Vat photopolymerization is a 3D printing technique in which a light-sensitive resin is poured into a vat, and then selectively hardened into a desired shape using a laser or UV light. But this process is mostly used only with light-sensitive polymers, which limits its range of useful applications.

While some 3D printing methods have been developed to convert these printed polymers into tougher metals and ceramics, Daryl Yee, head of the Laboratory for the Chemistry of Materials and Manufacturing in EPFL’s School of Engineering, explains that materials produced with these techniques suffer from serious structural setbacks. “These materials tend to be porous, which significantly reduces their strength, and the parts suffer from excessive shrinkage, which causes warping,” he said.

Now, Yee and his team have published a paper in Advanced Materials that describes a unique solution to this problem. Rather than using light to harden a resin that is pre-infused with metal precursors, as previous methods have done, the EPFL team first creates a 3D scaffold out of a simple water-based gel called a hydrogel. Then, they infuse this ‘blank’ hydrogel with metal salts, before chemically converting them into metal-containing nanoparticles that permeate the structure. This process can then be repeated to yield composites with very high metal concentrations.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Yee and his team.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing this new 3D printing technique?

Yee and Team: The biggest technical challenge we faced was increasing the metal content in the hydrogel. For context, we previously pioneered a hydrogel-to-metal printing technique (Saccone et al. Nature 2022) that used heat to convert a 3D-printed metal-ion-containing hydrogel into metal. In brief, the heat simultaneously removes the polymer while sintering the metal together to form the desired metal part. However, due to the low metal content in the hydrogels (~10 wt%), the metal parts produced experienced large shrinkages (>60 percent) and low densities (~50 percent). Thus, while a great advance in the field at that time, the parts made were not robust enough for practical use. Since our 2022 work, multiple groups around the world have tried to increase the metal content in the hydrogel to reduce shrinkage and increase part density, with the state of the art going up to 30 wt% of metal. (Spoiler: We got up to 80 wt% of metal in our work!)

We knew that the key to achieving ceramic and metal parts with low shrinkages and high densities was to have hydrogels with high metal contents. However, hydrogels can only hold a limited amount of metal ions. We realized that to reach the metal contents needed, we had to think beyond metal ions. We thus came up with this idea of repeatedly converting the metal ions into metal-containing nanoparticles. In doing so, we could progressively increase the metal content of the hydrogel (now in the form of metal-containing nanoparticles), while still staying under the hydrogel metal-ion limit.

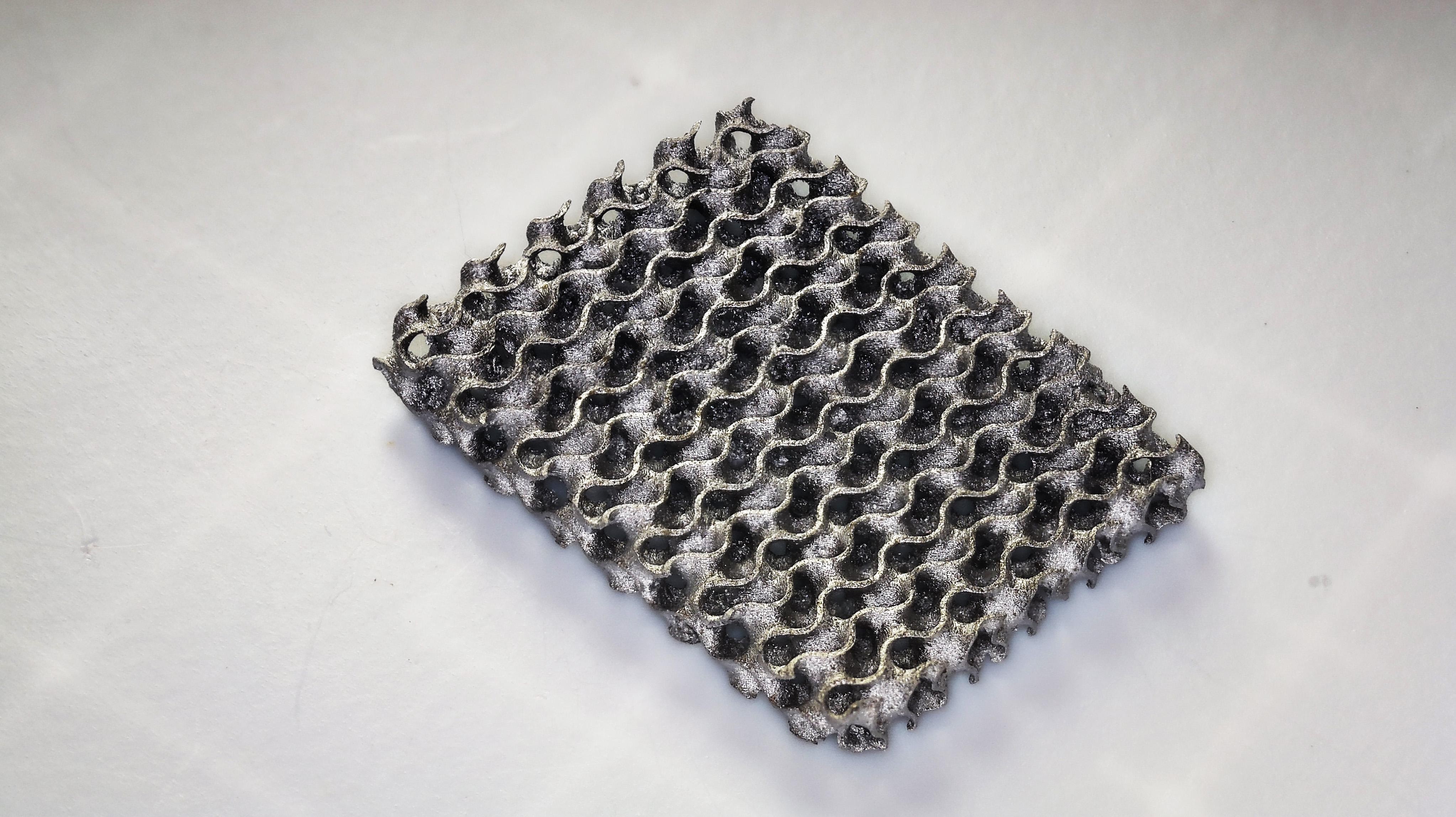

The challenge was how to do so. We needed to reliably convert the metal ions in the hydrogel into metal-containing nanoparticles that permeated throughout the structure, i.e. grow the nanoparticles homogenously within the hydrogel. This is challenging for a few reasons: 1) the growth conditions can be aggressive, which would damage or destroy the hydrogel, and 2) inhomogeneous growth could cause warping and/or cracking during the final thermal treatment step. To achieve this, Yiming Ji, the researcher who led this study, screened multiple reaction conditions (time, temperature, reagents, etc.) to determine the optimal processing conditions for each metal fabricated in the study. These “infusion-precipitation” processes (as we call them in the study) form the core of the 3D printing technique. As you can see in the study, he was able to successfully develop methods to grow a variety of metal oxide and metal nanoparticles within the hydrogels. Essentially, he was able to convert the hydrogels into high metal wt% hydrogel composites (as high as 80 wt%!). By carefully heating the hydrogel composites in the appropriate atmospheres, we were then able to obtain ceramics and metals with low shrinkages (as low as 20 percent) and high densities (~90 percent).

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how it works please?

Y&T: We start by using a light-based 3D printer to create a structure made of a soft, water-based material called a hydrogel. This “blank” hydrogel is then soaked in a solution of water-soluble metal salts to infuse it with metal salts. The metal-salt infused hydrogels are then immersed in a second solution of chemicals to convert the metal salts into metal-containing nanoparticles that permeate the structure. This step essentially causes the growth of metal-containing nanoparticles within the 3D printed hydrogel. By repeating this infusion–conversion process several times, we can build up a high concentration of metal-containing nanoparticles within the hydrogel. Finally, a controlled heating step removes the remaining hydrogel, leaving behind a dense, strong metal or ceramic structure that precisely matches the original 3D-printed shape. One important distinction of our method is that because the metal salts are only introduced into the hydrogel after printing, we can transform a single hydrogel into an almost infinite number of different materials — from composites to ceramics and metals.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any updates you can share?

Y&T: The automation work is still in its preliminary stages, but in brief, we worked with a very talented engineer, Shengyang Zhuang, who is now pursuing a Ph.D. at UCL in the U.K., to develop a robotic platform to automate our infusion-precipitation process. Shengyang was able to complete a working prototype system, and we are now working on improving it and integrating it into our future projects. Stay tuned!

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research/work/etc. beyond what you just described?

Y&T: Absolutely! Now that we are able to fabricate parts that are robust enough for practical applications, we are starting to explore what we can do with the parts that we can make. We have some ongoing collaborations with both academic and industrial partners to see how our 3D printed parts can be used for their purposes. Internally, we are working on improving the technology further. We’ve already reduced shrinkage from 80 percent to 20 percent with this new generation of printing technology. Can we bring this down to almost 0 percent? That would be an even bigger step forward for the technology.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

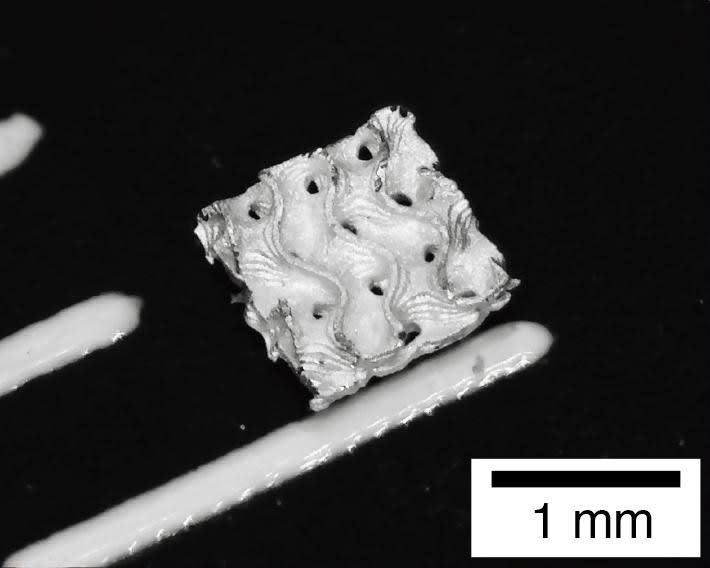

Y&T: Our metal-printing technology complements existing conventional metal printing AM technologies in the part sizes and materials that it can achieve. For example, creating metal structures with walls thinner than 0.3 millimeter is extremely challenging for most conventional metal 3D printing techniques like selective laser sintering (SLS), and only a few advanced systems can reach around 0.1 millimeter. The task becomes even harder when printing highly reflective metals such as copper and silver. Using our approach, we achieved silver structures with features as small as 0.03 millimeter — about one-third the width of a human hair.

It’s also important to carefully choose the chemistry used for nanoparticle growth within the hydrogel scaffold. The process requires delicate handling, as hydrogels are inherently soft and can become fragile after several infusion-conversion cycles. These are essential for achieving consistent and high-quality results.