A team at MIT has moved beyond traditional trial-and-error methods to create materials with extraordinary performance through computational design. Their new system integrates physical experiments, physics-based simulations, and neural networks to navigate the discrepancies often found between theoretical models and practical results. One of the most striking outcomes: the discovery of microstructured composites — used in everything from cars to airplanes — that are much tougher and durable, with an optimal balance of stiffness and toughness.

“Composite design and fabrication are fundamental to engineering. The implications of our work will hopefully extend far beyond the realm of solid mechanics. Our methodology provides a blueprint for a computational design that can be adapted to diverse fields such as polymer chemistry, fluid dynamics, meteorology, and even robotics,” said Lead Researcher Beichen Li.

In the vibrant world of materials science, atoms and molecules are like tiny architects, constantly collaborating to build the future of everything. Still, each element must find its perfect partner, and in this case, the focus was on finding a balance between two critical properties of materials: stiffness and toughness. Their method involved a large design space of two types of base materials — one hard and brittle, the other soft and ductile — to explore various spatial arrangements to discover optimal microstructures.

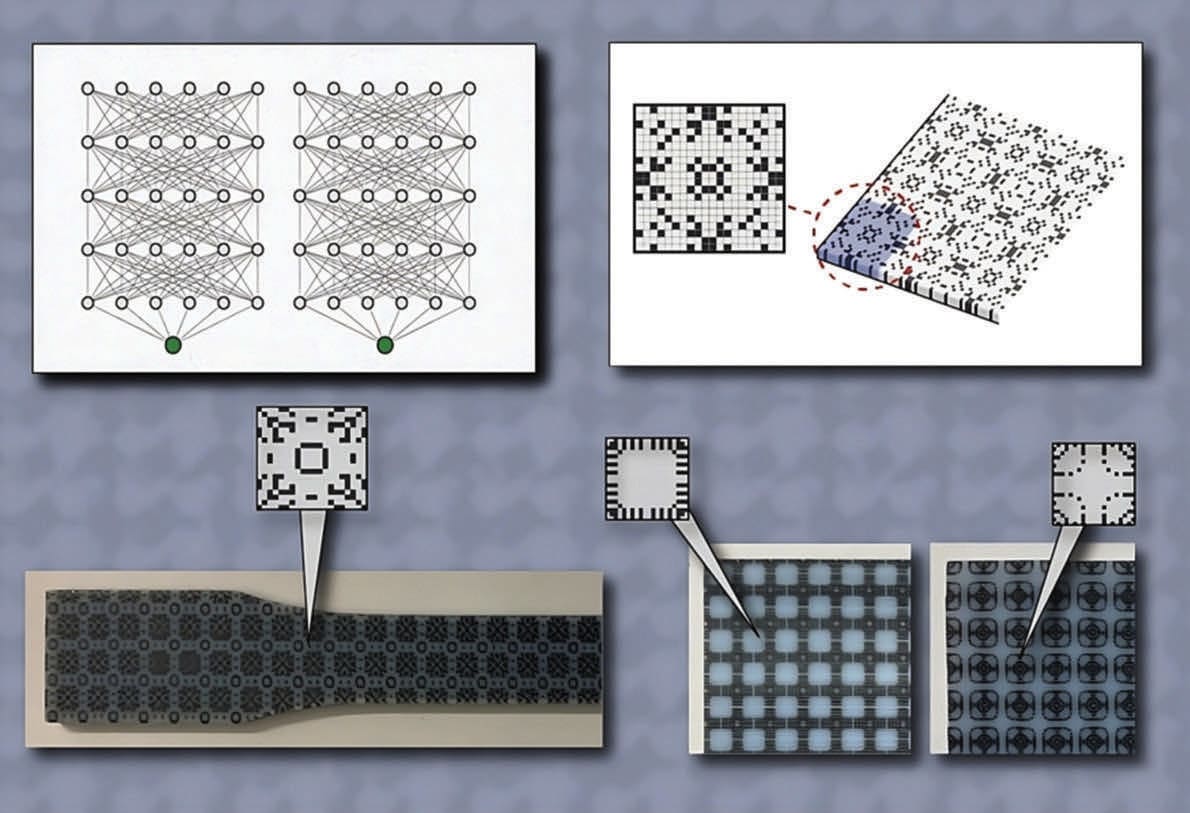

A key innovation in their approach was the use of neural networks as surrogate models for the simulations, reducing the time and resources needed for material design. “This evolutionary algorithm, accelerated by neural networks, guides our exploration, allowing us to find the best-performing samples efficiently,” said Li.

The team started its process by crafting 3D-printed photopolymers, roughly the size of a smartphone but slimmer, and adding a small notch and a triangular cut to each. After a specialized ultraviolet light treatment, the samples were evaluated using a standard testing machine — the Instron 5984 — for tensile testing to gauge strength and flexibility.

Simultaneously, the study melded physical trials with sophisticated simulations. Using a high-performance computing framework, the team could predict and refine the material characteristics before even creating them. The biggest feat, they said, was in the nuanced technique of binding different materials at a microscopic scale — a method involving an intricate pattern of minuscule droplets that fused rigid and pliant substances, striking the right balance between strength and flexibility. The simulations closely matched physical testing results, validating the overall effectiveness.

Rounding the system out was their “Neural-Network Accelerated Multi-Objective Optimization” algorithm, for navigating the complex design landscape of microstructures, unveiling configurations that exhibited near-optimal mechanical attributes. The workflow operates like a self-correcting mechanism, continually refining predictions to align closer with reality.

As for the next steps, the team is focused on making the process more usable and scalable. Li foresees a future where labs are fully automated, minimizing human supervision and maximizing efficiency.

“Our goal is to see everything, from fabrication to testing and computation, automated in an integrated lab setup,” said Li.

For more information, contact Rachel Gordon