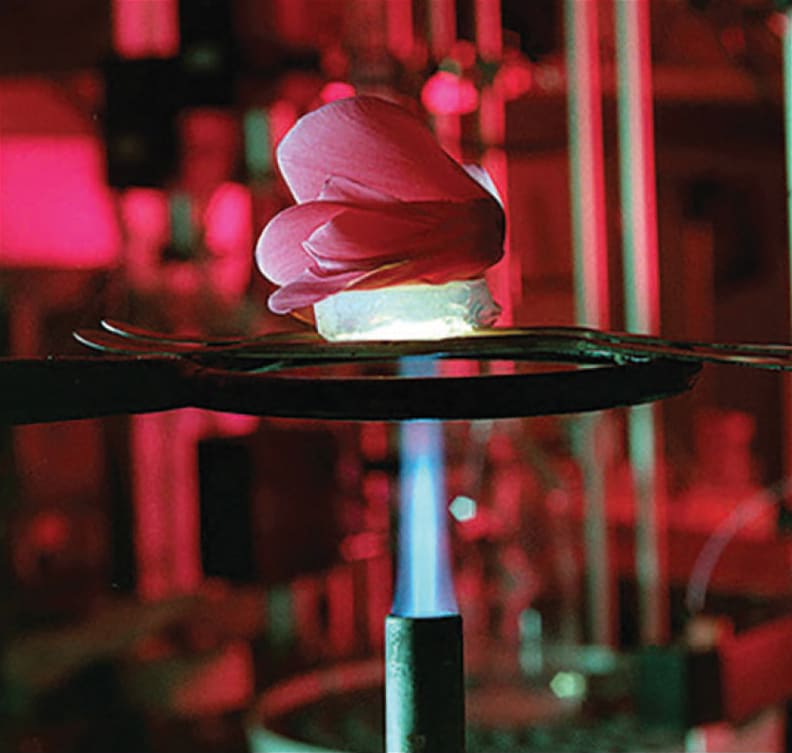

The material — silica aerogel — was first invented nearly 100 years ago, before NASA was founded. Aerogels are a class of materials made by creating a kind of gel and then removing all the liquid through a process known as supercritical drying, leaving a porous solid filled with air. When made out of silica, or fused quartz, the resulting material has pores less than 1/10,000 the diameter of a human hair, or just a few nanometers. That nanoporous structure gives silica aerogel the lowest thermal conductivity of any known solid, which means it's an incredibly good insulator, and because the structure is 95 percent air, it is also extremely lightweight.

The possible applications for the material were obvious, but pure silica aerogel had a major downside. Silica, one of the key ingredients in glass, is brittle. As an aerogel, it would crack under the slightest pressure, so for decades, silica aerogel was hardly ever used.

In 1992, Kennedy Space Center mechanical engineer James Fesmire had an idea for a flexible aerogel insulator — a composite with the same ability to stop heat as traditional silica aerogel but one that would solve the brittleness problem. He wanted to use it to insulate the equipment that stored and transferred liquid fuel for the Space Shuttle, which needed to be kept at temperatures hundreds of degrees below zero.

The following year, Kennedy awarded a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contract to Aspen Systems Inc. to work on creating that flexible, durable, easy-to-use form of aerogel. The company developed aerogel composite blankets that fill the spaces of a fiber web with silica aerogel. Aspen saw that it had a marketable product and spun off a division called Aspen Aerogels Inc. to sell its flexible aerogel commercially. The material found a home in many applications outside the space industry, including building and construction, appliances and refrigeration equipment, and more.

All of this happened well before Markesbery summited in Switzerland, but he didn't find out about aerogel until several years later, when he won a scholarship from the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation for his undergraduate research. As part of the award, he met astronaut Robert Gibson, from whom he finally learned about the material. The scholarship also came with $10,000, which he and his partners combined with their own money and began working with different aerogel manufacturers.

They ultimately came across Aspen Aerogels, launched a Kickstarter campaign, and started selling Oros's first product: the Lukla jacket, insulated with Aspen's aerogel blankets. They quickly raised more than $300,000 and sold more than 1,100 jackets, all featuring the aerogel blankets developed with NASA funding.

Oros boasted customers could wear a Lukla jacket “with no layers and be perfectly warm in even the most extreme temperatures,” thanks to its NASA-tested and approved aerogel insulation. When they made the original jacket with the aerogel blankets, they learned that they were amazing insulators and good for apparel, but not great. The silica tended to flake out of the fiber blanket with movement — a problem for a jacket intended for athletes. The silica aerogel itself also tends to suck out moisture on contact, so it would dry out the skin. That meant the insulation had to be encapsulated, which cut the breathability down to virtually zero.

The company came up with a proprietary way to use aerogel in a flexible polymer composite, which provides more structure and stability than the fiber blanket. It also increases breathability for comfort and reduces the overall weight of the insulation. As a result, the next-generation jacket is at least 40 percent lighter than the original, weighing in at just 2.5 pounds or less. The proprietary insulation, called SolarCore, is used in its jackets, gloves, leggings, snow pants, and base-layer shirts. Oros claims the insulation is so warm, it has added zippered vents in the jacket and snow pants in case the wearer overheats — all with just 3 millimeters of insulation.

Visit here .