Traditionally, measuring heart rate requires some sort of wearable device, whether that be a smart watch or hospital-grade machinery. But new research from engineers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, shows how the signal from a household Wi-Fi device can be used for this crucial health monitoring with state-of-the-art accuracy — without the need for a wearable.

Their proof-of-concept work demonstrates that one day, anyone could take advantage of this non-intrusive Wi-Fi-based health monitoring technology in their homes. The team proved their technique works with low-cost devices, demonstrating its usefulness for low resource settings.

A study demonstrating the technology, which the researchers have coined “Pulse-Fi,” was published in the proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT).

A team of researchers at UC Santa Cruz’s Baskin School of Engineering that included Professor of Computer Science and Engineering Katia Obraczka, Ph.D. student Nayan Bhatia, and high school student and visiting researcher Pranay Kocheta, designed a system for accurately measuring heart rate that combines low-cost Wi-Fi devices with a machine learning algorithm.

Wi-Fi devices push out radio frequency waves into physical space around them toward a receiving device, typically a computer or phone. As the waves pass through objects in space, some of the wave is absorbed into those objects, causing mathematically detectable changes.

Pulse-Fi uses a Wi-Fi transmitter and receiver, which runs Pulse-Fi’s signal processing and machine learning algorithm. The researchers trained the algorithm to distinguish even the faintest variations in the signal caused by a human heartbeat by filtering out all other changes to the signal in the environment or those that are caused by activity like movement. “The signal is very sensitive to the environment, so we have to select the right filters to remove all the unnecessary noise,” Bhatia said.

The team ran experiments with 118 participants and found that after only five seconds of signal processing, they could measure heart rate with clinical-level accuracy. At five seconds of monitoring, they saw only half a beat-per-minute of error, while longer periods of monitoring time increased the accuracy. The team found that the Pulse-Fi system worked regardless of the position of the equipment in the room or the person whose heart rate was being measured — no matter if they were sitting, standing, lying down, or walking. For each of the 118 participants, they tested 17 different body positions with accurate results.

These results were obtained using ultra-low-cost ESP32 chips, which retail between five and 10 dollars and Raspberry Pi chips, which cost closer to 30 dollars. Results from the Raspberry Pi experiments show even better performance. More expensive Wi-Fi devices like those found in commercial routers would likely further improve the accuracy of the system.

They found that their system had accurate performance with a person three meters, or nearly 10 feet, away from the hardware. Further testing beyond what is published in the current study shows promising results for longer distances. “What we found was that because of the machine learning model, that distance apart basically had no effect on performance, which was a very big struggle for past models,” Kocheta said.

To make their heart rate detection system work, the researchers needed to train their machine learning algorithm to distinguish the faint detections in Wi-Fi signals caused by a human heartbeat. They found that there was no existing data for these patterns using an ESP32 device, so they set out to create their own dataset.

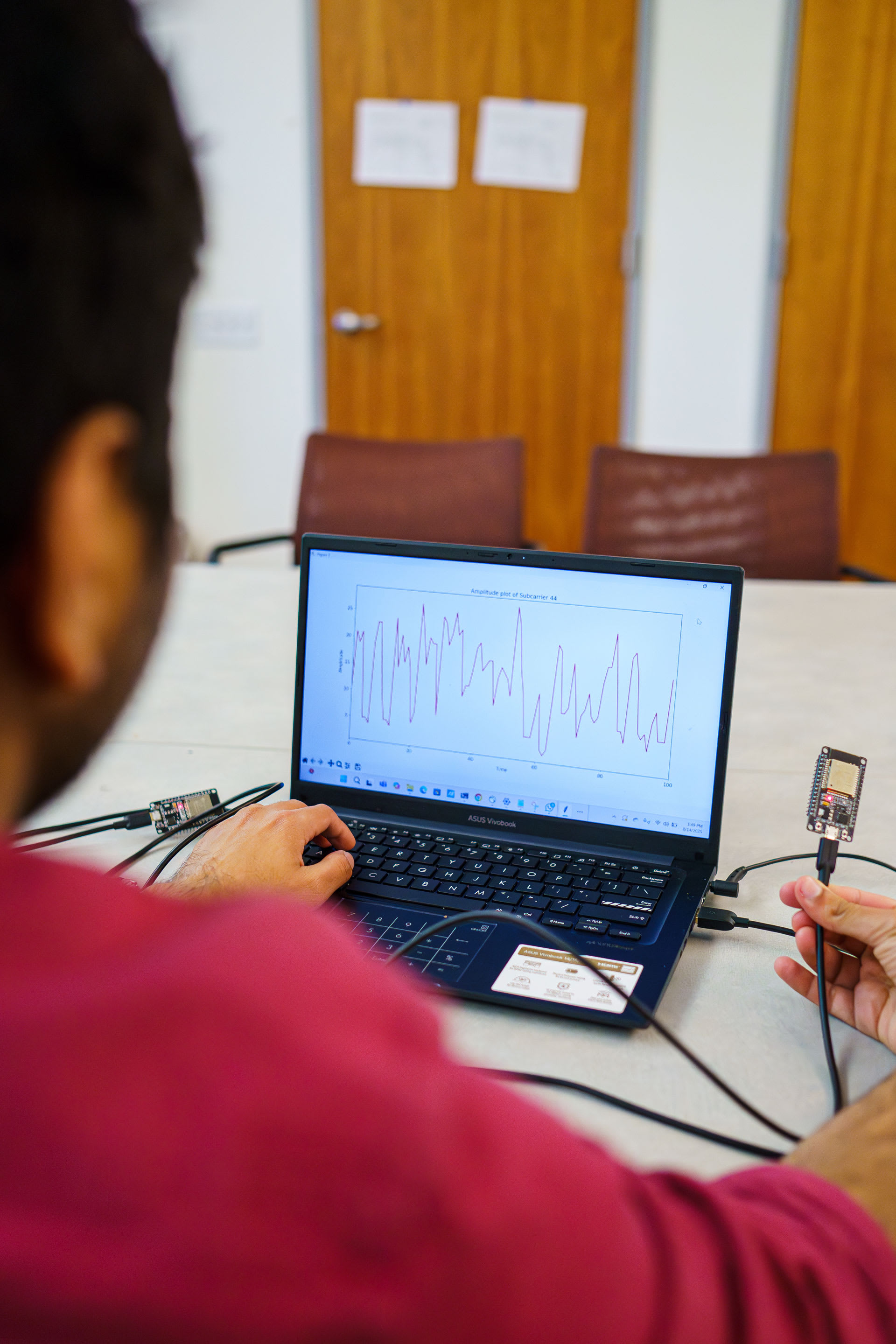

In the UC Santa Cruz Science and Engineering library, they set up their ESP32 system along with a standard oximeter to gather “ground truth” data. By combining the data from the Pulse-Fi setup with the ground truth data, they could teach a neural network which changes in signals corresponded with heart rate.

In addition to the ESP32 dataset they collected, they also tested Pulse-Fi using a dataset produced by a team of researchers in Brazil using a Raspberry Pi device, which as far as the researchers are aware, is the most extensive existing dataset on Wi-Fi for heart monitoring.

Now, the researchers are working on further research to extend their technique to detect breathing rate in addition to heart rate, which can be useful for the detection of conditions like sleep apnea. Unpublished results show high promise for accurate breathing rate and apnea detection.