Tech Briefs: What got you started on the project?

Isabel Arias Ponce: Within the field of additive manufacturing, one of the main hurdles, especially with light-based techniques, is that it's very difficult to fabricate features that are not well-supported but are overhanging or free floating. To fabricate those structures, people typically add what’s called support material, which is usually made of the same material as the final. Since it's all the same chemistry, after fabrication, the support material must be manually removed, usually with mechanical force. That can not only end up damaging the final parts, but it also adds a lot of time-consuming manual steps.

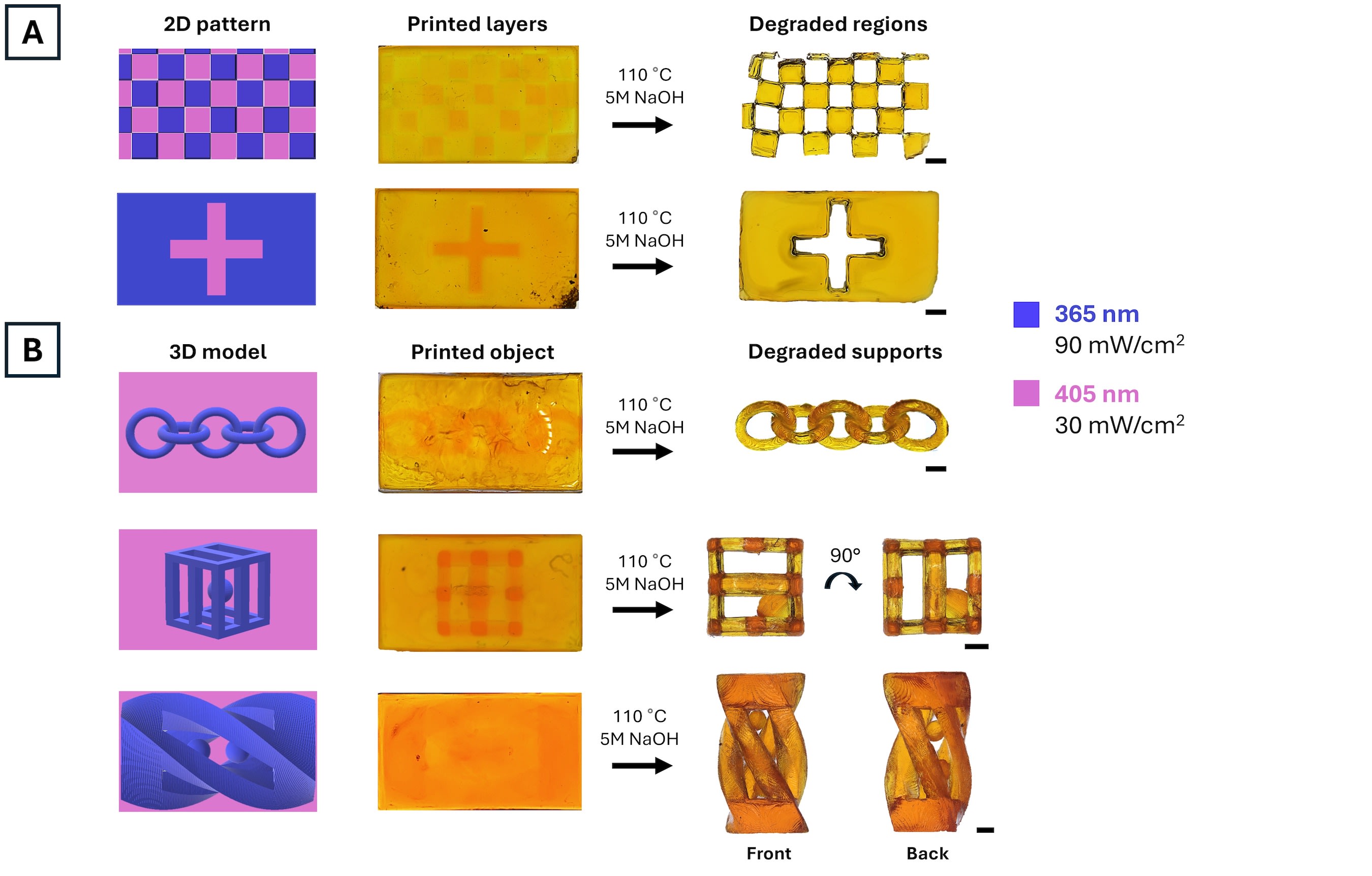

So, for my project I wanted to find a more streamlined way to fabricate the free-floating structures without the manual labor associated with removing the supports. To do that, we had the idea of using a single-pot resin that would allow us to selectively pattern the permanent regions and the support material, depending on the wavelength of light that was irradiated onto it. Then instead of having the supports manually removed with mechanical tools, we could simply dip the final structure into an aqueous solution to degrade away the support material and reveal the final structure. In that way, we would get high-resolution features without residue and without damaging the parts.

Tech Briefs: Could you talk about the interaction between the wavelengths and the material?

Ponce: Our one-pot resin is different from other resin materials in that it can trigger two different reactions based on the wavelength with which it’s irradiated. When we irradiate UV light onto the resin, it will predominantly trigger an epoxy-based network that's our final structure. And then when we irradiate with visible light, which is at a different wavelength, a different network will form — a degradable material. So, based on the pattern of light at these two wavelengths, we can have regions that are epoxy and will remain or methacrylate-based regions that are degradable.

Tech Briefs: Does the light have to have a certain energy to cause the reaction?

Ponce: Yes, part of the development of the resin formulation was not only to understand what chemistries would work, but also the light intensity and the duration of the exposure that would form the networks. If you irradiate too little, everything might degrade away. And if you irradiate for too long, everything might be permanent and not degradable, so you wouldn’t get the contrast. So, part of the work was to figure out the power and the duration as well.

Tech Briefs: It must have taken you a long time to perfect this process.

Ponce: Yes, the troubleshooting was time consuming, but in our paper, we walked people step-by-step as to how we developed our system. Hopefully that will enable other researchers to use it or develop similar materials in less time.

Tech Briefs: Was dual wavelength an existing process or is that something brand new?

Ponce: What's different about our project is the patterning of the permanent and the degradable regions for these specific applications, but there has been a lot of previous work on wavelength systems.

Tech Briefs: It must have been very difficult to build the printer.

Ponce: Yes, that was all developed in-house by optics engineer Bryan Moran. He developed a dual-wavelength negative imaging system (DWNI), different from other dual-wavelength printers. It uses only a single digital micromirror device (DMD), which receives both wavelengths of light. The DMD projects the different patterns of wavelengths depending on the position of the mirror.

Typically, DMD is used for a lot of the digital light processing (DLP) printing systems. It uses two different mirror positions for either letting the light go through or rejecting the light. But the way Moran set it up, is that in the off position, where light should have been rejected, he had the second beam coming in. So, then you have a sort of inverse irradiation pattern of both wavelengths, with both of them projected simultaneously.

Tech Briefs: Do you create the patterns by moving the mirrors?

Ponce: Yes, we feed digital light projection patterns to the DMD, which positions the mirror to project either wavelength. So, there's no need to use two independent DMDs or sequentially project wavelengths, it's all done simultaneously.

Tech Briefs: What are the light sources?

Ponce: We use high-power LEDs at 365 and 405 nanometers, but you can get any wavelength you want; it's very modular in that way. And then, different wavelengths will work with different initiators and reactions, so there's room to explore other materials.

Tech Briefs: What do you mean by different initiators and reactions?

Ponce: The initiator is the molecule that absorbs the light and will generate the species that starts the reaction. So, if we change the initiator, we can trigger different reactions and explore other materials.

Tech Briefs: If everything is mixed together, wouldn’t you have some amount of the dissolvable material incorporated into the final part?

Ponce: Yes.

Tech Briefs: Wouldn't that weaken the structure?

Ponce: It does — you're compromising the density of your final part by having both of the materials in one pot. But to maximize the loading of the final parts, we chose a degradable material that requires a very small amount to solidify. There are different materials we could have chosen that might gel more quickly or degrade faster, but then we would need a higher concentration of the material to get it to solidify. Therefore, we chose a thermoset that allowed us to get that region to a solid with only a small amount of material, which would maximize the amount of the final material that we're really interested in.

Tech Briefs: What sorts of applications might your system be used for?

Ponce: Our system would be most useful in the fabrication of geometries that require intricate, unsupported internal features, and at high fidelity. Some of those applications would be microfluidics that have overhanging cavities, cantilevers, or actuators, and also specialized lattices.

Also, if you think about a joint structure that requires two mobile components that can rotate — that kind of geometry could be printed at once. You would just need to have a space in between the structures and instead of having to assemble them after fabrication, you could have both components printed in place and then degrade away the mobile interface after the post-processing step. That could help us streamline and automate the manufacturing of some non-assembly parts.

Tech Briefs: What are the next steps in your work?

Ponce: I am thinking of a couple of different directions to improve the process. I've been exploring ways to optimize the reactivity of the epoxy material with photosensitizer molecules that could increase light absorption at the right wavelength. And I am exploring how I can use strategies to improve upon the mechanical properties of the final parts by integrating more of the final material and making the reaction more efficient.

I'm also interested in seeing how this one-pot resin could be used with other printing platforms, especially the ones that have been developed here at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), or are in development here, like volumetric additive manufacturing and two-photon lithography.

Our paper was published in ACS Central Science .