Everywhere we look we are bombarded with 3D. It’s in movies, in-home entertainment, digital camcorders, gaming systems, laptops, and even in our labs. What is it about 3D that is so fascinating and what are some of the technology drivers that are determining its future?

While all of these provided some sense of dimensionality, fun effects, and entertainment, none provided a genuinely immersive or realistic environment. Today there is a convergence of technologies that is making 3D more readily acceptable and affordable, not just for the mainstream consumer market but for research, surveillance, inspection, process control, and a wide variety of medical applications.

Perception vs Reality

Three critical components are required to simulate 3D: content creation, processing, and display. Each plays a role in helping us recreate what our own eyes and brain do naturally. Achieving the highest level of realism involves a combination of technologies working together and delivered at a cost point which is viable for the intended application. It is true that 3D images can be completely synthesized within a software environment for research tools, computerized design platforms, and entertainment. This article, however, will discuss capturing images stereoscopically using video cameras to produce content.

In the United States, the Advanced Television Systems Committee (ATSC) defines several HD and standard definition formats for broadcasters. The most common HD format for cable and broadcasters is 720p which corresponds to 1024 x 720 progressive. When 3D content is broadcast by cable and satellite, the resolution is reduced by half to 1920 x 540, or 540p, to transmit the left and right views within the HD broadcast signal. Alternatively, Blu-ray Disc™ players are capable of delivering 3D content in full resolution 1920 x 1080 format.

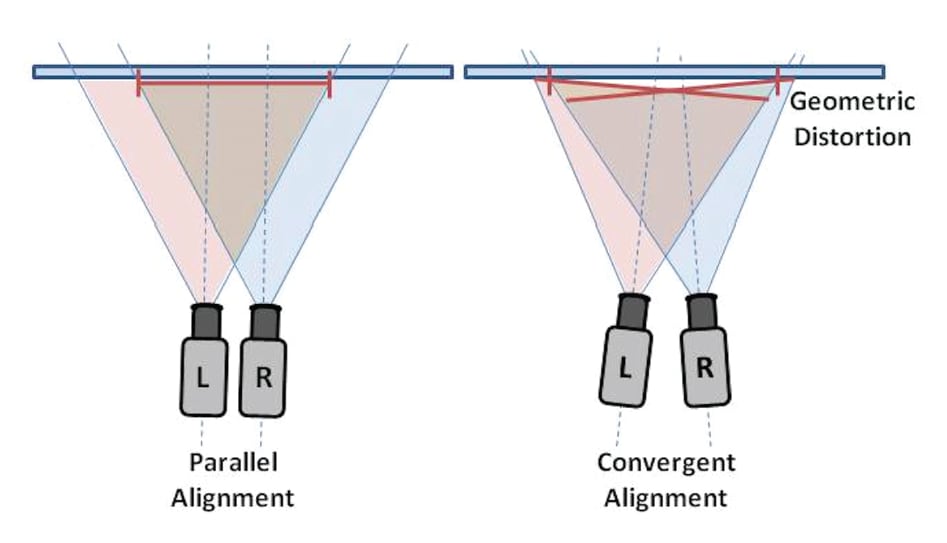

Camera Alignment

The convergence angle in combination with the intraocular distance during filming can have a significant impact on the amount of 3D effect. As the convergence angle increases, in combination with intraocular distance, the 3D effect will be more extreme. Too much convergence, however, could result in geometric distortion which may prove difficult to correct in postprocessing, if required.

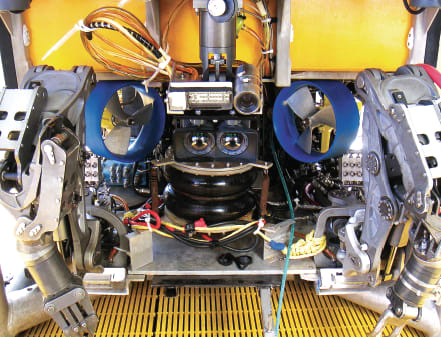

3D camera rigs include a number of different formats including side-by-side (Figure 3) and beamsplitter configurations (Figure 4). Side-by-side would seem to be the most natural method to recreate the positioning of our eyes. However, due to lenses, optics, and the distances between the cameras and the target object it may be impossible to bring the two cameras close enough together using only a side-by-side arrangement.

In a beamsplitter rig, the cameras are mounted on different planes, perpendicular to one another with a 50/50 mirror at 45° to each camera. These rigs allow the two cameras to be placed in a wide range of positions relative to each other to accommodate any situation — from fully superimposed to several inches of separation. In both of these configurations, if the lenses are zoomed into the shot, the cameras are synchronized to pull closer together to maintain the appropriate alignment as the relationship and distances to the target object change.

Processing is required to properly format stereoscopic images so they can be presented in a way that reveals the 3D effect. The formats will depend on the playback method and could include anaglyph, left/right side-by-side, or top and bottom. In some instances, two separate video files are sent through a multiplexer or MUX box which formats the two independent signals into a viewable 3D composite signal. Blu-ray Disc players will automatically output the content in an appropriate 3D format as required by your display. There are also a number of software tools to convert 2D images into 3D content.

Display technology has a huge impact on viewing 3D images and although beyond the scope of this article, a few comments on this critical component are appropriate. There are significant differences in technologies and standards used between home systems and movie theaters. 3D digital cinema depends on a Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) compliant projector(s) operating at up to 4K video matrix and 48 frames per second (fps), polarizing filters, and special reflective screens which can be viewed using inexpensive passive-polarized glasses. At home, most 3D displays use active-shutter technology requiring expensive LCD glasses which are RFlinked to the TV, switching each eye on and off up to 120 times per second in synchronization with the monitor. In this way full HD content can be displayed. Passive glass technology for home use cuts resolution in half. Future enhancements will improve HD resolution by implementing new active screen technology that retains full HD display while permitting the use of passive technology glasses. Glasses-less, autostereoscopic technology is becoming available, but currently is most successfully implemented on smaller displays such as the view finder on 3D camcorders, portable gaming terminals, and laptops. Large format autostereoscopic displays have been introduced to mixed reviews due to the presence of 3D viewing zones and reduced resolution compared to other 3D display technology.

Applications

Beyond entertainment, 3D has practical implementation in various applications including surgical imaging (Figure 5), remotely controlled underwater inspection systems (Figure 6), surgical microscopy, industrial inspection, and process control. There are several commercially-available, FDAapproved, stereoscopic video systems for surgery. Applying 3D in surgery offers surgeons improved depth perception which is important given the increasing use of minimally invasive and single-port surgical techniques. With these procedures, the surgical field-of-view is narrowed, making it more challenging to discern depth and the orientations of medical instruments and anatomical structures. While the addition of stereoscopic imaging helps physicians improve their visualization, it remains dependent on the surgeon’s experience and training to produce the full benefits of these technologies.

What is in store for the future? The latest wave of 3D, since the theatrical release of James Cameron’s Avatar in 2009, seems to be in its infancy. We understand how to capture 3D content and with new schemes emerging we can convert single camera 2D into 3D. With further advancements in processing and new display technologies which eliminate glasses, 3D will not be just an option, but will quickly become a standard part of our entertainment and visual media environment.

This article was written by Paul Dempster, Director of Sales & Marketing, Toshiba Imaging Systems Division (Irvine, CA). For more information, contact Mr. Dempster at