The next step for fully integrated textile-based electronics to make their way from the lab to the wardrobe is figuring out how to power the garment gizmos without unfashionably toting around a solid battery. Researchers from Drexel University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Accenture Labs in California have taken a new approach to the challenge by building a full textile energy grid that can be wirelessly charged. In their recent study, the team reported that it can power textile devices, including a warming element and environmental sensors that transmit data in real-time.

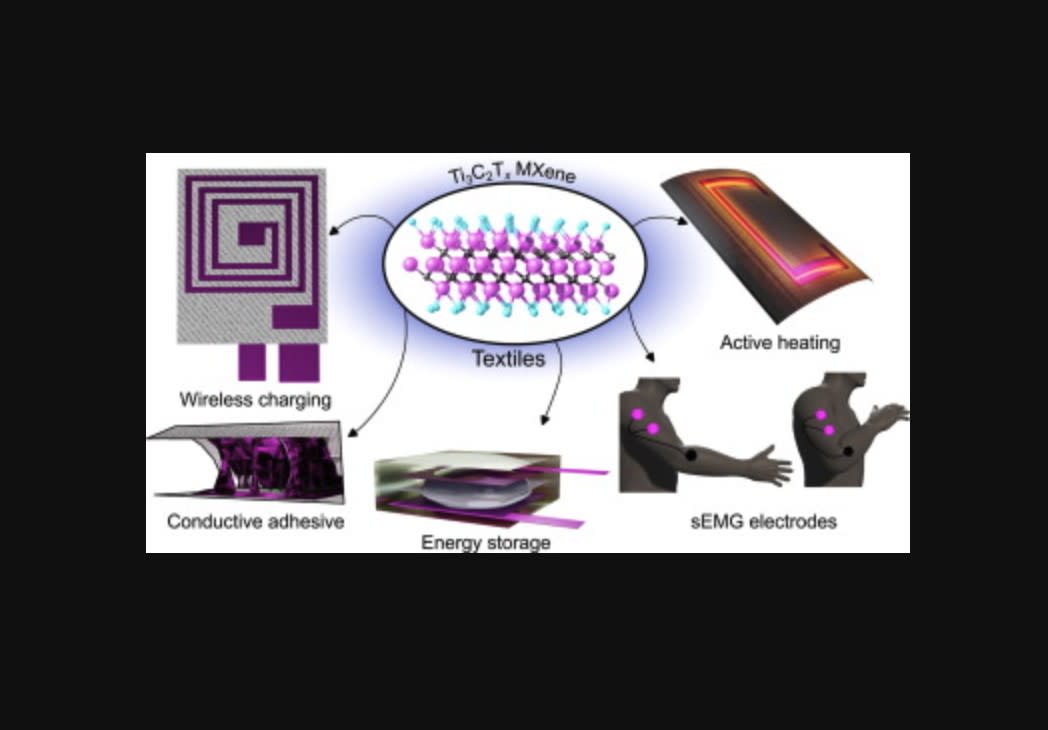

Published in the journal Materials Today, the paper describes the process and viability of building the grid by printing on nonwoven cotton textiles with an ink composed of MXene, a type of nanomaterial created at Drexel, that is at that same time highly conductive and durable enough to withstand the folding, stretching and washing that clothing endures.

The proof-of-concept represents an important development for wearable technology, which at present requires complicated wiring and is limited by the use of rigid, bulky batteries that are not fully integrated into garments.

“These bulky energy supplies typically require rigid components that are not ideal for two main reasons,” said Yury Gogotsi, Ph.D., distinguished university and Bach professor in Drexel’s College of Engineering, who was a leader of the research. “First, they are uncomfortable and intrusive for the wearer and tend to fail at the interface between the hard electronics and the soft textile over time — an issue that is especially difficult to tackle for e-textiles is the issue of washability.”

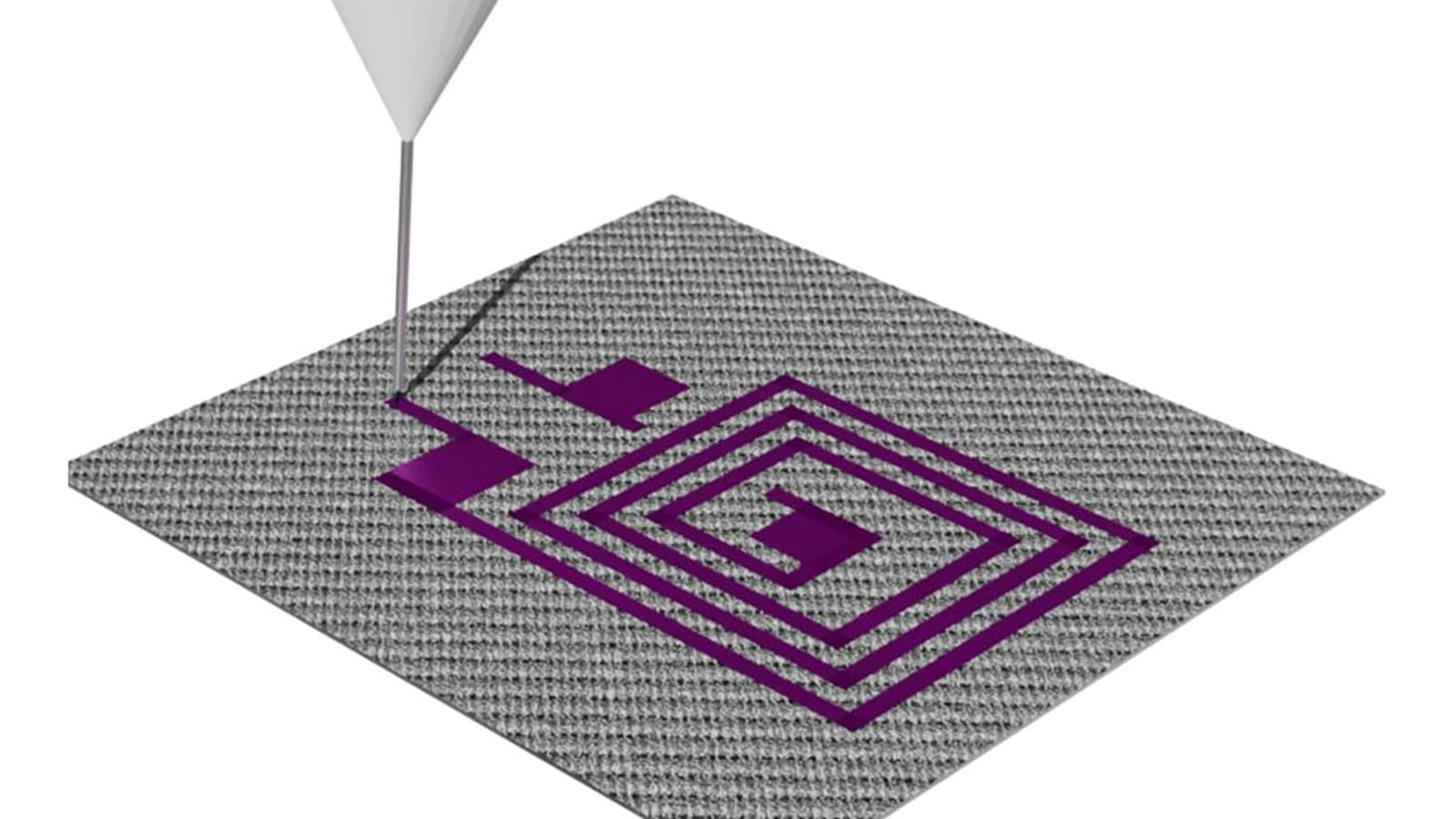

By contrast, the team’s proposed textile grid was printed on a lightweight, flexible cotton substrate the size of a small patch. It includes a printed resonator coil, dubbed an MX-coil, that can convert electromagnetic waves into energy — enabling wireless charging; and a series of three textile supercapacitors — previously developed by Drexel and Accenture Labs — that can store energy and use it to power electronic devices.

The grid was able to wirelessly charge at 3.6 volts — enough to power not only wearable sensors, but also digital circuits in computers, or small devices like wristwatches and calculators. Just 15 minutes of charging produced enough energy to power small devices for more than 90 minutes. And its performance barely diminished after an extensive series of bending and washing cycles to simulate the wear and tear exerted on clothing.

In addition to testing the grid with small electronic devices, collaborators from the University of Pennsylvania, led by Flavia Vitale, Ph.D., an associate professor of neurology, demonstrated that it can also power wireless MXene-based biosensor electrodes — called MXtrodes — that can monitor muscle movement.

“Beyond on-garment applications requiring energy storage, we also demonstrated use cases that may not require energy storage,” said Alex Inman, Ph.D., who helped to perform this research during his internship at Accenture Labs, while a doctoral student and research assistant with Gogotsi in the A.J. Drexel Nanomaterials Institute. “Situations with relatively sedentary users — an infant in a crib, or a patient in a hospital bed — would allow direct power applications, such as continuously wireless powered monitoring of movement and vital signs.”

In this vein, they also used the system to power an off-the-shelf array of temperature and humidity sensors and a microcontroller to broadcast the data they collected in real-time. A wireless charge of 30 minutes powered real-time broadcasts from the sensors — a relatively energy-intensive function — for 13 minutes.

And lastly, the team used the MX-coil to power a printed, on-textile heating element, called a Joule heater, that produced a temperature gain of about 4 degrees Celsius as a proof-of-concept.

“Many different technologies could be powered by wireless charging. The main thing to consider when picking an application is that it needs to make sense for a wearable application,” Gogotsi said. “We tend to think of biological sensors as a very enticing application because this is the future of health care. They can be integrated directly into textiles, increasing the quality and fidelity of the data and increasing user comfort. But our research shows that a textile-based power grid could power any number of peripheral devices: fiber-based LEDs for fashion or job safety, wearable haptics for AR/VR applications like job training and entertainment, and control external electronics when a stand-alone controller may be undesirable.”

The next step for developing this technology involves showing how the system could be scaled up without diminishing its performance or limiting its ability to be integrated into textiles. Gogotsi and Inman anticipate MXene materials holding the key to translating a variety of technology into textile form. Not only can MXene ink be applied to most common textile substrate, but a number of MXene-based devices have also been demonstrated as proofs-of-concept.

“We are producing enough power from the wireless charging to power a lot of different applications, so the next steps come down to integration,” Inman said. “One large way MXene can help with this is that it can be used for many of these functionalities —conductive traces, antennae, and sensors, for example — and you do not have to worry about material mismatches that may cause electrical or mechanical failure.”

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Inman.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing this energy grid?

Inman: Probably tying it to conventional charging. What we had to do was use Qi charging protocols. So, trying to formulate the coil that would work with those off-the-shelf charging profiles. When printing directly onto textile, which has a lot of texture on it, you're limited in some of the things that you can do. So, that was probably technically the most difficult part: trying to get that to all work together.

Tech Briefs: How did this project come about? What was the catalyst for it?

Inman: We had a previous project with the Future Tech labs at Accenture, where we did a larger form factor Maxine Supercapacitor on textile. We were able to power a microcontroller doing temperature sensing and data transmission for 90 minutes. We really proved that out, so the next question was, ‘How do we actually draw power into this thing?' We were using an off-the-shelf DC power supply plugged into the wall and that's not super practical. So, it was really about trying to find more practical ways to integrate the power source into textiles.

Tech Briefs: Can you just explain in simple terms how it works?

Inman: So, basically, the Maxine Coil is a conductive coil we print directly on the fabric, and it acts similarly to a copper coil. You have to tune some of the geometry and make up for differences in conductivity. But, similarly to copper, we can produce an induction charging coil on the textile. But, unlike copper, we can print it directly onto the textile. You can't really do that with copper. So, that's a big advantage of this technology — you can basically print whatever designs you want very quickly and iterate through the process and it all dries at room temperature. You can just think of it as an analog of a copper print, except much easier to do and much more stable on the textile.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any advice for engineers or researchers aiming to bring their ideas to fruition, broadly speaking?

Inman: Fail as much as you can as quickly as you can. You need to have some intuition, but getting through iterations as quickly as possible and learning from your mistakes helps you not repeat those mistakes. So that would be, in general, my advice: Just go out and do it, try to get through stuff. You don't want to be sloppy, but sitting around and not running experiments, not doing stuff rarely helps. I have generally learned much more from a line of mistakes than I would from reading one more paper.