Electric Vertical Take-off and Land (eVTOL) aircraft are set to become common in our skies, with one source estimating a staggering 52 percent CAGR for the market between 2023 and 2030. 1 The first fully FAA type-certified aircraft is on its way, with Joby Aviation, for example, passing three of the five stages required as of February 2024. 2 This is for an air taxi with a pilot and four passengers, with six rotors that can be tilted for vertical or horizontal flight at up to 200 mph.

Flying car concepts have been around for decades, but now, the move to sustainable aviation is ‘propelling’ the market forward. Even costs are claimed as an advantage, with projected passenger fares of just a few dollars per mile, 3 making a fast, quiet, and affordable airtaxi trip attractive to consumers.

Safety is the Over-Riding Concern

What is not attractive is the possibility of systems failure in an eVTOL craft — although some designs can glide, others can’t, and any craft is particularly vulnerable during the vertical phase of flight. Additionally, potential passengers will be wary of the industry goal of autonomous operation — eVTOL designers know that in theory this can be more reliable than a human pilot but only if the electronic systems are proven to be robust, even after multiple failures.

This all means that redundancy and monitoring must be at the heart of all of the systems, from batteries to rotors, the power conversion and distribution network, to flight control and navigation electronics. At the same time, the craft systems must be as small, lightweight and efficient as possible to get maximum range from the battery energy available and this is achieved by yet more electronics, electrical actuators and motors in a fly-by-wire arrangement, replacing heavy mechanical components and linkages in traditional designs.

Reliability of these redundant components and systems is key and a requirement has been set by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) of better than one billion hours mean time between failures (MTBF) for eVTOL craft. In real terms, this means a failure rate of less than 10-9 per flying hour. This equates, for example, to no catastrophic failures in eleven continuous flying-years for each craft in a fleet of 10,000 with a defined confidence level.

This is not practically achievable with a single system, so back up through equipment redundancy is required in case of failure. Particularly when the electronics is used for flight control, partial failure must also be allowed for — if a command to a throttle or surface is inaccurate because of a component degrading, this can be as dangerous as total failure, so a common practice is to have on-line redundancy, where system outputs are cross-checked or ‘voted’ against each other at various stages. For the highest reliability, at least three redundant systems might be used because with only two, if a discrepancy is registered, it can’t necessarily be known which system is the inaccurate one to be ignored. For example, the original space shuttle had four identical, redundant online flight control systems with a fifth as a further back up.

Power Distribution Must Also be Redundant

Redundant arrangements must not have any component or connection failure mode that could affect all systems together and an obvious cause of concern is the power supply and distribution network. A paper by NASA calculates that for a theoretical six-passenger quadrotor craft, a minimum of three batteries would be needed to meet the 10-9 per hour failure rate, any two of which should be sufficient for safe flight. Four separate drives and motors for each rotor would also be necessary, with the ability to operate safely with any two failed.

It can be expected that power distributed in an eVTOL craft will all be at DC, with main batteries at relatively high voltage, with high-power DC-DC converters generating lower voltage buses at perhaps 24 or 28V, or a voltage for specific equipment such as lights. Further board level DC-DCs would provide end voltages for the electronics. In the power distribution and DC-DC conversion architecture there are choices in the arrangement; redundant systems could be completely isolated to ensure no common failure mode, but this has the disadvantage that a single power rail failure takes down a complete system, forcing an immediate, precautionary, emergency touchdown in case a second failure occurs in any part of the remaining system.

Alternatively, power can be ‘diode-gated’ at different points so that if one path fails, the other(s) share the load and downstream electronics continues as normal. A pilot might then decide to continue, knowing which part has failed and how critical it is. This arrangement does, however, rely heavily on monitoring to signal that the component has failed and importantly, the monitoring circuitry itself has to be carefully designed so it cannot form a single point of failure. It must also be regularly exercised to check its correct functionality.

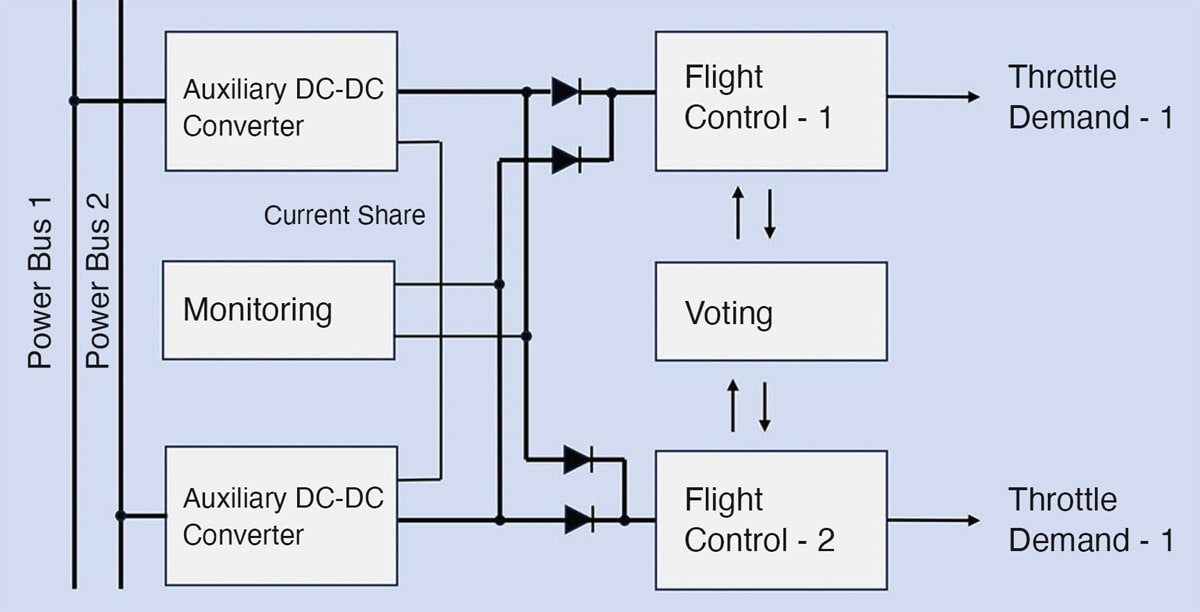

The gating approach also means that each power rail and any DC-DC conversion must be capable of supplying its share of the current plus that of any failed unit, so each needs to be over-sized for its normal running load. This is a cost, size, and weight overhead that might not be acceptable. An upside though is that under normal conditions, if sharing current, each DC-DC will be more lightly loaded, contributing to longer life and higher reliability for the converter. Figure 1 shows a system where DC-DC converters are supplied with gated power rails with monitoring and signaling for current sharing.

In this case, monitoring has to have the intelligence to detect if each DC-DC output is valid and if a gating diode fails short, which might not be otherwise noticed. If this happens, a DC-DC that fails with a shorted output to ground would drag down the supply to both flight control systems in the example of figure 1. In the figure, if the input of the ‘flight control’ block goes short, this would also take down both DC-DC outputs so a fuse or circuit breaker would be necessary in each power line.

The Operating Environment

As a new application, there are no historical standards for the operating environment for electronics in eVTOL craft, such as there are for automotive or traditional avionics. However, this does mean that there are not necessarily legacy requirements to meet, for example, existing avionics standards allow for high energy transients on supply rails from ‘load dumps’ but in the eVTOL application, these can be ‘designed’ to be absent. Some degree of filtering and transient protection would be present, however. Power rail quality standards might be based on the most severe military requirements, MIL-STD-704F and MIL-STD-1275 for example, with agreed exclusions, and MIL-STD-461 for EMC.

The physical environment is likely to be relatively harsh, with shock, vibration, and bump effects present and operating temperature range and thermal shock could be severe. DO-160 might be used, “Environmental Conditions and Test Procedures for Airborne Equipment” published by the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics.

Cooling for power converters is likely to rely on conduction through baseplates to the frame of the craft, as fans would be too unreliable and convection cooling levels would be difficult to guarantee, and would require larger DC-DC case sizes. In any case, the DC-DCs need to be highly efficient for the smallest possible size, highest reliability from minimum internal temperature rise and minimum energy wastage. With variation in operating altitude, humidity and air quality, encapsulated parts would naturally be preferred.

An Example Solution for Board-Mount DC-DC Conversion

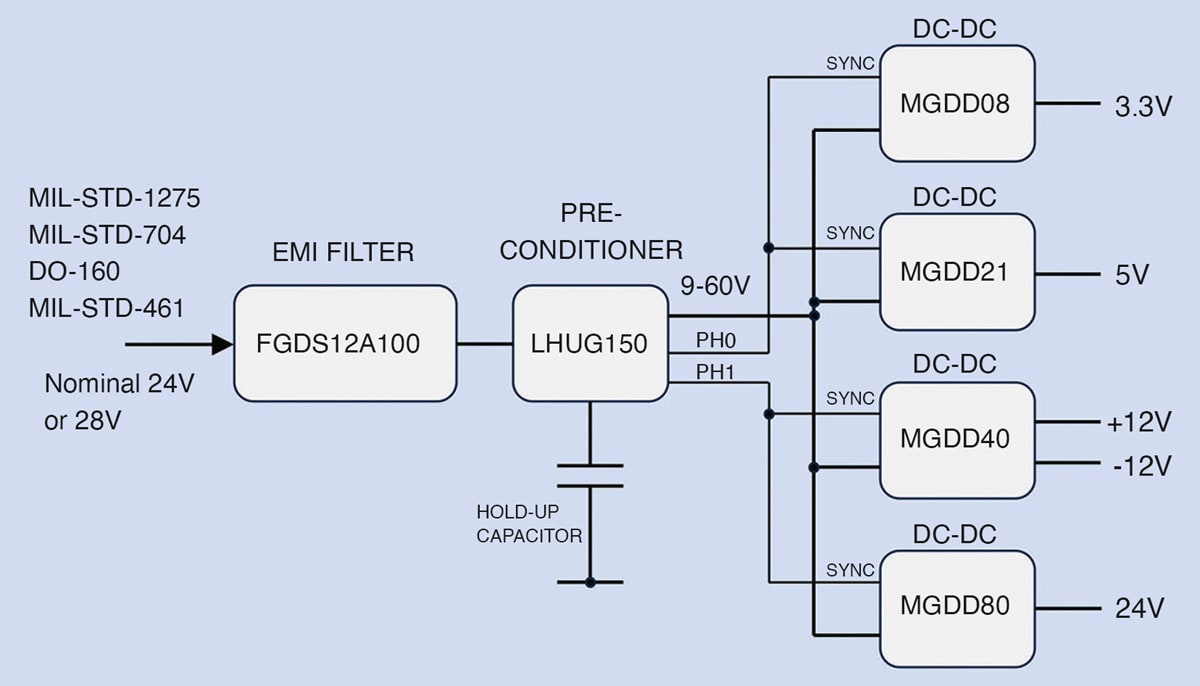

While the main high-power DC-DCs dropping battery voltage to perhaps a 24V or 28V bus might be custom designs, the downstream board-mount DC-DCs can be selected from off-the-shelf parts. Figure 2 shows an arrangement using parts from Gaia Converter who have long experience supplying power conversion products to the hi-rel market.

An EMC filter, part FGDS12A100, enables compliance with military standard MIL-STD-461 while the pre-conditioner module LHUG150 attenuates spikes and surges according to MIL-STD-1275, while providing active hold-up with supply dips from an external capacitor. This is kept ‘boosted’ up to a high voltage, whatever the input. The module handles loads up to 150W total at nominal voltages between 9-60VDC and incorporates reverse polarity protection, inrush control and soft start. Synchronization signals in two anti-phases are also generated for the downstream converters.

The end-load DC-DC converters shown are from Gaia’s compact MGD range, which are available with ratings from 4 to 500W. The encapsulated parts are suitable for cold-plate cooling and feature remote sense, voltage trim, an ON-OFF function and secure protection features which include output over-voltage and over-current, over-temperature and input under-voltage. Isolation is 1500VDC.

Conclusion

eVTOL power system architectures are not yet well defined, and with the wide variety of possible configurations, from small, unmanned drones through multiseat passenger craft, there may never be one standard. However, use of modular, scalable DC-DCs from a supplier such as Gaia Converter, with their track record and certifications in the hi-rel market, results in an economical, safe, and secure solution.

This article was written by Christian Jonglas, Customer Support Manager, Gaia Converter (Haillan, France). For more information, visit here .

References

- eVTOL Aircraft Market by Lift Technology, Propulsion Type, System, Mode of Operation, Application, MTOW, Range and Region – Global Forecast to 2030. Markets and Markets. 2022.

- Joby Completes Third Stage of FAA Certification Process. February 2024.

- Counting the Cost of Urban Air Mobility Flights. AIN Media Group. November 2021.