With just a 50-million-electron jumpstart, sensors can power themselves for more than a year.

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis, led by Prof. Shantanu Chakrabartty, created self-powered sensors by taking advantage of a quantum effect known as "tunneling."

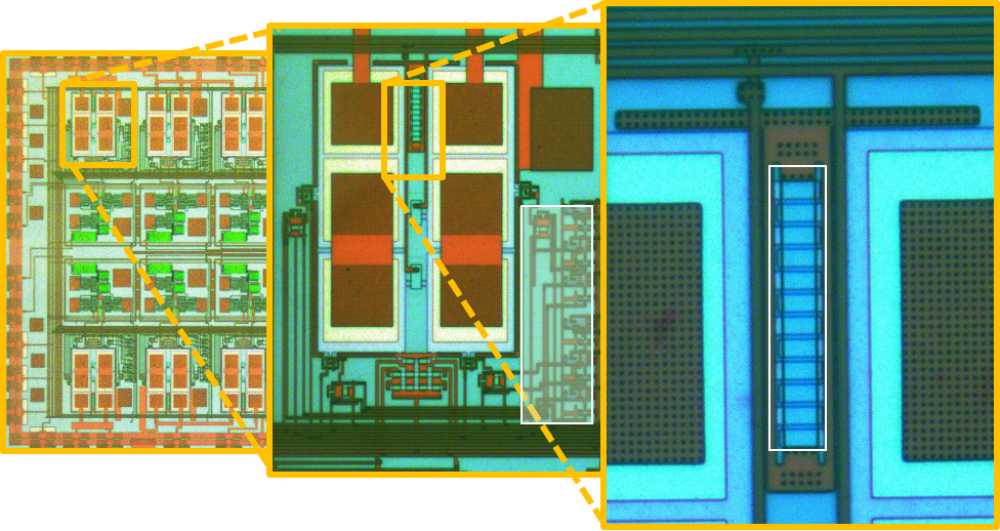

For a device that relies on complex physics, the sensor is somewhat simple. The components required are four capacitors and two transistors.

From these six parts, Chakrabartty’s team built two dynamical systems, each with two capacitors and a transistor. The capacitors hold a small initial charge, about 50 million electrons each.

The 50 million electrons are programmed in during the device initialization phase.

The devices also contain a kind of tiny dividing blockade. Less than 100 atoms thick, the "Fowler-Nordheim tunneling barrier" is positioned between the plate of a capacitor and a semiconductor material. The sensor is able to power itself for long periods of time by adjusting the boundary to better control the flow of electrons.

"You can make it reasonably slow, down to one electron every minute and still keep it reliable,” said Chakrabartty.

At that rate, the dynamical system runs like a timekeeping device — without any batteries — for more than a year.

To measure ambient motion, a tiny piezoelectric accelerometer was connected to the sensor. Researchers mechanically shook the accelerometer; its motion was then transformed into an electric signal.

The signal changed the shape of the barrier, which, thanks to the rules of quantum physics, changed the rate at which the electrons passed the barrier.

To put it more simply, the electrons didn't go over the barrier. They tunneled right through it.

The probability that a certain number of electrons will tunnel through the barrier is a function of the barrier’s size. It's a bit like an hourglass, Chakrabartty told Tech Briefs.

Each of the 50 million electrons is like a grain of sand, pouring through the tunneling barrier. The transducer signal controls the diameter of the narrow tube. So, when a large signal is transduced, the tube enlarges and more electrons pour through the barrier.

"By measuring the total 'sand,' or electrons, remaining in the upper chamber (after a certain period of time), we can estimate the total average energy of the transducer signal," said Chakrabartty.

After the experiments, the research team read the voltage in both the sensing and reference system capacitors. They used the difference in the two voltages to find the true measurements from the transducer, and to determine the total energy that was generated by the sensor.

“Right now, the platform is generic,” Chakrabartty said. “It just depends on what you couple to the device. As long as you have a transducer that can generate an electrical signal, it can self-power our sensor-data-logger.”

The team hopes to someday use the sensors for a variety of applications, like recording neural activity or monitoring glucose levels inside the human body.

In a short Q&A with Tech Briefs below, Prof. Chakrabartty reveals his ideas for the self-powered technology.

Tech Briefs: Simply speaking, how are you able to get a sensor to run for a year, with only a small initial energy input? Is it about controlling the flow electrons?

Prof. Shantanu Chakrabartty: Yes, its all about controlling the flow of electrons. We initially program about 50 million electrons on a floating-island. Then by exploiting Fowler-Nordheim (FN) quantum tunneling we control the rate at which the electrons leak out from this island. In this case the electron leakage rates are in the range from a few electrons per second to 1 electron per minute. The interesting concept in this work is how the physics of FN tunneling ensures that two devices can be matched even if the electrons are leaking out at such a slow rate.

Tech Briefs: I want to focus on this small initial energy input — what’s required to pull the apple off the tree, so to speak? What is that “small initial energy input?” Where is it coming from, and how much is required?

Prof. Shantanu Chakrabartty: The initial energy is required to deposit the electrons on the floating-island. This can be done during manufacturing or initialization. For one device we are talking about an initial energy of only 10 picoJoules. Note that this energy is equivalent to the energy that needs to be dissipated to write one bit many memories. Once this initial number of electrons are deposited, the physics of quantum tunneling takes over and the device does not need extra energy to operate. All the energy for sensing comes from the transducer – like a glucose sensor or a piezoelectric sensor.

Tech Briefs: What are the biggest challenges in controlling that energy so that it effectively powers the sensor?

Prof. Shantanu Chakrabartty: The initial powering of the device is not a problem since once we are able to deposit the electrons, the device self-calibrates itself. The biggest challenge is in regards to sensing – that our device can pick up everything if that source can couple energy into our device. So sensitivity comes at a price but that is why we are using a differential architecture to compensate for environmental artifacts. The other challenge is the readout of the device – with only a few electrons tunneling across the barrier, the change in voltage that needs to be read out is in the order of microvolts.

Tech Briefs: What is the most exciting application, or applications, that you envision with this self-powered sensor?

Prof. Shantanu Chakrabartty: This is a platform technology so can be applied to broad range of sensing applications. However, at the power/energy levels we are reporting, a biological cell can now self-power our sensing device.

We have been trying to use these sensors to record neural activity in the brain of an organism, where the electrical activity inside the brain powers the device. That was the focus of the National Institute of Health research grant that originally funded this project.

So, in that regard, this device acts like a USB memory stick that gets plugged into the brain, which also acts as the source of power. We can have multiple copies of these devices (in fact, we can integrate a millions of them on a single chip) that sense and store the neural activity. The challenge that we have been trying to address is how to reconstruct the events after the chip has been retrieved and the stored information is measured.

What do you think? Share your questions and comments below.

Transcript

00:00:00 I'm dr. Shannon Chakraborty and this is adaptive integrated micro systems laboratory so in this lab we actually the designs they start from the whiteboard now where we start with equation you solve some models you simulate them and then we try to put these equations on these chips these chips are actually solving these

00:00:25 equations PhD students in this lab get an end-to-end experience which means that they start from a concept where they know that there is a fundamental problem that they need to solve that forms the part of the PhD thesis once they have formalized the problem and they look at something new in that domain then the goal is to apply it into the real world

00:00:50 my research in particular deals with understanding the noise and the variations in environment factors on the systems and its performance so research in a lab is not just limited to the theory and lab experiments but also translating most of the research into practice which requires actually for us to test some real-world conditions and

00:01:14 that's where we have this set up where we can actually simulate the temperature and humidity conditions and actually verify our chips in practice and then use our chips and deploying them anywhere we want so this not only helps us understand the performance of system and real-world conditions but also help us to understand how to design the systems before we actually approach in

00:01:37 making them right now I'm talking about some kind of timers which run without any batteries so they're like clocks but nomads it's basically you program it once and you leave it and when you again read the value it will have changed and that how much it has changed depends on how much time is elapsed I hope my research will do is replace both of these chips with one much

00:02:02 smaller chip which we can implant inside the brain of the locust and then seal it up I am working on a this Wireless no recording for a loop so basically what this is ideally you know allowed us to do is record these signals from this insect while it's moving in a mobile or deployment style environment and transmitted wirelessly back so the user can see it and hopefully make some sort

00:02:26 of informed decision about information originally the project that this started from is using Mesa has actually bomb detected so the locust is going to go in kind of explore of environment that would be potentially dangerous for humans and hopefully smell the explosives and collect the information and then transmit it back wirelessly we're adding sensors to produce such as

00:02:47 a Mackinac Bridge and we are collecting data self-powered and we don't require any battery power for this and we can collect a continuous stream of data and we can extract some sort of history of what the strain levels have been inside the structures the project itself is called electronic tools the goal of having this kind of electronic to it is to replace breaking the fingers in order

00:03:13 to get the blood to measure for example the amount of sugar inside the blood so the same thing is existed in the saliva in order for that electronic circuit to be functional it requires a power but nobody wants to have a battery inside of oral cavity we created this technology by delivering the power wirelessly we can get the data also using an antenna inside the room to measure that without

00:03:40 having any non convenient way to get the blood from the fingers or something like this you