At Cox Automotive’s EV Battery Solutions center in Oklahoma City, the conglomerate most famous for its KBB, Autotrader, and Manheim auction brands, has become a go-to for EV battery research, repair, remanufacturing, and recycling.

It’s something that not a lot of EV buyers think of. When the complex, virtually living organisms that power EVs have problems, it’s often not a simple fix that can be handled by a dealer’s traditional service technicians. Enter Cox, whose “Flying Doctors” can be dispatched to either complete the repair or walk the dealer’s technicians through the process.

And if the problem is more extensive, a dealer and OEM can send a battery to Oklahoma City, where separate diagnostic and service teams work on the problem. If the battery can’t be saved, it is sent to another end of the compound to be recycled and turned into scrap and black mass that can be used again. As we’ll see below, the EV battery recycling space is growing.

Lea Malloy, Cox AVP for EV battery solutions, said the 11-year-old business, which was Spiers New Technologies before Cox acquired it in 2021, “is the first and only one-stop shop for the entire battery lifecycle.”

Malloy is particularly proud that the company “supported the nation’s largest battery recall,” the fire-related recall of 2017 to 2022 Chevy Bolt and Bolt EUV models. “We learned a lot from that.”

Though the Oklahoma City center is Cox’s largest, they also exist in Detroit, Las Vegas, and Atlanta, near the company’s headquarters. One unique advantage for the company when shipping batteries to and from repair centers is that it can use Mannheim Auctions’ already-existing transportation network that operates between its 145 locations.

Home-Cooked Diagnostics

“Battery diagnostics is our special sauce,” Malloy said, referring to the electronics lab, which researches batteries and determines best diagnostic practices. Connor Taylor, the lab’s Engineering Manager, discussed how the lab has a startup mentality when it comes to engineering and building their own diagnostic tools.

“The testing we need to do with some of these batteries, sometimes there just isn’t a commercial option, so we have to build the equipment,” he said. “An example of that is this 800-volt isolated voltage acquisition part. Some newer batteries are 800-volt architecture or higher, and most of the commercial equipment tops out at 600 volts. So, we couldn’t really find anything that would fit our needs. So, we had to roll our own.”

He said the other big category of self-built equipment is things that do exist, but there’s a reason for building it in-house. Often, that’s cost. He showed a source measurement unit for testing Toyota Prius and Camry battery modules. Testing involves repeatedly charging and discharging cells while recording voltage, current and temperature. “You can buy off-the-shelf equipment that does that,” Taylor said. “But we calculated that we needed 2,000 channels and were quoted $1,000 a channel. Back in 2018 we didn’t have $2 million to just give to a supplier and wait nine months.”

Cox had a completed design in 2019 but then the chip shortage hit and forced them to design the unit a second time. “That was somewhat of a good thing,” he said, because it allowed them to use newer, better chips. The end cost of the project: A mere $20,000.

Among other tools developed in-house is a 25kW rapid discharger used by the recycling crew to deplete batteries before they’re shredded.

Other Recyclers

Inventing tools is just part of the work when it comes to developing EV battery recycling technologies. One company that apparently has enough solutions developed to attract OEM partnerships is Redwood Materials, which currently operates a campus in Reno, NV, where it recycles, refines, and manufactures battery components.

Redwood Materials, founded by former Tesla Co-Founder JB Straubel, recycles and refines old, broken batteries into new manufactured components in Reno, NV. It is building a second campus in Charleston, SC, not far from BMW Group’s EV-focused Plant Spartanburg and Plant Woodruff. In September, BMW announced that it would work with Redwood to recover end-of-life lithium-ion batteries from BMW’s close-to-700 locations — like dealerships and distribution centers — in the U.S. Denise Melville, BMW’s Head of Sustainability, said in a statement that with the Redwood deal, BMW “is laying the groundwork for the creation of a fully circular battery supply chain in the U.S.”

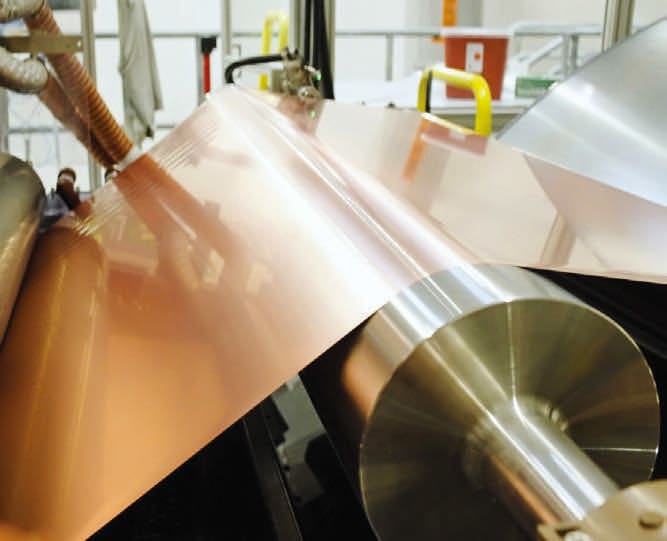

BMW was beaten to the punch by VW, Audi, Toyota, and Ultium, which have all announced some sort of battery recycling deal with Redwood in the last two years. Toyota, for example, announced in November 2023 that it would source cathode active material (CAM) and anode copper foil from Redwood’s recycling processes for use in future hybrids and EVs. Toyota will use the recycled material at the new $14-billion Toyota Battery Manufacturing plant in North Carolina when it opens in 2025.

Ultim said in early 2024 that it would send production scrap materials — cell scrap, cathode, and anode material — from its Warren, OH, and Spring Hill, TN, battery facilities to Redwood. Ultium said in a statement that “despite tremendously efficient production rates, cell manufacturing still experiences a 5-10 percent scrap rate on average,” a number that translates to around 10,000 tons of material each year. VW and Audi, while also talking with Redwood about EV battery recycling, encouraged customers to bring in old batteries and devices so Redwood could extract the lithium from them.

94% Material Recovery

For Cox, it’s about a three-day recycling process to ensure battery discharge, then run everything through various shredders. Powerful air separators divide big pieces from smaller pieces, then actual shredders tear the cells and contents apart. At each stage, material is separated into its component parts until eventually part of it is the black mass containing anode and cathode materials that can be resold. According to Cox, it produces the best, least-contaminated black mass on the market, and the claim is backed by partner Aleon Metals.

Tim Harris, Director of Operations Management at Cox, said it’s because of the unique, dry recycling process. “Our black mass is shredded in a dry process. We don’t push them down into water to shred them, so we depower [the batteries] to zero before we shred,” he said. “Some other companies run it through a water solution so they can shred live modules. We depower them so they’re safe before we shred them. He also said that process is environmentally cleaner.

“It’s traveling up one conveyor. From that point, it moves on to several crushing pieces. When we go to crush it, get it to that particular size we need. We also have a series of separators that actually break down these particular sizes [and] get to what we need to get that really clean black mass,” added Harris.

Being cleaner is a relative term in battery recycling, though, and it takes effort and consistency to successfully protect workers and the surrounding area. Cox’s enormous recycling room had a gray haze floating in it when SAE Media visited. Thirty-two recycling techs, operating in two shifts, work in fully encapsulated suits and what look like 3M Versaflo air-supply helmets. As for protecting the outside world, exhaust air goes through a series of filters before leaving the building.

The recycling center handles up to 2,000 modules a day, but workers said in a more typical day they process about 1,000.

This article was written by Chris Clonts, Editor, SAE Media Group. Sebastian Blanco, Editor-in-Chief, Automotive Engineering also contributed to this article.