Caltech scientists led by John Dabiri (PhD '05), the Centennial Professor of Aeronautics and Mechanical Engineering, have been taking advantage of the natural ability of jellyfish to traverse and plumb the ocean, outfitting them with electronics and prosthetic "hats" with which the creatures can carry small payloads on their nautical journeys and report their findings back to the surface. These bionic jellyfish must contend with the ebb and flow of the currents they encounter, but the brainless creatures do not make decisions about how best to navigate to a destination, and once they are deployed, they cannot be remotely controlled.

"We know that augmented jellyfish can be great ocean explorers, but they don't have a brain," Dabiri says. "So, one of the things we've been working on is developing what that brain would look like if we were to imbue these systems with the ability to make decisions underwater."

Now Dabiri and his former graduate student Peter Gunnarson (PhD '24), who is now at Brown University, have figured out a way to simplify that decision-making process and help a robot, or potentially an augmented jellyfish, catch a ride on the turbulent vortices created by ocean currents rather than fighting against them. The researchers recently published their findings in the journal PNAS Nexus.

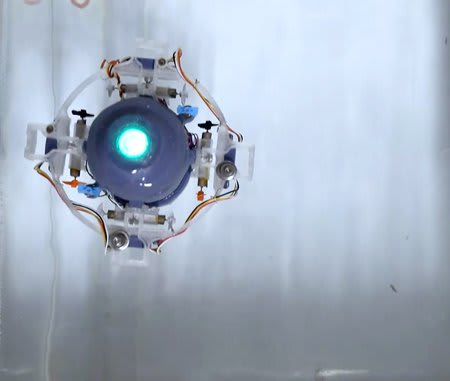

For this work, Gunnarson returned to an old friend in the lab: CARL-Bot (Caltech Autonomous Reinforcement Learning roBot). Gunnarson built the CARL-Bot years ago as part of his work to begin incorporating artificial intelligence into such a bot's navigation technique. But Gunnarson recently figured out a simpler way than AI to have such a system make decisions underwater.

"We were brainstorming ways that underwater vehicles could use turbulent water currents for propulsion and wondered if, instead of them being a problem, they could be an advantage for these smaller vehicles," Gunnarson said.

Gunnarson wanted to understand exactly how a current pushes a robot around. He attached a thruster to the wall of a 16-foot-long tank in Dabiri's lab in the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory on Caltech's campus in order to repeatedly generate what are called vortex rings — basically the underwater equivalents of smoke rings. Vortex rings are a good representation of the types of disturbances an underwater explorer would encounter in the chaotic fluid flow of the ocean.

Gunnarson began using the CARL-Bot's single onboard accelerometer to measure how it was moving and being pushed around by vortex rings. He noticed that every once in a while, the robot would get caught up in a vortex ring and be pushed clear across the tank. He and his colleagues started to wonder if the effect could be done intentionally.

To explore this, the team developed simple commands to help CARL detect a vortex ring's relative location and then position itself to, in Gunnarson's words, "hop on and catch a ride basically for free across the tank." Alternatively, the bot can decide to get out of the way of a vortex ring it does not want to get pushed by it.

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Gunnarson.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while teaching the CARL-Bot to position itself?

Gunnarson: The tricky thing about this kind of problem is that it involves both sensing and decision making. So, in order for this robot to take advantage of the currents we're producing in the tank, it has to both know that the currents are there and then also decide what to do when it's able to sense them. So, I guess the trickiest part was figuring out what kind of signals the robot could sense and then what it could do in response to those specific signals. It was a little bit lucky that I happened to figure out you can swim in a particular direction if you sense a certain signal, and that lets the robot take advantage of currents around it for propulsion.

Tech Briefs: Can you please explain in simple terms how it detects vortex rings and also how it decides whether or not to hold on?

Gunnarson: First of all, I'll say the vortex ring is an experimental analog of a lot of the turbulence that you might find in the ocean and in the atmosphere. It's a very repeatable version that we can use in the lab. It's basically like a smoke ring; what it's doing is using the accelerometer onboard the robot, so the robot can sense that it's being pushed around almost in a little circle by this vertical structure that's coming by. So, if you imagine, there's a tornado passing by, you see things get picked up and spun around by it. It's a similar idea to that. So, once it recognizes that it's being spun around or being pushed around by this vortex ring, that provides enough information to know, okay, the vortex ring is in this direction.

So, if the robot wanted to catch a ride because it was going in the right direction, it could decide ‘Let's swim toward this tornado of fluid.’ But equally, if this structure was going the wrong way, the robot could decide, ‘Oh, I wanna swim in the opposite direction to not get caught up in it.’ It's this sort of decision-making that you would put into a future vehicle that would hopefully decide to ride with currents or avoid them depending on where you want it to go.

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you'd like to add that I didn't touch upon?

Gunnarson: It's an exciting area of research because engineers typically look at traditional vehicles like airliners and are excited for like a 1 percent improvement in that efficiency. But, when we're talking about these smaller autonomous vehicles, the potential gains that you can get by interacting more intelligently with currents and gusts can be huge. So, I think, it's a new area of research that's kind of spurred on by these small autonomous systems that I think will have really big gains in the future.

Transcript

No transcript is available for this video.