Unlike lithium-ion technology, which currently dominates the energy storage market and relies on expensive, environmentally damaging materials, sodium is far more abundant and widely available. However, developing sodium-ion batteries that can compete on performance has remained a challenge.

In a study published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A, researchers detail how an existing sodium-based material, sodium vanadium oxide, can perform significantly better when the water it naturally contains is not removed.

The material — known as a nanostructured sodium vanadate hydrate (NVOH) — showed a major boost in performance, storing far more charge, charging much faster, and remaining stable for more than 400 charge cycles.

In tests, the ‘wet’ version of the material could hold almost twice as much charge as typical sodium-ion materials, placing it among the best-performing cathodes reported to date.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Dr. Daniel Commandeur, Surrey Future Fellow.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while achieving this battery breakthrough?

Commandeur: The challenges were largely associated with understanding what was happening with the crystal structure. We were really scratching our heads about it, but basically there are vanadium oxides, which have been around for a long time; people are just now, in the last few years, getting switched on to actually applying them to sodium ion batteries. But actually understanding what was going on inside the material itself was the biggest challenge.

Tech Briefs: You're quoted in the article I read as saying, “Sodium vanadium oxide has been around for years, and people usually heat treat it to remove the water because it's thought to cause problems. We decided to challenge that assumption.” My question is: What made you decide to challenge the assumption?

Commandeur: My whole research specialization is trying to make aqueous batteries. So, I'm trying to make batteries that have water-based electrolytes; they've received a lot more attention recently. You know, the first batteries were made with water-based electrolytes, but we are trying to make rechargeable, high-power, high-energy-density ones. So, it's kind of the new generation of these chemistries.

I always thought to myself sustainability is the bottom line. And the heat treatment step with a lot of these materials can actually be quite costly and a large source of the emissions through synthesis. If you're making normal Li-ion battery positive electrodes, you'll use an NMC or an LFP, both of which you have to heat greatly to form the right crystal structure. Whereas, these always have this really nice advantage that, right out of the box, you heat them up to about 200 degrees. But typical cathode heat treatment conditions are about 1,000 degrees. Typically, people would heat them up to 400 or 500 degrees.

I thought to myself, ‘Well, we're going to be putting these materials in water down the line anyway, and they're going to have to stand up to this exposure. So, why take the extra step to drive off the water? Why not just see what happens without introducing it?’

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans or further research, work, etc.? And if not, what are your next steps?

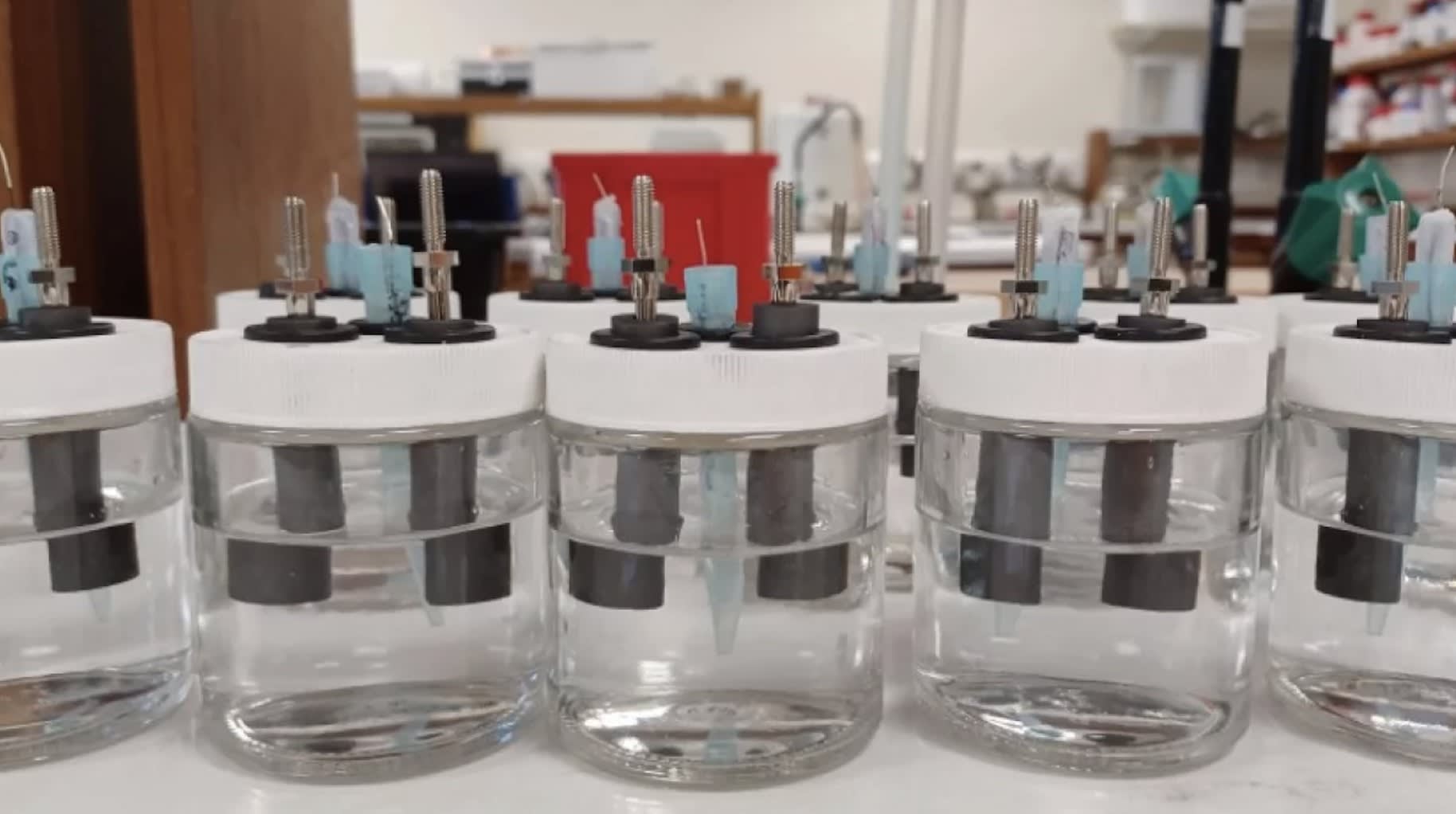

Commandeur: This is actually a really small part of a large research program. I'm still a bit of a one-man band at the University of Surrey; I got my independence a couple of years ago. I’m just looking to basically secure further funding to build a team —I’ve been working with students. We've looked at all sorts of different materials for sodium-ion batteries, and we are trying to zoom in on the ones that work well in a typical sodium cell and don't fall apart when you put them in water.

We've been casting our net quite broadly, looking at materials — manganese is a really interesting one that makes up a lot of battery research because whenever we look at the sodium-ion system we've always got sustainability and supply chains in mind. One of the big reasons we want to move from lithium to sodium is that we can extract it from seawater. We want less reliance on critical materials.

Another one is sodium ionic superconducting materials, which are not superconductors, they're super ionic conductors. They have these amazing cage-like structures that allow sodium to move in and out, and they're amazingly stable. We’ve had a lot of success lately applying these water systems, taking the step to apply them to a sodium chloride system, and actually seeing that they're not falling apart so quickly and they've got some really nice electrochemical propertiesas well.

Then there’s the desalination side of things. The work kind of touched on that, but there's a lot of engineering that needs to happen before we can make a battery that can extract salt from water and provide drinkable water.