Solar cells account for approximately six percent of the electricity used on Earth; however, in space, they play a significantly larger role, with nearly all satellites relying on advanced solar cells for their power. That’s why Georgia Tech researchers will soon be sending 18 photovoltaic cells to the International Space Station (ISS) for a study of how space conditions affect the devices’ operation over time.

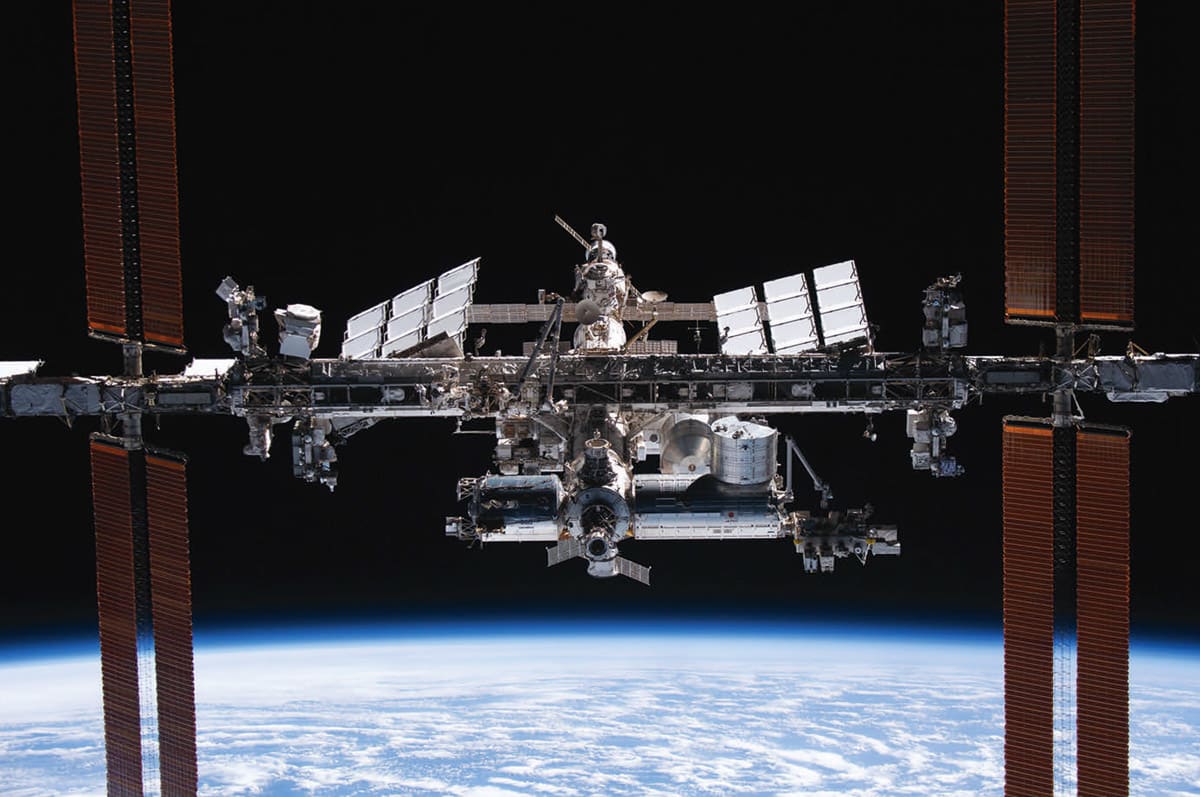

To be installed in the Multi-purpose International Space Station Experiment (MISSE) Flight Facility on the exterior of the ISS, the cells will be studied over a six-month period, providing researchers with detailed information on factors affecting their operation in the harsh conditions of space. Among the goals are to obtain data useful for reducing weight and boosting both efficiency and reliability of the devices.

The devices under test will include halide perovskite-based cells, a likely materials platform for next-generation solar cells. Composed of a combination of materials that can be varied according to conditions, halide perovskites differ from the gallium arsenide (GaAs) family of materials commonly used in space — and from the silicon cells common for use on Earth. Which perovskite recipe works best in space applications will be among the questions the Georgia Tech researchers hope to answer.

The test cells will also include silicon-based devices, photovoltaic cells based on III-V materials — so-called because they utilize combinations of materials from the third and fifth rows of the periodic table of the elements — and infrared photodetectors designed for use in space.

“The main goal here is to improve power generation in space,” said Jud Ready, Principal Research Engineer at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) and Executive Director of Georgia Tech’s Space Research Institute. “The limiting factor on the performance of a spacecraft is usually how much power you can produce. Power, size, weight, complexity, cost — all of these are tied closely to the electrical generation of the solar panels.”

MISSE is owned and operated by Aegis Aerospace Inc., which has recently added a new component that will allow measurement of the current-voltage relationship (I-V curve) for photovoltaic devices while they are operating on the exterior of the ISS. With this new capability, cameras, and other instrumentation, the facility will gather data about operation during dramatic temperature swings, frequent changes in illumination levels, space-borne radiation, impact of space debris, and exposure to the erosive effects of atomic oxygen.

The Georgia Tech devices are planned for launch later in 2025 as part of Aegis Aerospace’s MISSE-21 mission.

Juan-Pablo Correa-Baena, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Materials Science and Engineering, develops perovskite solar cells that have efficiencies of around 22 percent. These cells can be cheaper, thinner, easier to produce, more flexible — and more tolerant of radiation — than more traditional solar cell materials. But they tend to degrade over time.

“We’ve been doing a lot of work to prevent those degradation processes from happening, using things like encapsulants that are hydrophobic,” he said. “And there are hundreds of different chemistries that we’ve been working with to try to make these materials more resilient. For us, one of the goals of this mission is to learn how the different chemistries we produce will behave when they are in space.”

Perovskite materials can produce power with layers just a fifth or sixth as thick as conventional solar cell materials, and they more easily conform to surfaces, noted Carlo Andrea Riccardo Perini, Research Scientist in Correa-Baena’s lab. “With a much thinner layer, you can make the cells lighter,” he said.

For more information, contact