It’s a classic case of beginner’s luck. Thomas Berger had just started his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering at EPFL’s School of Engineering when he made his now-patented discovery, which has already been published. His thesis built on work he had started as a master’s student, but with the help of a 3D printer. This led to the promising technology that’s now attracting interest from investors.

Berger conducted his research at the laboratory headed by Mohamed Farhat, which studies complex fluid dynamics for applications including sailboats and hydropower turbines. “Turbines create particular challenges from both a scientific and engineering perspective,” said Farhat, who also supervised Berger’s thesis. “We’re aiming to address those challenges by running experiments on our large equipment. The biggest challenge relates to flow-induced vibration, which is a major problem for turbine designers as well as operators.” The key to Berger’s system is to eliminate the vortices that cause much of the vibration.

Vortices form when a fluid such as air or water flows over an obstacle. They’re created by such things as airplane wings, the ferries crisscrossing Lake Geneva, and the Burj Khalifa skyscraper in Dubai. Once the fluid starts to flow over the obstacle at a certain velocity, alternating vortices are created in the obstacle’s wake that exert oscillating pressure on its surface, resulting in vibration. These vortices can be very strong and damage turbines or even bridges, as occurred with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in the U.S. in 1940. They were first identified by engineer Theodore von Kármán in 1911 and are now known as Kármán vortices.

When Gustave Eiffel built his 330-meter-high tower in Paris in 1887, Kármán vortices hadn’t yet been discovered. “The tower’s porous structure is undoubtedly what saved it,” said Farhat. “That structure mitigated the formation of strong vortices. It was a real stroke of luck!” In fact, it was this porosity that gave Berger the idea for his research.

Engineers have already devised various solutions for attenuating Kármán vortices, such as by tapering the trailing edges of turbine blades where the vortices form. These solutions have proven to be effective to varying degrees but don’t entirely do away with the problem.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Farhat and Berger.

Tech Briefs: What was the catalyst for this work?

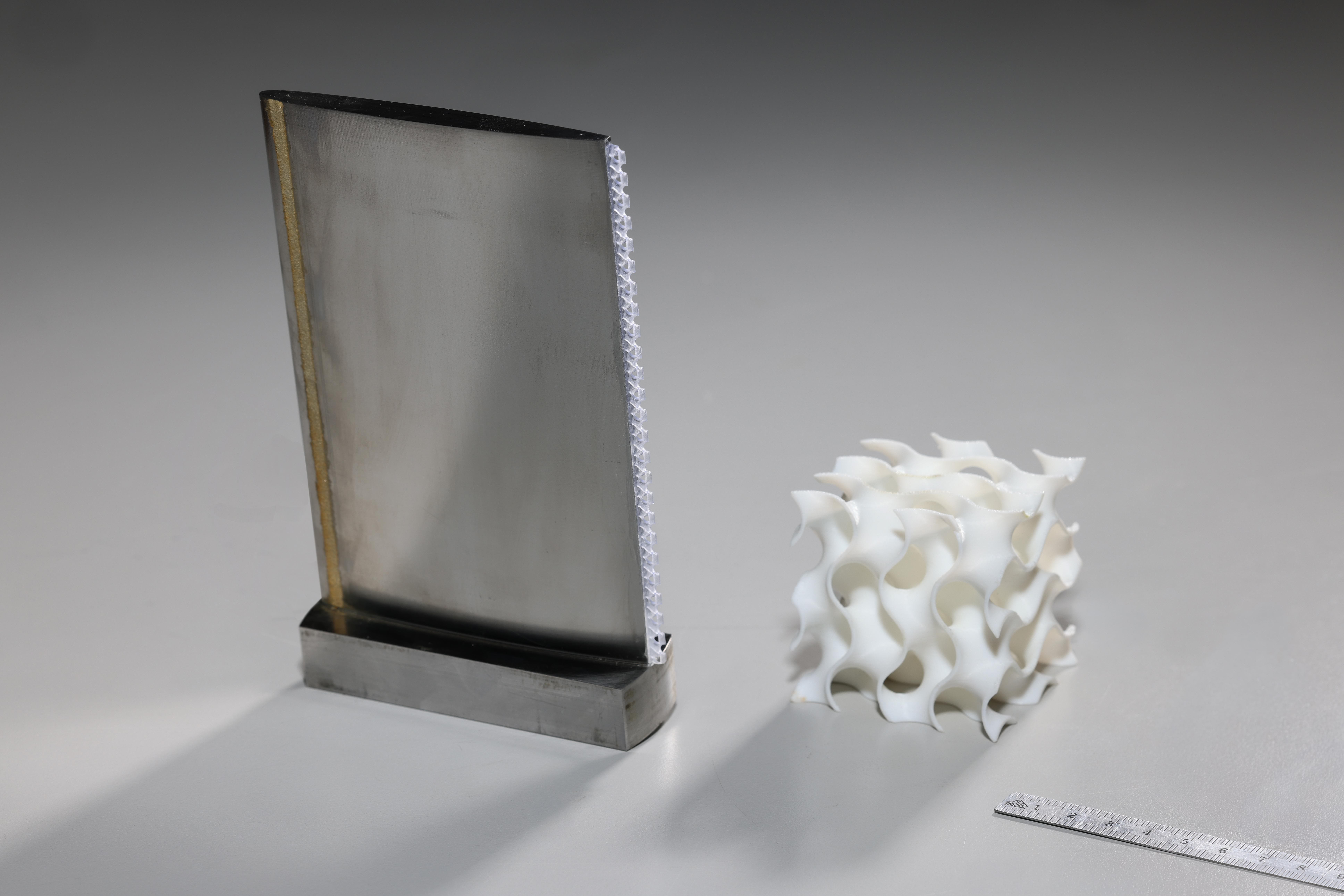

Farhat: The most important thing is, Thomas, about two years ago, was looking for something porous; porosity is something that has been pursued for a long time. He was quite good in 3D printing, so he gave it a try and started printing. We just needed to figure out what size to give the pores. In the beginning, we had to come up with some different porosity values. And the result was just wonderful.

I’ve been here for over 25 years doing research on this topic with many Ph.D. students; we have tried so many things with collaborations in and outside Switzerland. I said, ‘This is something that we need to patent,’ and that’s what we did. We just released the first paper, and we have another paper in the pipeline.

These kinds of surfaces, minimal surfaces, were invented by an American guy who passed away a year or so ago at the age of 92. He was a mathematics guy, who was just figuring out how to build a surface without any idea how to use this in real life. Applications came 20-30 years later, but nobody put this in a flow to control the vibration. We can think about the wing of an airplane, a blade of a turbine, many things; we’re trying to understand what’s going on. We have some idea about the physics behind this, which we’re still working on.

But we’re quite confident that it should give some interesting results. Going back to the wind turbine example, sometimes they make a lot of noise. If we can embed this kind of structure, maybe we can fix that.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how it reduces the vibrations?

Farhat: Why is this reducing the vibration? This is the question that we had in the beginning. Normally, what you try to do is avoid symmetry; you can implement some geometric changes to do so. This has the possibility to reduce the noise, maybe, by half but never fully get rid of it.

Berger: And how it works is: If you have a shape, you have two vortices: the upper vortex and the lower one. If you remove the symmetry, then the lower vortex and the upper vortex generate at different places. So, when they move, they end up in the same places, and they collide. They reduce the strength of the vortex by a lot.

Tech Briefs: Where do you go from here?

Farhat: The next step in this Ph.D. thesis is to bring this to real life. Now, the results are in the lab. This technology is beating every technology we may imagine to cancel or destroy these vibrations.

Berger: This is the biggest challenge. Now it works on a single foil, but if we want to go into a turbine the flow is a bit different. We have to make that work.

If it’s for a boat or airplane foil, it should be pretty straightforward. But for a turbine, there are many challenges to bring such geometrics to it.