Human skin can feel a wide variety of sensations, such as a gentle squeeze, quick taps, or the thud-thud of a heartbeat. In contrast, phones, game controllers, and watches often output only vibrations to get the user’s attention. Unfortunately, this sudden fast shaking feels different from most everyday touch interactions, and it can quickly become annoying. Researchers at Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) in Stuttgart have developed cutaneous electrohydraulic (CUTE) wearable devices to greatly expand the haptic sensations that can be created by future consumer products.

CUTE wearable devices are electrically driven and can produce a remarkable range of tactile sensations, including pressing on the skin, slow and calming touch, and vibrations at a wide variety of frequencies, from low to high. This new approach to wearable haptic feedback thus offers unprecedented control over the tactile sensations that can be presented to users.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with First Author Natalia Sanchez, Ph.D. student at the MPI-IS.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing these wearable devices?

Sanchez: One of the biggest technical challenges was to develop a haptic actuator that has a compact size but that can also press on the skin with sufficient forces and displacements to be easily felt on a location of the body with low sensitivity, such as the back of the wrist. Typical wearable haptic devices use strong buzzing vibrations that can easily call our attention, even when worn on the wrist or inside a pocket. But, it’s difficult to create devices that provide slow moving touch and taps on the skin in addition to vibration, because our skin is less sensitive to slow moving touch, and thus, such devices need to have higher forces and displacements to provide strong sensations. To achieve high performance in these devices, we ran many experiments and design iterations focused on optimizing the design, size, and construction of the devices and we tested different material formulations to find the materials design that worked best for such haptic devices.

Tech Briefs: What was the catalyst for this project?

Sanchez: When we started the project, we identified a gap in the capabilities of many haptic devices. Typical haptic devices either focused on providing high-frequency vibrations, like the vibrotactile actuators in cell phones, or relied on pressure and slow motions, such as pneumatic wearable systems, which could not deliver fast vibrations. Further, most devices cannot recreate the sensations of making and breaking contact with the skin. We believed that an emerging technology known as HASEL (Hydraulically Amplified Self-Healing) actuators, could serve as the foundation for a versatile solution to bridge this gap in haptic actuation capabilities. These actuators had demonstrated promise as artificial muscles for robotics applications by providing both strong, sustained pressure, and fast actuation for diverse robotic systems. We then initiated a project to develop this technology for versatile wearable haptic devices that can generate different expressive haptic cues, from constant pressure and slowly changing touch, to fast vibration, and diverse combinations of such tactile sensations. To achieve this goal, we focused on creating high-performing downscaled actuators and suitable wearable devices for effective haptics. We developed insulation and safety systems for the safe operation of such high-voltage devices near the body and innovated with new materials designs suitable for the high actuation frequencies required for haptics.

Tech Briefs: Can you explain in simple terms how it works?

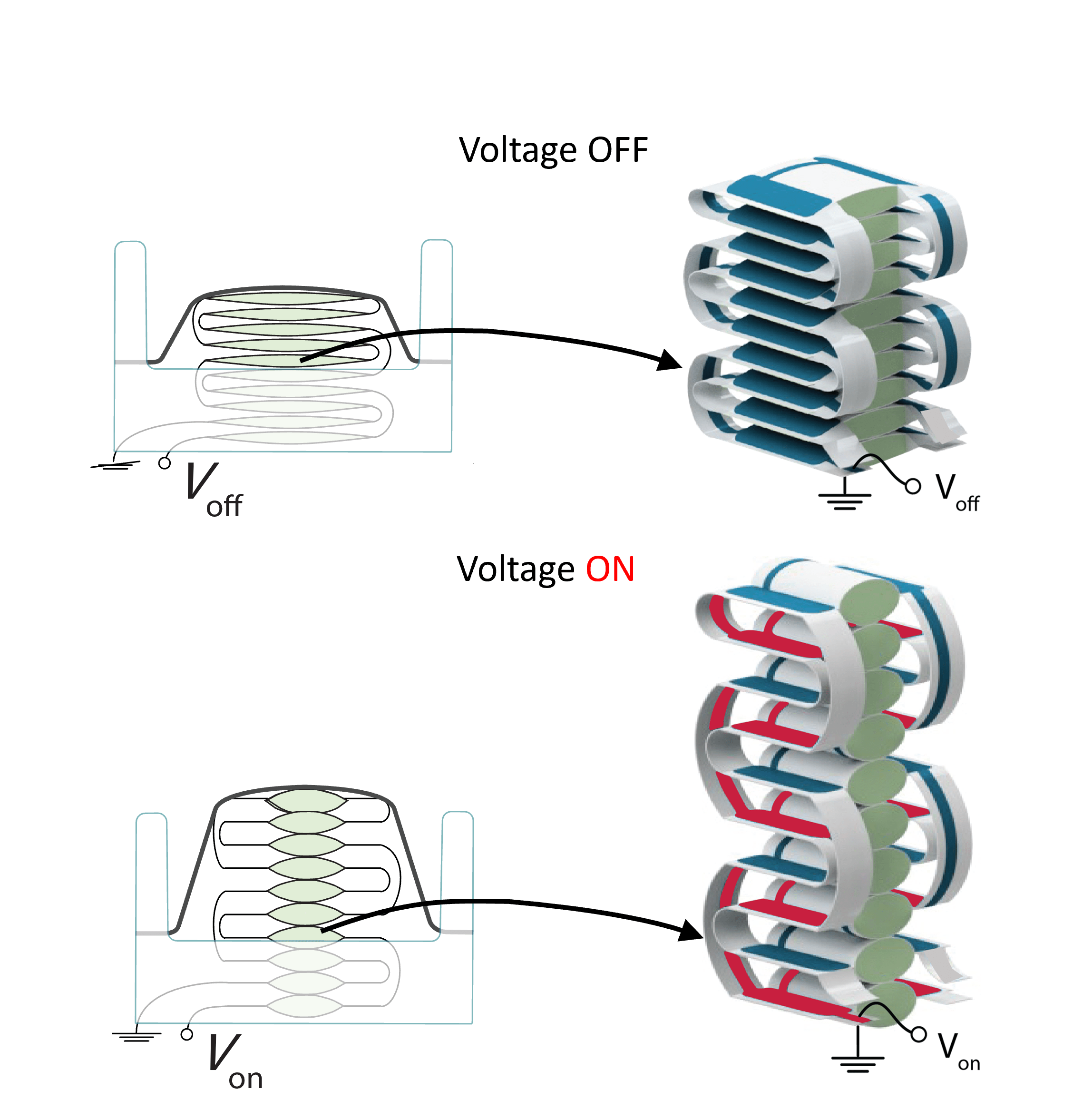

Sanchez: The CUTE devices are powered by a stack of 10 soft actuator pouches. Each actuator pouch is made of a flexible plastic film filled with fluid — imagine something like a Ziploc bag filled with oil. The outer sides of the pouches are partially covered by flexible electrodes at the top and bottom. When a voltage is applied, the electrodes squeeze the liquid out of the areas they cover, causing the pouches to change shape and expand in the middle, thus generating upward forces. By placing them near the skin and adjusting the voltage, we can control in real time how much and how quickly they press into the skin, allowing us to create a wide variety of tactile sensations. I include below a figure that shows how the stack expands in the device.

Tech Briefs: Do you have plans for further research/work/etc.?

Sanchez: Yes, in our group we are actively exploring the capabilities of this technology to create realistic and engaging feedback. Last year, we presented a demonstration at the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST), where we employed CUTE devices to enhance user experience by adding rich and expressive tactile feedback to virtual interactions. The demo was well-received by the public, and we plan to use this approach to study the effects of realistic haptic feedback in virtual interfaces.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any updates you can share?

Sanchez: Regarding future plans, we are also planning to investigate more complex tactile sensations in cutaneous electrohydraulic wearable systems to deepen our understanding of human tactile perception in response to various forms of haptic feedback. We hope that later this year we can release new results of our continuous work in this technology.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Sanchez: We conducted a user study that showed the haptic cues were easy to distinguish and we found that participants found almost all of them pleasant. The only exception was a buzzing vibration similar to those used in current commercial devices. This highlights the need for more widespread use of haptic devices that can create a variety of tactile sensations beyond vibrations that can communicate with the skin in more pleasant ways. After experiencing diverse haptic cues, many participants mentioned they had never felt anything like it, as they typically had only used vibrotactile devices. We believe the capabilities of these new tactile sensations pave the way for exploring experiences and use cases that have been largely unexplored so far. We hope that others take inspiration in our work, and build upon it, for example further developing user experiences that explore making and breaking contact with the skin and other tactile sensations in multiple body locations.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.