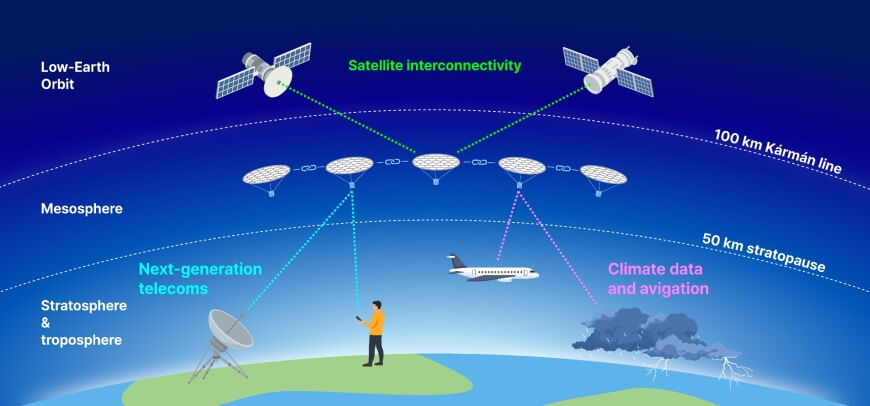

Between 50 and 100 kilometers (30-60 miles) above Earth’s surface lies a largely unstudied stretch of the atmosphere, called the mesosphere. It’s too high for airplanes and weather balloons, too low for satellites, and nearly impossible to monitor with existing technology. But understanding this layer of the atmosphere could improve the accuracy of weather forecasts and climate models.

A new study published in Nature by researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), University of Chicago, and others introduces a novel way to reach this unexplored near-space zone: lightweight flying structures that can float using nothing but sunlight.

“We are studying this strange physics mechanism called photophoresis and its ability to levitate very lightweight objects when you shine light on them,” said Lead Author Ben Schafer, former Harvard graduate student in the research groups of Joost Vlassak, the Abbott and James Lawrence Professor of Materials Engineering at SEAS, and David Keith, now a professor at the University of Chicago.

Photophoresis occurs when gas molecules bounce more forcefully off the warm side of an object than the cool side, creating continuous momentum and lift. This effect only happens in extreme low-pressure environments, which are exactly the conditions found in the mesosphere.

The researchers built thin, centimeter-scale membranes from ceramic alumina, with a layer of chromium on the bottom to absorb sunlight. When light hits this structure, the heat difference between the top and bottom surfaces initiates a photophoretic lifting force, which exceeds the structure’s weight.

“This phenomenon is usually so weak relative to the size and weight of the object it’s acting on that we usually don’t notice it,” Schafer said. “However, we are able to make our structures so lightweight that the photophoretic force is bigger than their weight, so they fly.

The concept originated more than a decade ago when Keith hypothesized different uses of photophoretic particles, including their potential to reduce climate warming. A collaboration began with then-graduate student Schafer, and Vlassak, an expert in nanofabrication and experimental mechanics, in order to help move the concepts from theory to reality.

The collaboration became feasible through recent advances in nanofabrication technology, which allow researchers to build low-mass, nanoscale devices with greater precision.

“We developed a nanofabrication process that can be scaled to tens of centimeters,” Vlassak said. “These devices are quite resilient and have unusual mechanical behavior for sandwich structures. We are currently working on methods to incorporate functional payloads into the devices.”

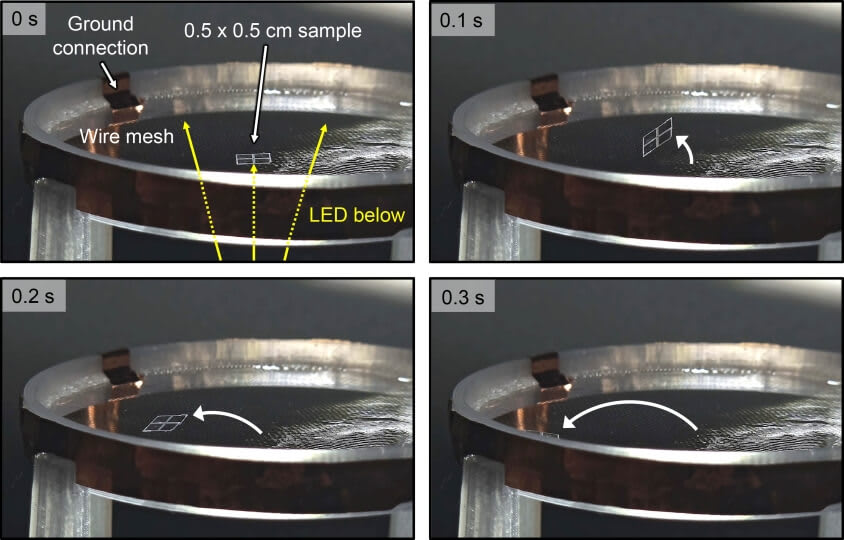

Using these fabrication methods, the research team created centimeter-scale structures and directly measured the photophoretic forces acting on them inside a low-pressure chamber Schafer and former Harvard postdoctoral fellow Jong-hyoung Kim built in Vlassak’s lab. They compared those results to predictions of how such structures would behave in the upper atmosphere. Device design and fabrication were led by Kim, who is now a professor at Pukyong National University in South Korea.

“This paper is both theoretical and experimental in the sense that we reimagined how this force is calculated on real devices and then validated those forces by applying measurements to real-world conditions,” Schafer said.

A key experiment detailed in the paper shows a one-centimeter-wide structure levitating at an air pressure of 26.7 Pascals when exposed to light at just 55 percent the intensity of sunlight. This pressure condition models what’s found 60 kilometers above the Earth’s surface.

“This is the first time anyone has shown that you can build larger photophoretic structures and actually make them fly in the atmosphere,” said Keith. “It opens up an entirely new class of device: one that’s passive, sunlight-powered, and uniquely suited to explore our upper atmosphere. Later they might fly on Mars or other planets.”

Here is an exclusive Tech Briefs interview, edited for length and clarity, with Schafer.

Tech Briefs: What was the biggest technical challenge you faced while developing these lightweight nanofabricated structures? And getting them to passively float via photophoresis?

Schafer: We faced two big challenges: modeling the forces on the structures and finding the best way to measure those forces in the lab. The modeling could not be done analytically, since it’s difficult to precisely quantify the gas-structure interactions when the size of the structure is around the average distance between gas molecules (i.e. the mean free path). Thankfully, Felix Sharipov (our co-author) led numerical simulations of the gas molecules at different pressures, which solved this issue for us.

Measuring the forces was difficult because we’re talking about trying to detect micro-Newtons of force in a vacuum system while illuminating these structures at the same time. We eventually found a solution: we glued test samples to a very sensitive scale and used a laser to simulate the sun. By toggling the laser off and on, we measured the change in weight (proportional to the lofting force) on the structure when the laser was on. This simulated the conditions of the mesosphere and helped to validate the model.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any set plans for further research/work/etc.? If not, what are your next steps?

Schafer: There are two tracks for future research. First, at Harvard, we’re working toward integrating useful payloads onboard these devices, and have already come up with some novel ways to hang structures below the devices, as described in the paper. Second, at my company (Rarefied Technologies), we’re aiming to demonstrate photophoretic flight of similar structures in the atmosphere next year. [Just to note: Rarefied was not involved in the Nature paper but did spin out of Harvard last year, and we are developing the same devices.]

Tech Briefs: Is there anything else you’d like to add that I didn’t touch upon?

Schafer: It’s pretty neat that this piece of physics, regarded as a novelty for so long, has real world applicability, especially in a region of the atmosphere that is so understudied.

Tech Briefs: Do you have any advice for researchers aiming to bring their ideas to fruition?

Schafer: Get out of the lab and talk to as many people as you can about what you’re doing, especially if you’re working on an applied project. It’s amazing to learn about the ways in which your tech might help others in ways you haven’t thought of!