People with diabetes rely on continuous glucose monitors to keep track of their blood sugar, but eventually the monitor's batteries need to charge. The same is true for a pacemaker or any mobile device, like a fitness tracker. And batteries are bulky and require regular maintenance.

To free wearable tech from these burdens, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University's School of Computer Science developed Power-over-Skin, which allows electricity to travel through the human body and could one day power battery-free devices from head to toe.

"We can expect all our electronics to keep improving," said Andy Kong, part of the team that developed Power-over-Skin. "New releases, such as smartwatches and glasses, will be able to do so much more, but it will always be difficult to get electronics onto the body because people have to think about charging them. Power-over-Skin opens the door to making these devices invisible, allowing them to do their jobs without you noticing, which is how health monitoring should work."

Still in its early stages, Power-over-Skin allows researchers to design and implement new methods of transmitting power frequencies through the human body. In the study, researchers powered small objects like LED lights, but they envision powering smart glasses or other wearables in the future.

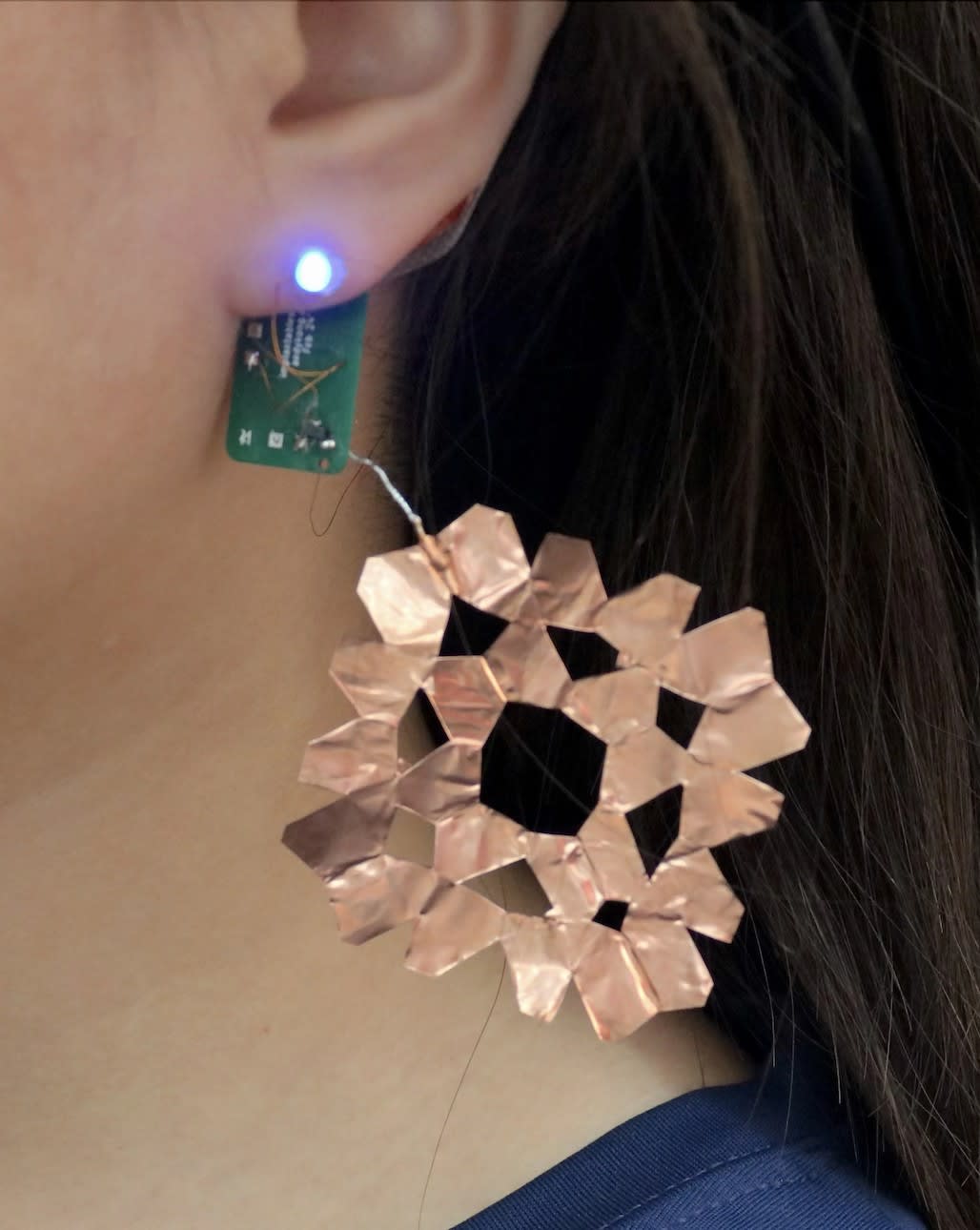

Kong, who earned his bachelor's degree from SCS and returned to the Human-Computer Interaction Institute (HCII) to work on Power-over-Skin in the Future Interfaces Group, said commercially available health-monitoring devices are often placed on the wrist, hand or chest for convenience and to accommodate easy removal. Without a battery, a small health-monitoring device could be embedded into something as unobtrusive as an earring.

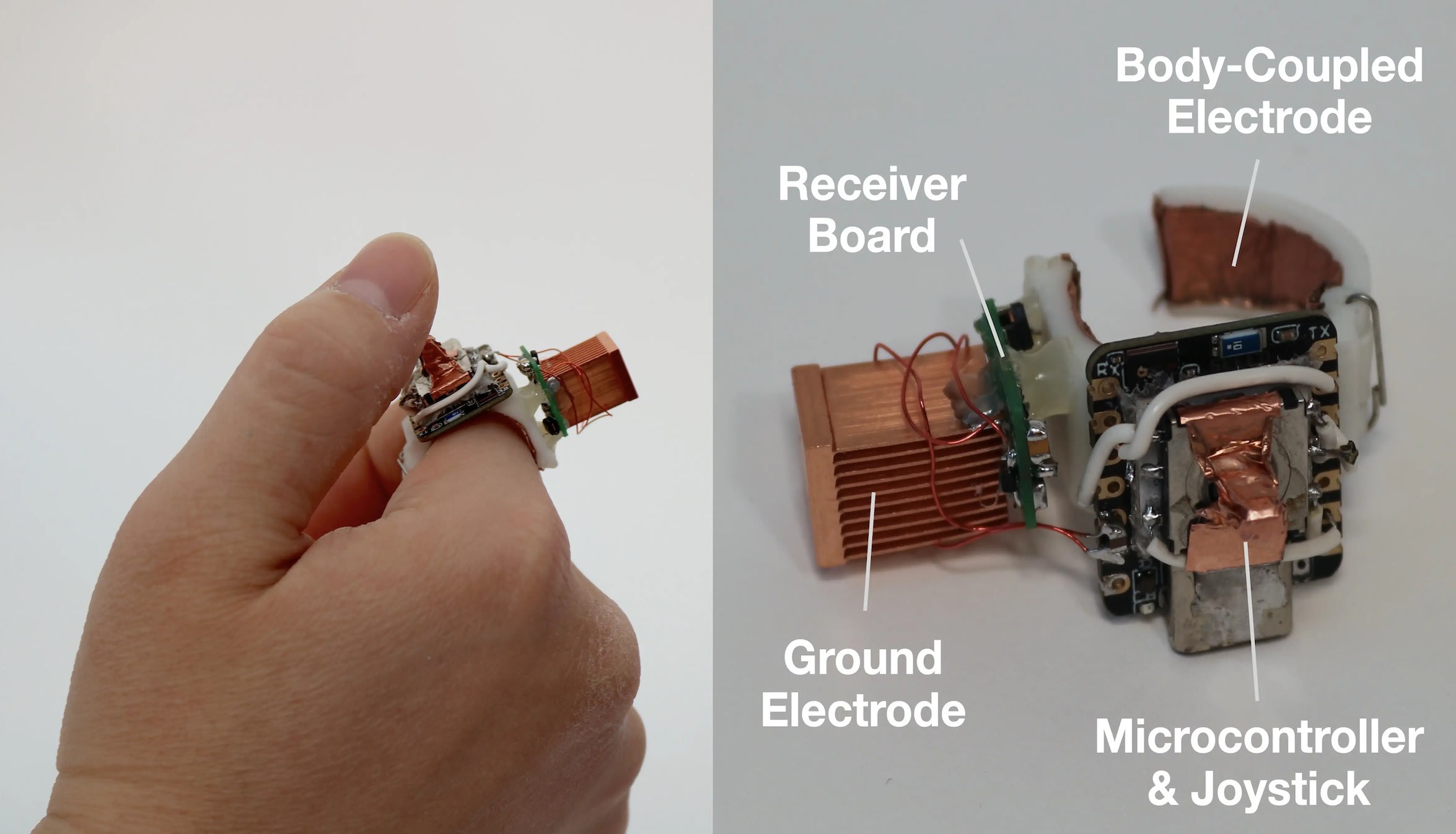

Kong worked with HCII Associate Professor Chris Harrison and doctoral student Daehwa Kim to develop Power-over-Skin. Prior work demonstrated that the human body can efficiently transmit 40 MHz radio frequency (RF) without losing too much power to the air. The CMU researchers used a single battery-powered transmitter that's worn on the body to send power to receivers — objects like a Bluetooth joystick embedded into a ring and a light-up earring. While study participants wore these devices in locations ranging from the wrist to the ankle, researchers noted a correlation between the power the devices received and their distance from the transmitter. The closer the transmitter, the more power a receiver got.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Kong.

Tech Briefs: What was the catalyst for this project?

Kong: Power-over-Skin was inspired by my frustrations with charging multiple devices — I had accumulated earbuds, phone, laptop, and a smartwatch, all of which required daily or weekly maintenance. And while charging is not difficult, I thought that the convenience of the new devices (airpods vs wired earbuds, smartwatch vs casio watch) came at a hidden cost of unreliability (sometimes they're dead, when the older generation of devices could last years).

At the time I was working on wireless power transfer, using RF transmitted through the air. This requires base stations to be installed everywhere you would want to use the power, which I thought was unscalable. Around this time I discovered Prof. Jiamin Li's excellent nature paper using the skin as a medium to transfer a little bit of power, and wanted to see if I could improve it. In this case, all we'd have to do is add a single base station to the body, and all devices I touched would be able to get power off of that. This was how I wanted devices to operate in the future, so I did an initial replication and started improving it.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how Power-over-Skin works please?

Kong: The nearest technology to Power-over-Skin is radio. For instance, when a car receives radio waves, the station is miles away. Using a powerful transmitter and by picking a frequency that travels well through air, it is able to send audio data through the air from their station antenna to your car antenna, which gets boosted and played as audio.

Power-over-Skin is similar, except instead of picking a frequency that travels well through air, we pick one that travels well through the body. The transmitter is powerful and must use a battery, but because the transmitted signal is so strong, the receiver actually doesn't need its own battery, and can instead directly use the power that it sees from contacting the skin.

If this is still confusing, there's a one-minute segment of my talk which is pretty informative:

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing Power-over-Skin?

Kong: The biggest challenge was in optimizing and refining the power transmission path. Unlike radios and air, the body is not good at transmitting electrical signals. It heavily attenuates them. Because of this, if the transmitter puts out 100mW, we would be happy to see 100uW on the receiver side. And since there is a recommended limit for how much RF power that a human body can be exposed to, the challenge becomes what signal waveform should we send to maximize power transfer from the transmitter, and what tricks can we use on the receiver to amplify a signal when we have no power.

Because the human body is so hard to model accurately, RF simulation software has limited use, meaning most of the optimization testing had to be done by hand. To try multiple configurations of matching networks, I had to go to the workshop, desolder and resolder a sub-millimeter component, then go back to the testing bench to see the effect. This was very slow.

Another challenge was measuring our power transmission without disturbing the circuit. Usually in electronics, one uses a multimeter or oscilloscope to easily read voltages and debug circuits. However, in our circuit, adding a probe noticeably improved the performance, because adding any conductor increased the power coupling between the receiver and transmitter. Coming up with a new way to measure without affecting the device was a surprise we had to deal with to make real improvements on the circuit.

Tech Briefs: What are your next steps?

Kong: 10x-ing transmitter power would really extend applications beyond simple trackers, but requires a large engineering effort on the RF side of things. Since there are people who are good at this and I am not, this would take an inordinate amount of time so there aren't currently plans to do this.

An effort which I'm more interested in is sending both power and data over the skin. We're currently using Power-over-Skin to transmit sensor data with a Bluetooth antenna — this costs a lot of energy every time we turn on the device. If we could instead send this data back over the skin, we save a lot of energy on communications and could double our energy budget for sensing or for outputs like audio / LEDs. It's also pretty elegant to send everything just over the skin.

We've made initial prototypes for this but need more time to work on decoding this data.

Transcript

00:00:03 hi my name is Andy Kong uh today on behalf of my co-authors Chris and DEA I'd like to present our work power over skin advances in electronics have enabled small yet powerful wearables for health and entertainment applications uh but despite these advances batteries haven't evolved nearly as quickly uh and they still contribute a lot of the bulk and the weight in these

00:00:22 wearables um the effects of this are twofold one is that existing devices are kind of big like this ring I think is kind of chunky compared to a normal ring uh since they have to carry all their power with them uh and secondly it precludes certain wearable form factors such as health sensing patches or jewelry these don't really exist commercially um because of the

00:00:39 difficulty of incorporating a battery uh so let's cancel batteries what can we do instead to power these wearables so one idea is you already carry around devices with batteries such as your phone or your Smartwatch how can they share this power with little devices uh and this isn't such a pipe dream right the older generation should recognize that um wired headphones are

00:00:58 an example of passive devices that share power from our larger devices um but if you have multiple devices wires are pretty unfeasible what what's the alternative how else can we do this so we draw inspiration from the field of body area networks so these find that high frequency electrical signals can pass through the body pretty easily uh they use this to transmit data between a

00:01:17 transmitter and a receiver but why not turn it up a notch let's also send power we've envisioned a future where you can incorporate an RF transmitter in an existing device like a phone um this couples RF energy into the body uh empowers a network of battery-free wearable devices for all sorts of applications uh so a bit of background on this technique you know we're not the

00:01:37 first to think of it uh these are the existing papers in the field uh and they're all pretty similar they use the skin as a wire to pass RF energy between a battery powered transmitter and battery-free receiver devices but they also have an issue uh wearables need certain traits from their power source right they need high enough power to do sensing and communication they need this

00:01:56 power to be accessible at different parts of the body and they need to be small or else you would just use a battery instead but the existing approaches only let you pick two of these features that are critical and wearable devices in light of this I'd like to introduce our work power over skin full body wearables powered by inbody RF energy we achieve a very small

00:02:14 receiver size uh which is capable of harvesting enough power over the skin to run a microcontroller and sensors and we can uh reach this power across most of the body so how does this work uh the skin is slightly conductive and especially so at higher frequencies if you look at the skin transmission efficiency graph you'll see a peak around 40 MHz this means that if you're

00:02:34 touching a transmitter that's going at 40 MHz it will fill the body pretty evenly you can see from this guy he's you know fully red then it's just a matter of harvesting this power uh for the details of how we implemented it I'm going to walk you through the same way the power path goes from the transmitter to the skin into the receiver so we'll start with the transmitter the

00:02:53 fundamental question is what kind of waveform do you use for transmitting power and sure the you know the graph just says 40 MHz you can make a sine wave and just couple it right into the body uh but if you look at the graph closely there's actually a range of frequencies which work right anywhere from like 40 to about 100 MHz uh and just because the gain is lower doesn't

00:03:09 mean that you can't transfer any power and so part of our paper is we propose using a different waveform such as square waves which are able to send multiple harmonics of this fundamental frequency allowing you to send multiple signals at the same time and you can get more out of this curve than you would with just a sine wave for instance in our testing we found that square waves

00:03:28 actually transmit 75% more power than sign waves for the same peak-to Peak voltage but that's not the only cool part of using square waves you can also generate them really easily using a microcontroller uh because they all have a clock signal you can just ask them to Output this clock on one of the pins and boom you have a square wave put it through an amplifier and you just couple

00:03:46 it into the person so that decides our transmitter wave form 40 MHz Square wave but there's another issue once you get to the skin interface so higher energy rfes actually doesn't really like going into the body uh some of it will bounce because your impedances aren't matched between the the skin and your amplifier so one thing you can do is you can make an LC circuit which impedance

00:04:05 matches the uh the amplifier in your body and then it allows you to preserve your transmission efficiency so once the energy enters the body what happens on the receive side so all the receivers that you're wearing will see a very attenuated waveform this is because the body actually doesn't really like transmitting power you're kind of making it do it um and this is

00:04:24 an issue for us because when you actually Rectify an AC signal you have to use a diode and this incurs a voltage Vol drop if you already have a very small voltage you incur a voltage drop you end up with almost no power so one thing you can do on the receive side which is really clever this is proposed by Lee at all in nature um you can use an LC circuit which is matched to your

00:04:44 transmitter waveform uh and it passively boosts the voltage of your transmitted signal on the receive side and this is without using any power uh and it comes at a cost of like you know the reduced current but it allows you to get more power out of the Skin So after this is it's pretty simple we Rectify it into DC voltage and then store it in our capacitor and once you have the power on

00:05:03 the receiver you can use it for anything uh we do Communications we do Bluetooth we've run sensors we do computation we take input we've run a display um but I'm not going to leave it all for you guys to figure out uh we made some Dem demo apps to show you what we can do with this thing uh so our initial prototype was a blinking LED very simple just to show that we had power uh and we

00:05:25 used this to debug how much power we were getting and this is blinking entirely off of Power harvested from body contact uh we later repurpose this into a light up earring and you here you can see it so the ground plan is decorative here it's used as like a little snowflake pattern uh and the power comes in through the ear contact but this is just an LED you know like

00:05:45 what else can we do so for a more complete example we took this calculator and just butchered it we took all the power sources out of it we removed the solar panel and then we put our receiver in this is the only power source on this calculator and you'll see I'm wearing a transmitter on my left arm uh which is out of frame but as soon as I I touch the calculator you'll see that it powers

00:06:01 on and this is because it's harvesting the energy uh from through my body contact and this demonstrates input output and computation in this commercially available device U but let's do some more connected stuff so we were also able to incorporate this into a ring controller uh so this is a 32 MHz microcontroller uh full Bluetooth stack and has a joystick and so it allows the

00:06:23 user to send in real time commands to their devices and it's powered entirely over the skin so here's a of it working on a TV we envisioned that not only can you control a TV but you can incorporate this transmitter into something like a VR headset uh and you can have the headset power its own controllers just over the skin uh and then you don't need to charge two

00:06:44 devices for lower energy applications we also made a really slow Bluetooth thing so this is a thermometer it measures someone's core temperature uh it's a little patch thing and it sends this data to a laptop or a phone every five minutes or so uh I almost always have one of these demos on me so if you want to see it in action just come find me and I'll also be at demo night tonight

00:07:05 so you know I'll be around so once we decided the implementation of our our thing uh we wanted to test you know what conditions does this really work in how much power can we expect out of this thing uh so here's some of our evaluation experiments we actually test a lot of things so you should check out our paper for more more details I couldn't fit it

00:07:21 all in here so the first question is you know how much power can you actually get I said 40 MHz goes well and then I said it attenuates you know what are we looking at so prior works stated that like power Falls exponentially with on-skin distance exponentially fall off it's pretty bad for power uh and we found this also to be the case uh when we tested on the arm but weirdly we saw

00:07:42 you could still transmit power from arm to arm you could get it you know from one side of the body to the other so it wasn't exactly linear with unbodied distance and since it was such a complex thing we ran an empirical study with a bunch of people you know to figure out depending on where you put the transmitter how much power can you get at each receiver location

00:08:00 uh so we picked a couple of transmitter locations that are that we expect you to already have devices that have batteries uh or that won't mind the weight of adding a battery for instance the head is where a headset might go the wrist for your Smartwatch the pocket for your phone uh on the waist and in your shoe so these are our transmitter locations and then we found some receiver

00:08:19 locations that would be nice um are difficult to fit a battery due to size constraints or that they're just well spread out on the neck the hand and the chest and then we cross them every transmitter and every receiver were tested separately and we measured how much power is available and we generated these nice heat Maps uh so this allows us to figure out you know if we put the

00:08:39 transmitter on the wrist how much power can we expect on the arm and this sort of thing um the thing I want to draw your attention to is the right figure so this is the left pocket transmitter and what's neat about this is that it's almost the same color as all the other heat Maps which means that the power transfer is about the same you see they they share a scale uh this is neat

00:08:57 because this transmitter isn't even touching you this transmitter we actually just put in the participants's pocket uh and it couples through clothing uh which was which is pretty neat because it allows you to be more loose with how you how you implement this into existing devices so pretty cool another thing we wanted to test was since the effect is capacitive do you

00:09:14 really need electrodes uh all the PRI workor that we could find used either metallic electrodes or wet electrodes that's not like super nice and so we were curious if it would work with any conductive stuff we got everything conductive I could find in the lab which is a smattering of different materials here's copper on the right right this is a received power using a copper

00:09:32 electrode versus all the other ones you see that a lot of them transfer power just as well uh and many of these are off fabrics and rubbers which is pretty neat because it means that you know you don't need to have exposed contact like this for it to work and the last question is you know does it scale we made a ton of devices and you know we say we envision a network of receivers

00:09:51 um does it actually work on a bunch of them so what we did was we got someone's hand uh and we got a bunch of receivers and we added one at a time and then measured how much power is available uh on the on the limb uh and here's what we find so there's a bit of a linear falloff this is just measured on one receiver uh so actually what you find is that you know they do share a power pool

00:10:09 so there's a bit of a fall off and interference pattern between each of them um but it falls off pretty slowly and it's not Zero Sum right the power is shared and in total more power is transferred because each of these gets to access the same amount of power and this is test is also a bit against our favor since they're on the same limb normally you would have them

00:10:27 shared just across the whole body uh and then hopefully they would interfere less so you know it's not perfect um I really like this project but you know there's some there's some drawbacks I think the main drawback is we actually don't get uh massive amounts of power uh we have a reasonable amount of power which is better than nothing um but only compared to Prior approaches so here's

00:10:49 some typical devices that you might have seen before um the earbud is the only wearable here all in the low Watts or high mwatts uh here they are on a log powered chart and here I power of skin uh so you see it's about an order of magnitude lower than earbuds but I argue that this actually is pretty competitive because they're existing devices that you may already be wearing such as a

00:11:10 glucose monitor or a fitness tracker which use much less than this amount of power uh and we're able to get this entirely over the skin and we're fighting against devices that have batteries in them so I think it's a pretty usable amount of power still another issue is that the body proximity affects delivered power so you see here the chest is a bit lower than the left

00:11:27 arm even though it's closer to the transm what's up with that um since the effect is capacitive there if the same signal couples into both the body electrode and the ground electrode then you reduce how much power you get after you harvest it uh this is a problem because it means you have to design the ground plane so that it sort of hangs away from the body for instance this

00:11:45 earring is perfect because you know the earring is always hanging uh but in certain other applications it might be harder to find a place to put it and the last question I want to answer is you know is this safe every time I tell people about this they're like you know like is is this good right so so uh the I read the I pretty extensively read the guidelines for this and uh the only

00:12:04 problem comes from heating so as this passes through you it attenuates a little bit your body picks up that heat right um the at our frequency it's recommended for an average person to have the total power be under five Watts our transmitter uh even our benchtop transmitter cannot get within 10% of that so at least in our implementation this is entirely safe so I'd like to

00:12:23 conclude now um we Advanced the state of the art and how much power and how far you could transfer uh inbody Power using several RF optimizations which are detailed in the paper we then conducted a bunch of experiments some of them being materials testing or power budget at different locations to characterize our implementation for reproduction and also to made several demo apps uh

00:12:43 showcasing potential use cases for this we look forward to the future of wearable battery free devices and now I'd be happy to take any questions thank you Andy so yeah it's a great presentation and personally I'm also doing something about electr tcto is also releasing power to the skin so I wonder you gave us a lot of parameter about the power

00:13:14 but how about the voltage because I knew like the voltage above like 100 volt or 200 volt you can feel this like it will pass through your Surface game so whether like can you give me more sure what kind of frequencies are you working with like like I'm working with DC DC like so at high frequency RF your body like the water is too slow reacting so you

00:13:34 actually don't feel anything it effectively is charge neutral um at 40 MHz especially there like no one has ever reported anything uh and it's too high of a frequency to really be felt as like individual uh stimulation so even though the voltage is like we've used like 20 volts in the past it's sort of more characterized in how much power you can transfer oh I see

00:13:55 s hi I'm Rio from Tokyo University so thank one nice talk so I have two question so one is uh what is uh different from the nature Electronics one and second one is the robustness of nearby metallic item so now you are standing near the metallic table so what is the robustness so this frequency passes very well through the body uh actually if you

00:14:23 pack in multiple body so if you're testing this uh and somewhere in between the transmitter and the receiver there's another person some of the power will be leaked over to the other person uh we haven't found a lot of interference from like really large metal objects but you know we've been using I I didn't characterize this specifically and I forgot your first question so if you

00:14:40 could remind me thanks so Al one question is what is the different from the nature Electronics paper Okay so the nature paper was fantastic I really enjoyed reading it uh but they were not able to get nearly enough power from uh across the body ranges I think they got like two mic from head to toe uh so we increased the

00:15:01 power delivery using Square wave uh waveform and we also did other RF optimizations okay thanks um and for the sake of time Ean if I can ask you to start setting up um we have one more talk after this we started a bit late and then our last question uh thank you so much for the very cool presentation uh Mara from mitc sale um so you mentioned how you have to

00:15:28 use like an LC circuit to impedance match I was just wondering if that impedance matching had to change between one participant to another and if there's sort of like a way to dynamically adjust that uh so we refer to some work uh done by I forgot who it was but it said in our paper at really high R frequencies the impedances sort of converge uh so our one LC circuit

00:15:51 worked for most part participants pretty pretty much the same I think the impedances are off by like 30 or 40 ohm so it was pretty closely match just like matching to the center of all the participants from the P that we cited okay thank you Andy [Applause]