Physicists have uncovered a link between magnetism and a mysterious phase of matter called the pseudogap, which appears in certain quantum materials just above the temperature at which they become superconducting. The findings could help researchers design new materials with sought-after properties such as high-temperature superconductivity, in which electric current flows without resistance.

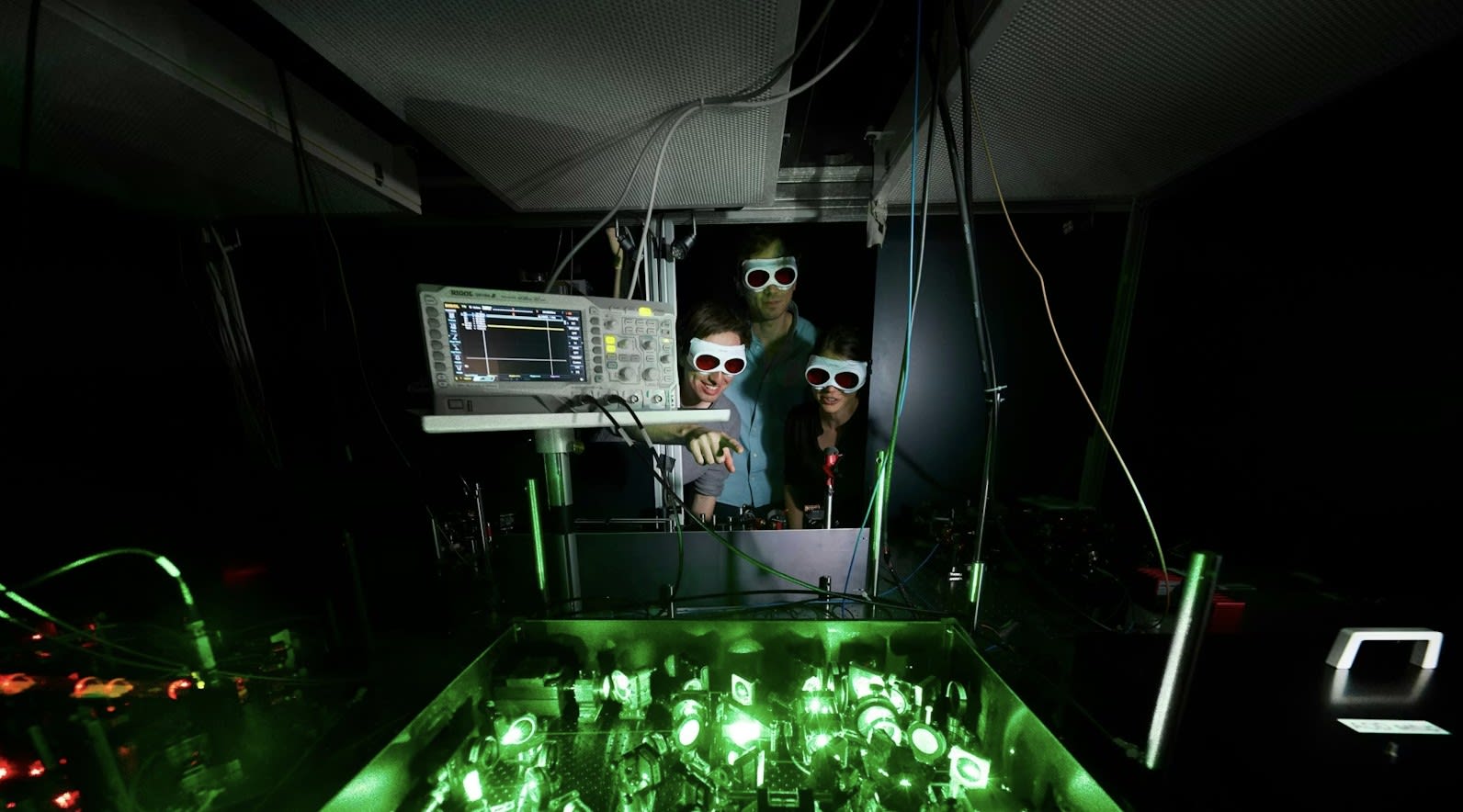

Using a quantum simulator chilled to just above absolute zero, the researchers discovered a universal pattern in how electrons — which can have spin up or down — influence their neighbors’ spins as the system is cooled. The findings represent a significant step toward understanding unconventional superconductivity and were the result of a collaboration between experimentalists at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Germany and theoretical physicists, including Antoine Georges, Director of the Center for Computational Quantum Physics (CCQ) at the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute in New York City.

Superconductivity has driven decades of research and holds the promise to revolutionize everything from long-distance power transmission to quantum computing. However, superconductivity is still not fully understood. In many high-temperature superconductors, the transition to the superconducting state does not emerge out of a conventional metallic state. Instead, the material first enters a curious intermediate regime known as the pseudogap, in which electrons start behaving in unusual ways, and fewer electronic states are available for electrons to flow through the material. Understanding the pseudogap is widely considered essential for unraveling the mechanisms behind superconductivity and designing materials with improved properties.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Georges and Lead Author Thomas Chalopin of the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced?

Georges: The real feat in the paper is about being able to do analog quantum simulation of a difficult quantum model computationally. So, primarily, really the challenge and the achievement are experimental challenges.

Chalopin: The nice thing is that we are able to do what is called analog quantum simulation of these models, which is not trivial at all. As for the technical challenges, I would say it's not like there was a breakthrough and suddenly we were able to do it. It was over years and years of working and improving the experiment up to a point where it was in a state where it was stable enough to acquire some statistics, because in the end it's a statistical analysis of what we see and really being able to be precise enough.

We use a quantum gas microscope. It enables us to see each of the atoms basically in a lattice, to see their spins as well in a sufficiently controlled and stable manner so as to acquire sufficient statistics to observe. One of the key challenges in the field is to get colder and to be sufficiently cold to observe what we observed. So it's been years of working, trying to get the best experiment possible, and then being able to make measurements. It’s not like from one day to the next there was a breakthrough.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms what the pseudogap is?

Georges: This all goes back to the discovery of the copper oxide high-temperature superconductors at the end of the 1980s. They discovered a family of copper oxides that have a record high — certainly at the time — critical temperature for superconductivity. The surprising thing about this family of materials is not only that they are superconducting at such a high temperature, but the fact that their non-superconducting metallic state is highly unconventional.

What happens in the pseudogap is that there are signatures in the metallic state that do not correspond to the standard behavior of a metal, and suggest that as you cool down the system, there is a deficit of low-energy situations. The system does not quite become an insulator, which would mean no low-energy situations at all. But it loses some of its low-energy situations. For example, to speak a little bit in technical terms, if you measure something like the magnetic susceptibility, which is the response of the material to a uniform magnetic field, in a standard metal it is constant as a function of temperature. While in the pseudogap regime, it collapses as you go down, hence indicating a deficit of excited states. The pseudogap is that deficit of excitation.

To understand that state, theorists like me have been setting up a number of computational methods — doing computations of the system is highly difficult. Simulating this, even on the most powerful computer in the world, is just plain impossible. One needs to find clever algorithms and compression methods, machine learning methods, etc. For many years, it's fair to say that computational methods running on classical computers had the lead on this. What has happened is that finally quantum simulation in its analog form is catching up.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research, work, etc.?

Chalopin: This state is still in a normal phase of these materials, which means that it's not yet superconducting. So I would say the big challenge is to lower the temperature more to see if there is anything else happening at lower temperatures. This is still an open question I would say, because there are some theories, but no one really knows what's going to happen and what is exactly the nature of this transition to the superconducting state. I would say a natural next step from the experimental point of view is to try to go colder.

Experimentally, we are using machines that can study systems with limited sizes and with some experimental issues, problems that need to be tackled at some point. This is quite technical, but we need to make sure that the system is sufficiently big and sufficiently homogeneous to really have a faithful simulation. There are some technical improvements that could be done on the experiment to improve the quality of the simulation. That's one experimental direction that one could go through.

And the last one that I would say, and is the most interesting to me, is to actually get experimental signatures on our quantum simulation machine that are closer to what material science people do.