Load management is the most consequential to the success of electric vehicle (EV) fleet implementation. Without sophisticated systems to ease the impact of EV charging on the distribution grid at scale, the transition to EVs will be impeded by the cost and time requirements of electrical infrastructure upgrades. This article introduces the fundamental concepts behind EV load management, which allows fleet operators to fit more EV chargers on the utility service that they currently have. At the core of this approach is a hybrid local-plus-cloud charge management architecture designed to unlock a hierarchy of load management capabilities, ranging from a single site to distribution grid-level impact.

The Challenge

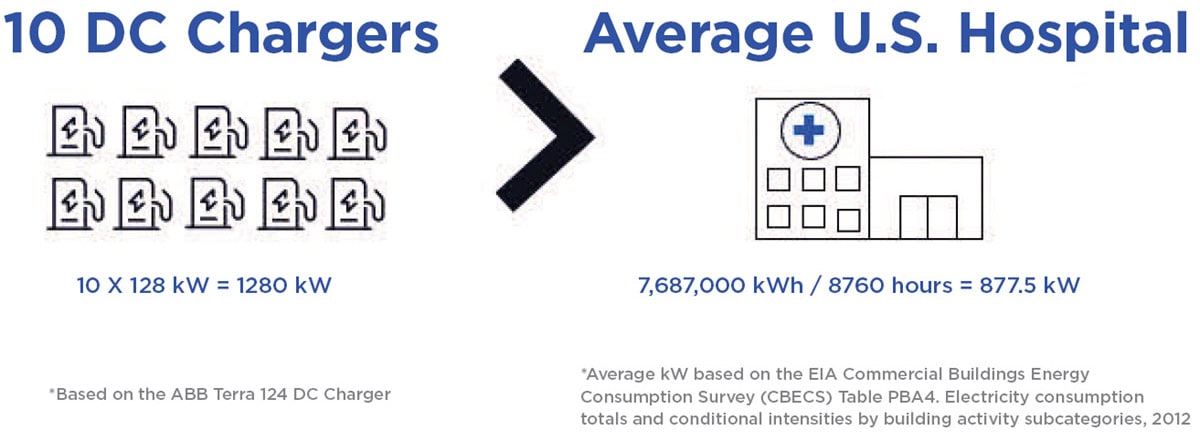

Fleets such as school districts, transit agencies, and commercial delivery operations have been enthusiastic early adopters of EVs. EV fleet load growth is densely concentrated as fleets often park their vehicles together in depots or parking lots, charging on a single utility interconnection. Electrical equipment must be sized to handle the maximum load at any one location, and a few concentrated loads in a neighborhood can quickly max out a transformer or substation. The procurement and design of higher-capacity equipment to handle this densely concentrated load can be prohibitively expensive and can add months or years to a project. Without EV load management, fleet electrification is severely impeded by electrical capacity constraints in most areas (Figure 1).

Fundamentals of Reliable EV Load Management

Reliable charging and responsive control of EV chargers is the key responsibility of a charge management system (CMS). In the case of upgrade avoidance, a failure could be seriously destructive, as an overloaded panel could result in an arc flash or fire hazard. This robust reliability is accomplished by housing charging logic and optimization directly on a local control device for the lowest latency and fastest optimization. Some CMSs offer cloud-based load management without local control. In our experience, this is insufficient for most advanced use cases including upgrade avoidance.

The system must also be multi-functional, designed not only to walk and chew gum at the same time but also must be able to do the electrical equivalent of walking, chewing gum, spinning plates and debating Shakespeare. Like a thousand-year-old pyramid built from thousands of blocks, a reliable CMS is crafted from thousands of lines of code, designed on solid principles, and tested across countless sites.

Even the best system must be built with safety mechanisms in place for when things go wrong. This is achieved with fallback values assigned to each individual charger and meter, stored on the CMS’s non-volatile memory and on the chargers’ non-volatile memory. These points act as a calculated upper safe assumption to which both the charger and CMS can default when connection or control problems arise.

Finally, the CMS functions as the nerve center of an integrated system. The reliability of the system relies on strong communication and collaboration with quality technology and design partners for integrations and engineering. Open standards, such as Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP) for communications between the CMS and the charging stations, and Modbus for communication with energy management systems, are critical.

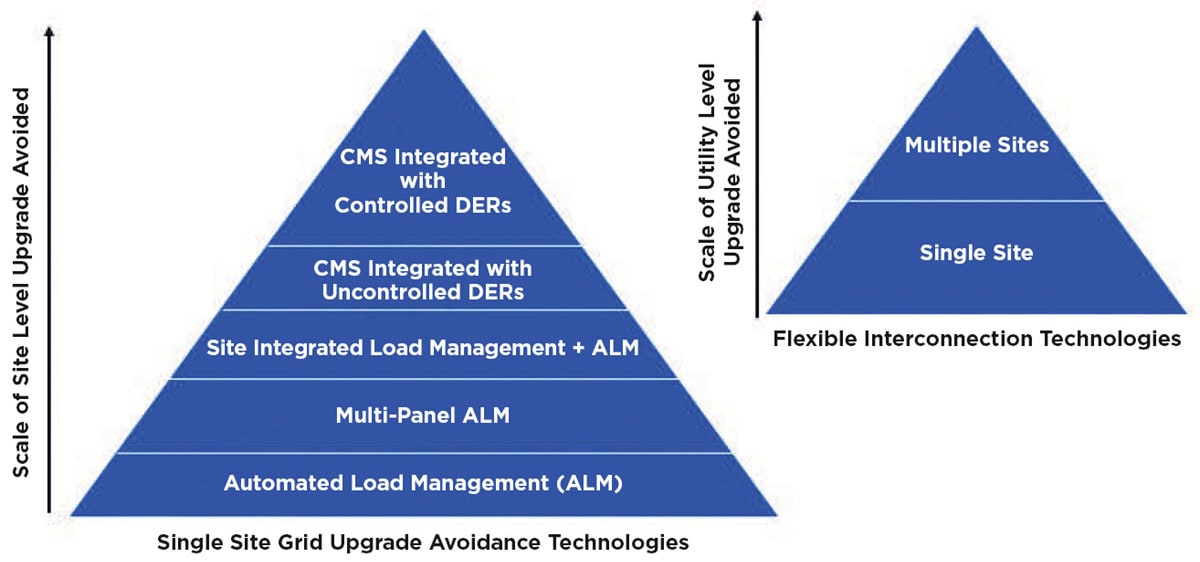

The Pyramid of Load Management CMS Technology

Building on this foundation, the CMS can now accomplish increasingly complex levels of load management to facilitate upgrade avoidance. For fleets that need to deploy faster and more cost-efficiently, using existing power infrastructure, there is a hierarchy of load management CMS use cases to consider (Figure 2).

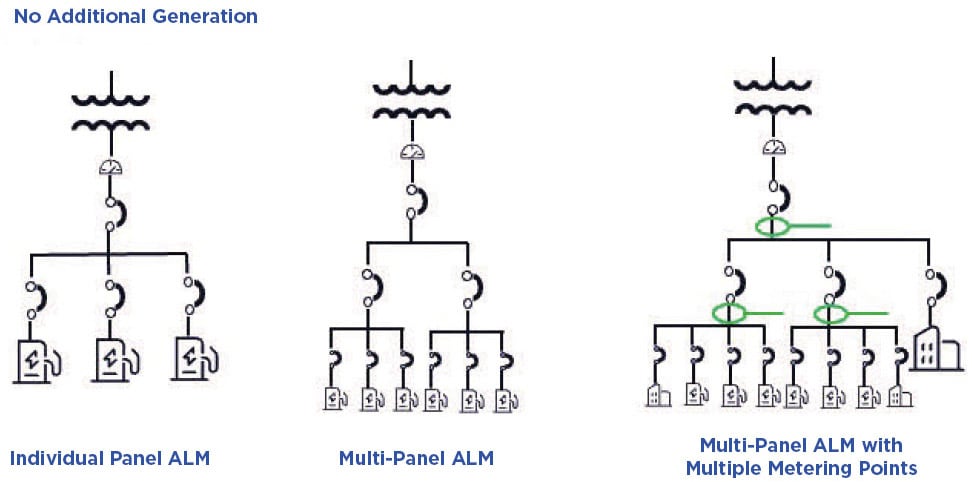

The most basic grid upgrade avoidance use case for EV fleets is automated load management (ALM) at a single panel level, whereby the CMS controls the power usage of multiple EV chargers so that their total power usage does not exceed a single threshold. This threshold is determined by the smallest of the associated panel, breaker and conductor ratings of that panel.

ALM is a transformational technology, changing how EV infrastructure is treated in the National Electrical Code, and currently in commercial operation in transit and school bus projects in California and New York. A school bus operator in New York was able to use automated load management to safely install 17 chargers on a site that theoretically would only have capacity for seven without ALM.

The next level of load management is the ability to control EV load across multiple electrical panels while respecting all controlling equations. For example, in its simplest form, a site might have two subpanels with a group of EV chargers on each, feeding into a main service panel and connected to a single interconnection. In this case, the CMS must be able to solve a system of three equations, one per panel. The CMS must be able to process all equations at once, limiting charging load to each subpanel’s capabilities, and continuously respecting the main panel’s limit ( Figure 3).

One level up is the ability to meter across multiple panels with uncontrolled loads. This is known as site-integrated load management (SILM). SILM allows the fleet and facility operators to use any available energy that isn’t being used to power buildings or other non-EV equipment for managed EV charging, in real-time. Taking the hypothetical site above, SILM makes it possible to add a meter to each of the panels to monitor the unused power of an HVAC system on the main panel, lighting load on the first subpanel and a bus wash on the other subpanel. When any of these loads are below maximum capacity, more power can be made available to the EV chargers using SILM.

Without these meters, the CMS would be required to reserve the maximum power capacity for each of these systems at all times and use none for EV charging. The system of equations now includes two types of dynamically changing variables: the EV charging power under CMS control, and monitored but uncontrolled variables, i.e. HVAC, lights, and bus wash.

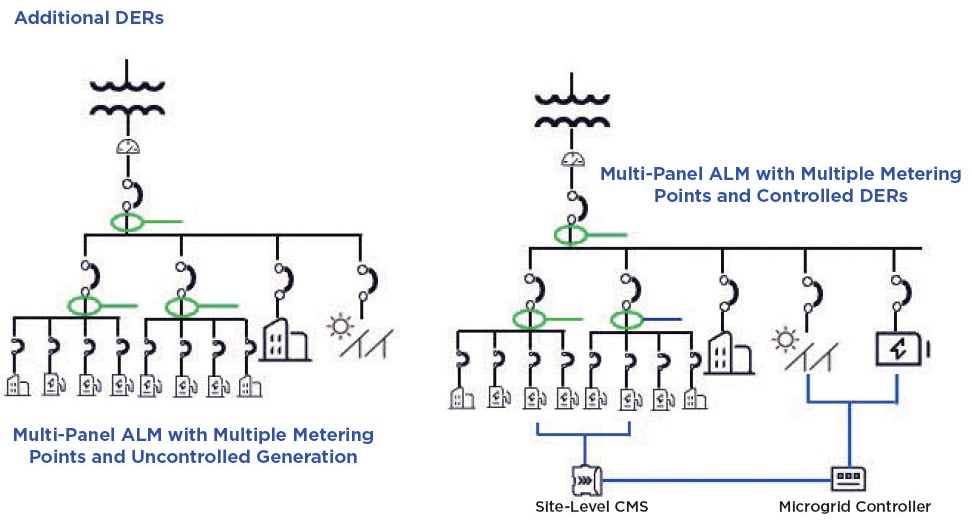

For fleets at power-constrained sites, there may come a point at which the load management options previously described cannot service the entire fleet’s charging needs, and the operator may consider adding on-site energy generation. In those cases, the CMS can integrate with uncontrolled or controlled distributed energy resources (DERs), such as solar, stationary storage, or a backup generator to add local power supply to avoid total reliance on grid power.

For sites with small to medium additional power needs, uncontrolled DERs like solar may be sufficient, with the CMS only required to monitor and respond to these sources. However, at some of the largest sites, fleets may need to combine ALM with DERs that are controlled and co-optimized along with the charging. This is the capstone of the grid upgrade avoidance pyramid. For this function, the CMS will need to communicate with a microgrid controller using local open communication standards such as Modbus (Figure 4).

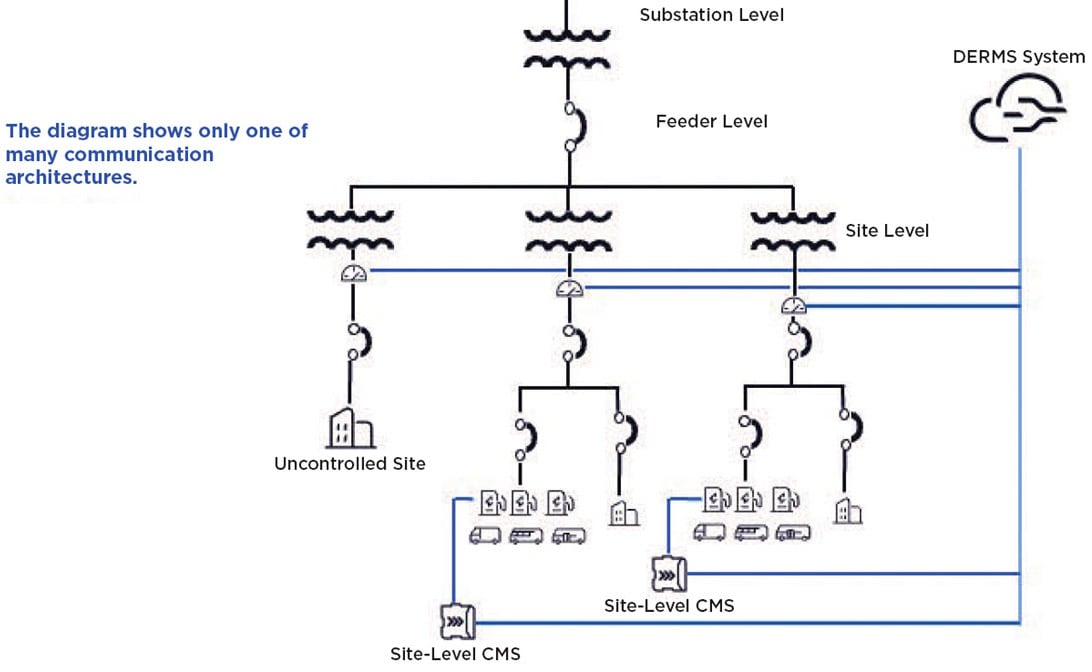

Flexible Interconnections

When one or more sites within a distribution line are managing EV load precisely and effectively with a reliable CMS, as described above, this creates an opportunity for grid operators to address grid constraints at a substation level using flexible interconnections. By building on the CMS’ reliable and resilient EV load management capabilities at a site-level, the network effects of this control can be leveraged to avoid larger scale infrastructure upgrades at substation levels and participate in other grid stability functions such as demand response events. Currently, utilities across the country are starting to develop pilot programs and regulations employing these controllable connections (Figure 5).

Conclusion

Controllable load at scale is an important tool for utilities and fleet operators that unlocks tremendous value and enables faster and cheaper energization of EV fleets. For a smart grid to be possible, it must be built on the foundation of scalable and proven technology. Every block at the base of the upgrade avoidance pyramid must be built upon absolute trust and confidence that load management will be 100 percent effective and reliable to allow for superior site level upgrade avoidance. This site-level control can then be leveraged to get utility level upgrade avoidance to make optimal use of the grid while investing efficiently in the grid of the future.

This reliability, flexibility, and control unlocks more than just intelligence. It is the roadmap to the largest problem faced by the grid on the path to a cleaner planet.

This article was written by Elizabeth Hughes, Sales and Applications Engineer, The Mobility House North America (Belmont, CA). For more information, visit here .