Coaxial electric heaters have been conceived for use in highly sensitive instruments in which there are requirements for compact heaters but stray magnetic fields associated with heater electric currents would adversely affect operation. Such instruments include atomic clocks and magnetometers that utilize heated atomic-sample cells, wherein stray magnetic fields at picotesla levels could introduce systematic errors into instrument readings.

The resistance of the graphite film can be tailored via its thickness. Alternatively, the film can be made from an electrically conductive paint, other than a colloidal graphite emulsion, chosen to impart the desired resistance. Yet another alternative is to tailor the resistance of a graphite film by exploiting the fact that its resistance can be changed permanently within about 10 percent by heating it to a temperature above 300 °C. Figure 2 depicts a coaxial heater, with electrical leads attached, that has been bent into an almost full circle for edge heating of a circular window. (In the specific application, there is a requirement for a heated cell window, through which an optical beam enters the cell.)

This work was done by Dmitry Strekalov, Andrey Matsko, Anatoliy Savchenkov, and Lute Maleki of Caltech for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

NPO-43569

This Brief includes a Technical Support Package (TSP).

Coaxial Electric Heaters

(reference NPO-43569) is currently available for download from the TSP library.

Don't have an account?

Overview

The document discusses the development of coaxial electric heaters designed to eliminate stray magnetic fields, which is crucial for precision applications such as atomic clocks and magnetometers. These devices typically require heating, but traditional heating methods can create unwanted magnetic fields due to electrical currents, which can interfere with sensitive measurements, especially in small atomic cells.

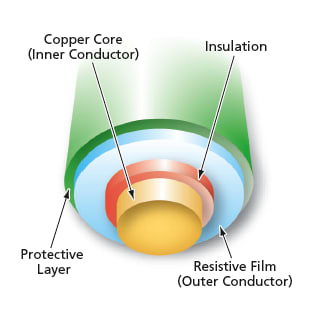

The coaxial heater presented in the document is a novel solution that is inherently free of magnetic fields, allowing it to be placed in close proximity to atomic cells without introducing interference. The heater is constructed by immersing a copper wire in a colloidal graphite emulsion. Upon drying, a thin, uniform film of high-resistance graphite forms around the wire, creating a coaxial conductor. The current flows through the copper core and returns via the graphite film, which can be adjusted for resistance by varying the film thickness or using different conductive materials.

One of the key advantages of the graphite layer is its ability to have its resistance permanently altered by exposure to high temperatures (above 300°C), allowing for fine-tuning after the initial construction. The entire structure is protected by a high-temperature epoxy layer, ensuring durability and functionality.

The document highlights the heater's small size, coaxial configuration, and mechanical flexibility as significant features. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for applications in space or airborne environments, where size and power constraints are critical. The coaxial design is emphasized as the most important aspect, as it mitigates the risk of stray magnetic fields that can lead to systematic errors in measurements.

The document concludes by noting that, to the best of the authors' knowledge, there are no commercial analogues of this coaxial heater available, underscoring its uniqueness and potential impact on the field of precision measurement technologies. Overall, the coaxial electric heater represents a significant advancement in the design of heating elements for sensitive scientific applications, addressing both performance and operational challenges.