Snap a photo of your meal, and artificial intelligence instantly tells you its calorie count, fat content, and nutritional value — no more food diaries or guesswork.

This futuristic scenario is now much closer to reality, thanks to an AI system developed by NYU Tandon School of Engineering researchers that promises a new tool for the millions of people who want to manage their weight, diabetes, and other diet-related health conditions.

The technology, detailed in a paper presented at the 6th IEEE International Conference on Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics, uses advanced deep-learning algorithms to recognize food items in images and calculate their nutritional content, including calories, protein, carbohydrates, and fat.

For over a decade, NYU's Fire Research Group, which includes Lead Author Prabodh Panindre and Co-Author Sunil Kumar, has studied critical firefighter health and operational challenges. Several research studies show that 73-88 percent of career and 76-87 percent of volunteer firefighters are overweight or obese, facing increased cardiovascular and other health risks that threaten operational readiness. These findings directly motivated the development of their AI-powered food-tracking system.

"Traditional methods of tracking food intake rely heavily on self-reporting, which is notoriously unreliable," said Panindre, Associate Research Professor of NYU Tandon School of Engineering’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. "Our system removes human error from the equation."

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Panindre and Kumar.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing this AI food scanner?

Panindre: One of the greatest challenges was overcoming the inherent variability of food presentations. In contrast to manufactured objects with consistent appearances, food items vary enormously in shape, color, texture, and presentation. For example, the same dish can look dramatically different depending on preparation or even cultural context. This variability posed two major technical hurdles:

- Visual Diversity: Food items in real-world images display staggering visual diversity. To tackle this, we developed a robust preprocessing pipeline and a series of algorithms to standardize and balance our dataset.

- Accurate Portion Size Estimation: Converting a 2D image into a reliable nutritional assessment requires accurately estimating portion sizes. This was addressed by our volumetric computation function that calculates the exact area each food occupies on the plate. By correlating these areas with density and thickness data from the nutritional database, we were able to convert image measurements into meaningful nutritional values.

Tech Briefs: Can you please explain in simple terms how it works?

Kumar: Step 1 is image capture and preprocessing: When you snap a photo for your meal with your smartphone, the system first standardizes the image — resizing it, converting it to the correct color format, and normalizing pixel values — so that it fits the requirements of our AI model.

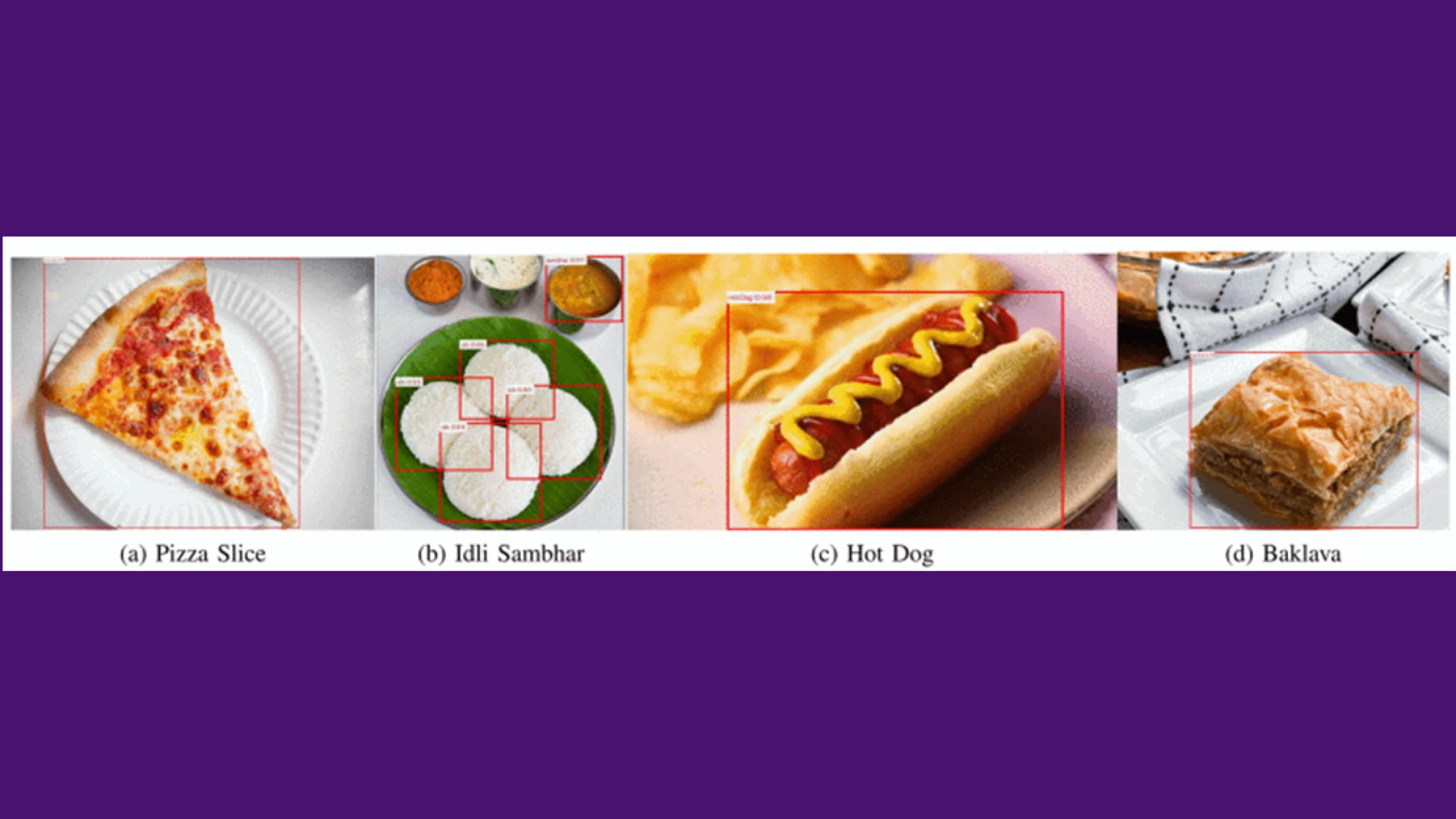

Step 2 is food recognition: The processed image is then fed into an AI model that has been trained to detect and classify various food items. The model identifies each food item by drawing bounding boxes around them.

Step 3 is portion and nutritional analysis: For each detected item, the system calculates the area it occupies on the plate. This area, combined with known density and thickness values from a nutritional database, allows the system to estimate the volume and weight of the food. From these measurements, it computes nutritional information such as calories, proteins, carbohydrates, and fats.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research/work/etc.? If not, what are your next steps?

Panindre: We plan to enhance our model by further augmenting our training dataset. This involves incorporating more images — especially for underrepresented or challenging food categories — to improve the model’s accuracy and generalization across even more diverse cuisines.

In addition, we are planning to develop a dedicated large language model (LLM) that will work synergistically with our current computer vision framework to interpret complex dietary data, extract relevant nutritional information from diverse sources, and generate personalized, conversational dietary recommendations.

While the current system is designed for dietary tracking, we envision its adaptation to broader health management scenarios. For instance, integration with personalized health apps and wearable devices could allow for real-time monitoring of dietary impacts on conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

We are also looking into incorporating user feedback and real-world usage data to continuously refine the system’s usability and accuracy. This may involve developing a dedicated mobile app to offer personalized nutritional recommendations.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Kumar: The broader implications of our work extend beyond individual dietary tracking. With obesity and related health conditions on the rise globally, tools like this could play a critical role in public health initiatives by providing accurate dietary data and enabling targeted interventions.

By integrating the AI models within the app, we have also addressed privacy concerns — processing can occur locally on a device without the need for sending sensitive data to cloud servers. Moreover, it has allowed us to achieve significant improvements in computational efficiency, making real-time analysis a reality.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any advice for researchers aiming to bring their ideas to fruition (broadly speaking)?

Panindre: Balance innovation with practicality; embrace interdisciplinary collaboration; focus on robust data preparation; iterate and validate in real-world settings; and finally, be prepared for unexpected challenges!